BOGAN SVATOŠ

When he was just about to turn forty, he knew that the greatest adventure of his life was still ahead of him. Sandstone climber and a mountaineer Bogan Svatoš, leader of the first Czechoslovak Himalayan expedition

DREAM AND MATTER

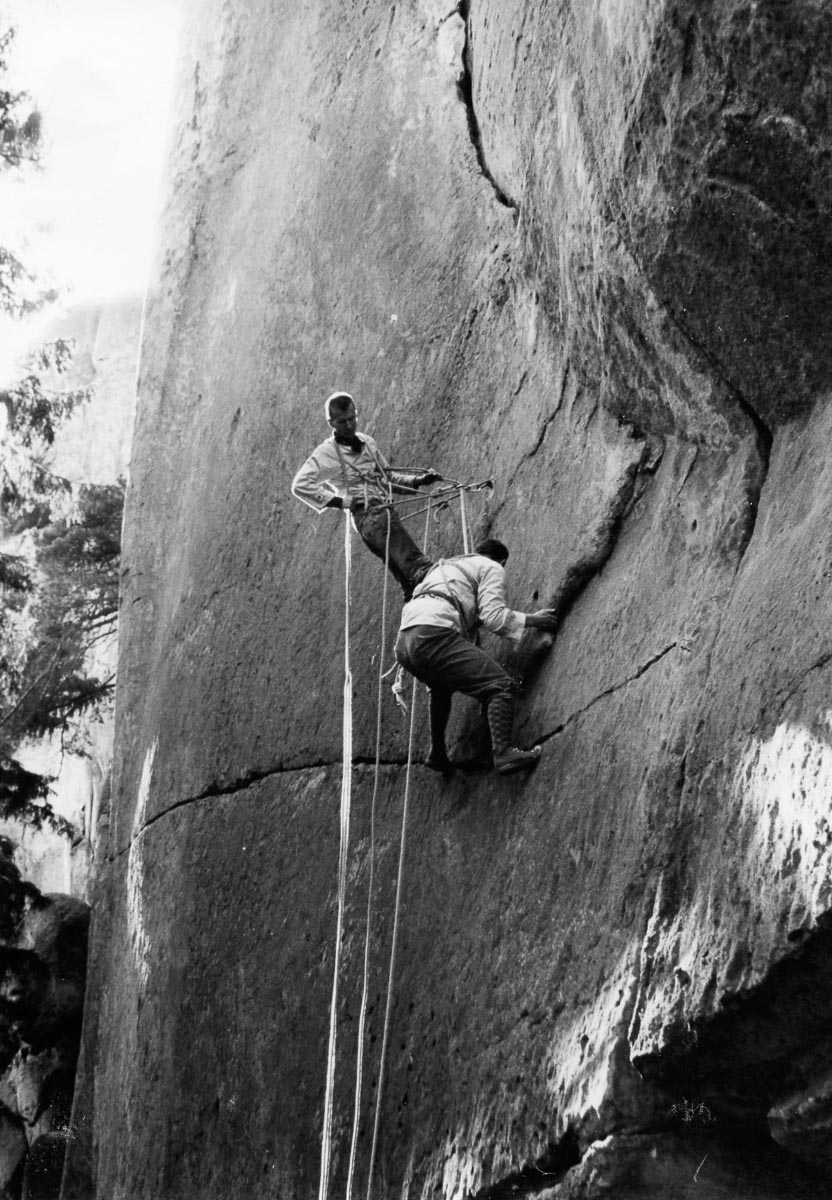

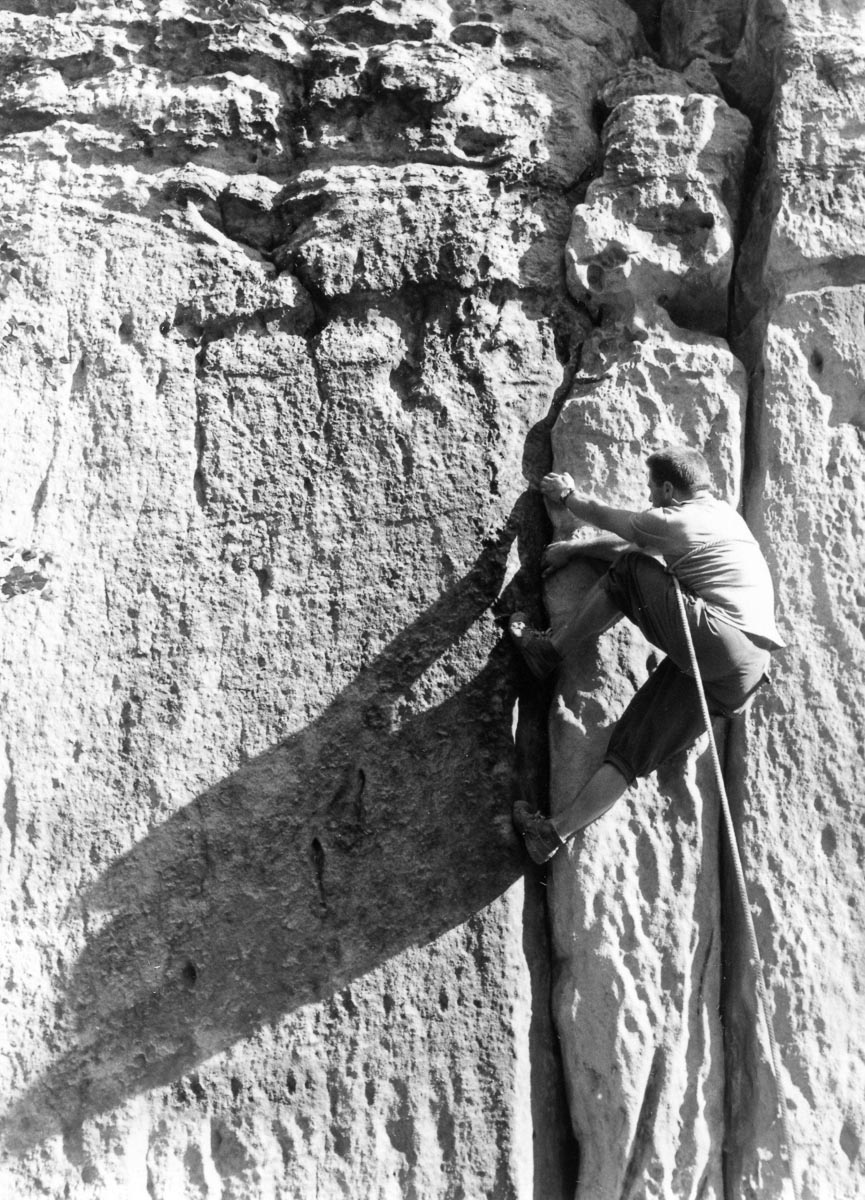

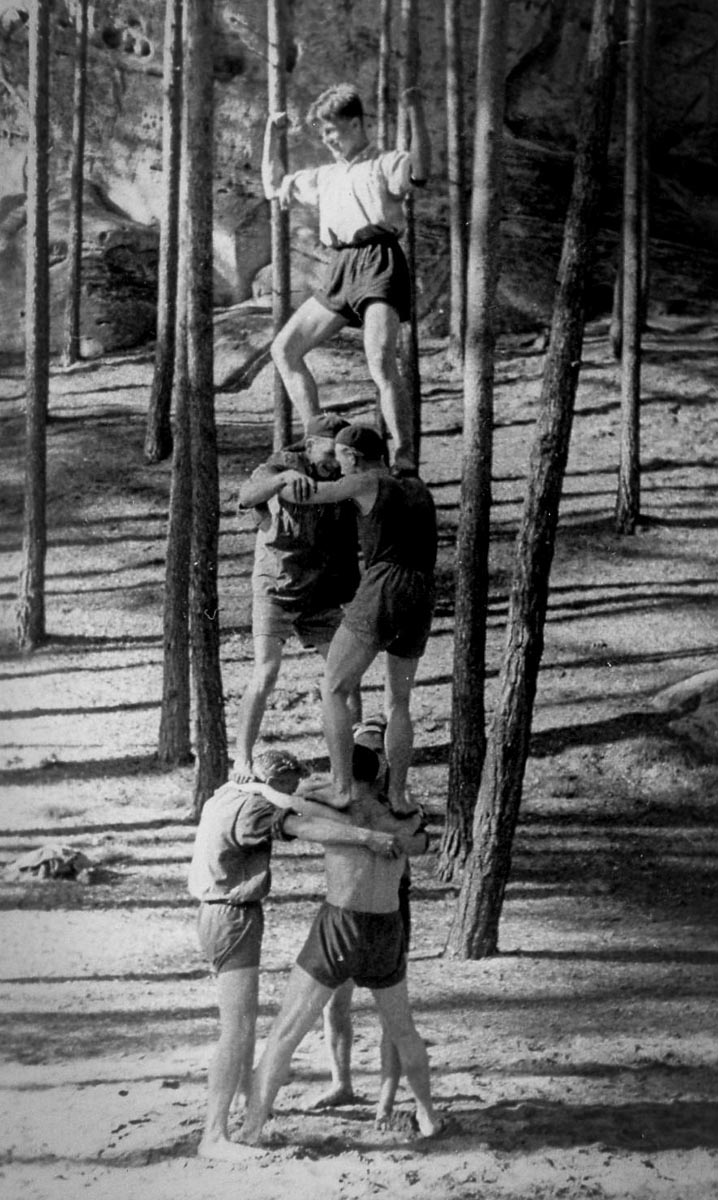

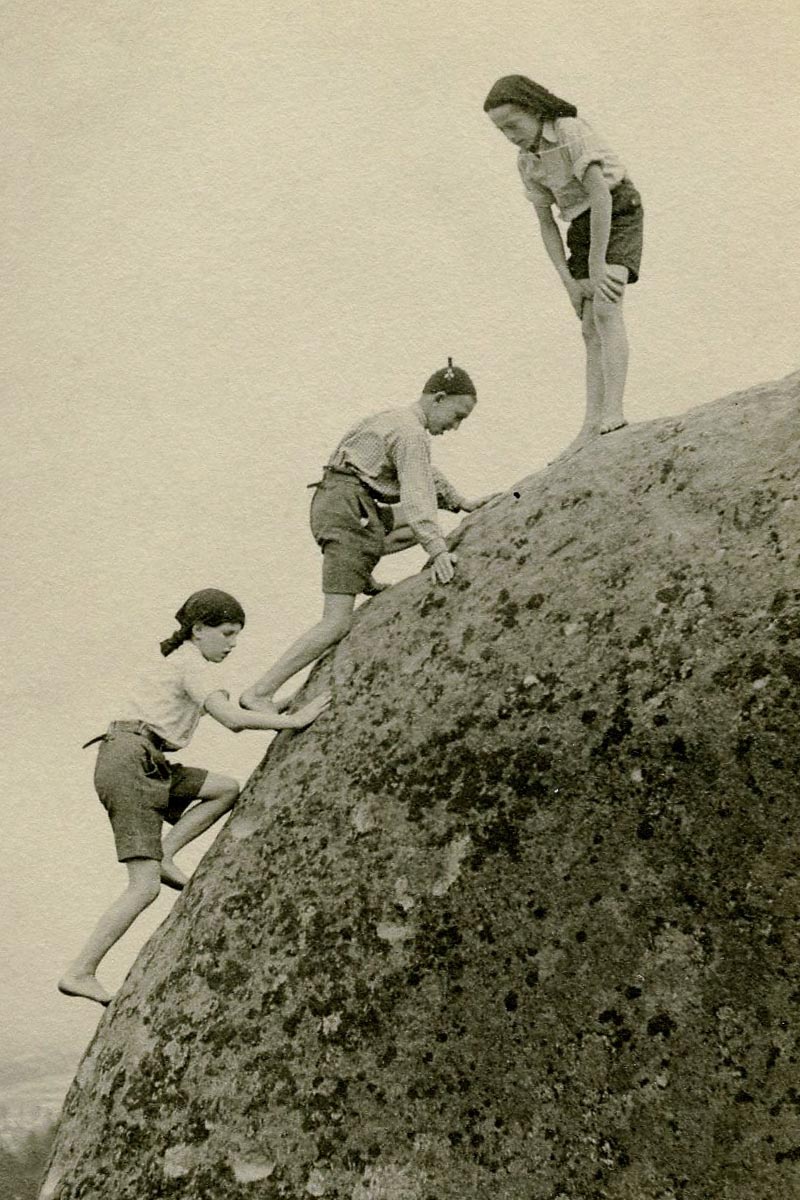

It sounds a bit like a physical equation: where there was resistance, there was Bogan. He led the way for his generation. He made his position clear already when he was fifteen years old, when he set out with his friend to climb the iconic Kapelník tower with an eight-meter piece of rope. On their way down, Bogan had to hold the rope while his classmates climbed down on it and then he carefully downclimbed the rock.

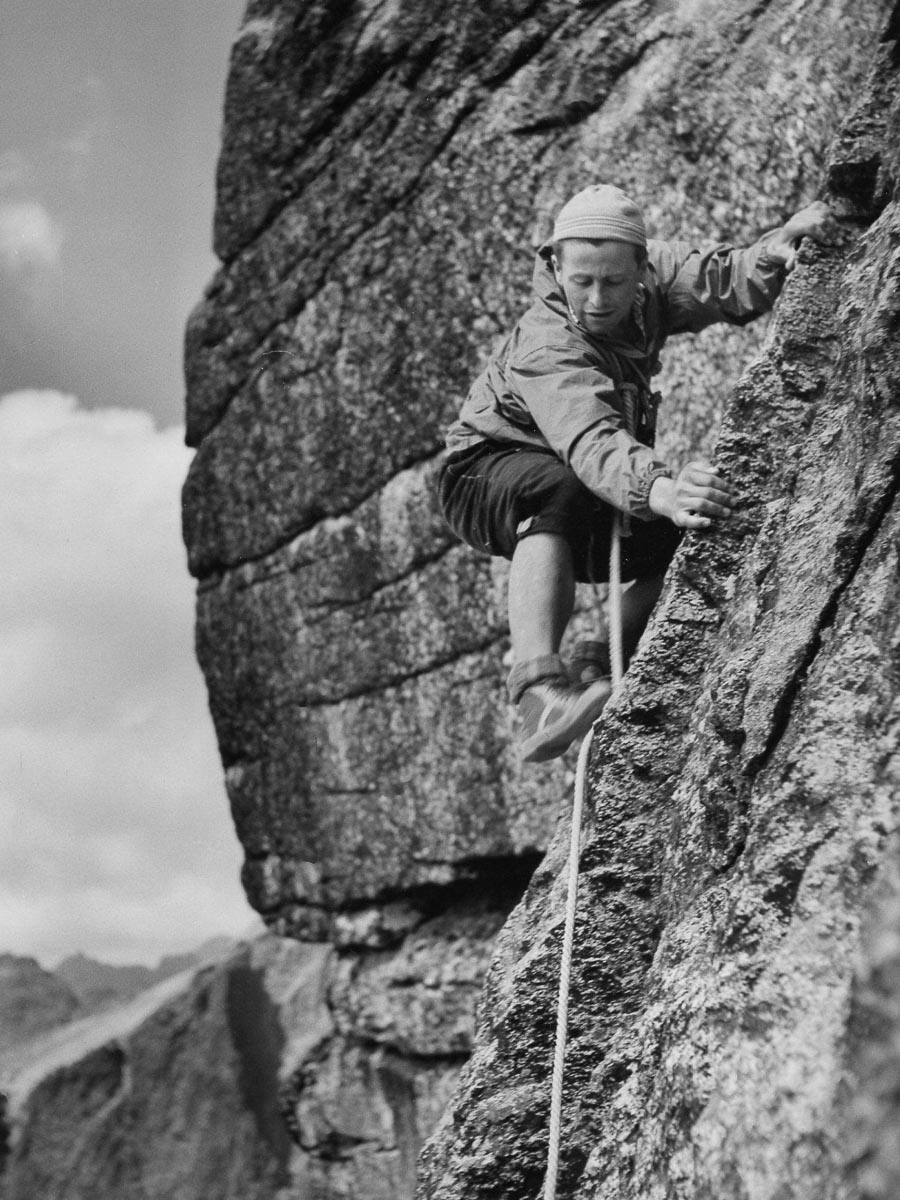

Bogan Svatoš (born in 1929) was one of the first climbers to repeat the “Smítkova Cesta” at Dominstein – the first Czechoslovakian VIIc (6a+ fr.) made in 1944. Later, he tied to the sharp end in the High Tatras at the “Hokejka” when Vilém Heckel was taking pictures of it for his book. When he and his mates started building their cottages in the Skalák area together, guess whose cottage was the first…

Soon, he and his friends started dreaming about the Himalayas. They envisioned the first Czechoslovak expedition to the highest mountain range of our planet. They were lured by paths not yet trodden by many white feet. Bogan, however, did not keep that plan just in the realm of dreams and started realizing the expedition. He was not afraid and came to Škoda automobile manufacturer to ask: “Could you lend us two minibuses for our expedition?” Surprisingly, they agreed. So the mainland transport was secured. “The rest we can handle.”

At the beginning of June, two years have passed since Bogan’s death (June 7, 2019). On that occasion, we decided to publish a previously unpublished interview which took place in his apartment in town Liberec in 2018.

The author of the article did not originally come to Bogan to make an interview, but as usual – it is so easy to get lost in time while talking to the experienced elderly climbers… and suddenly you find yourself chatting for the whole afternoon. This interview should remind us of the great man whom we miss so much. If all the people in the world were like Bogan, the life would be pure fun and there would be no problems…

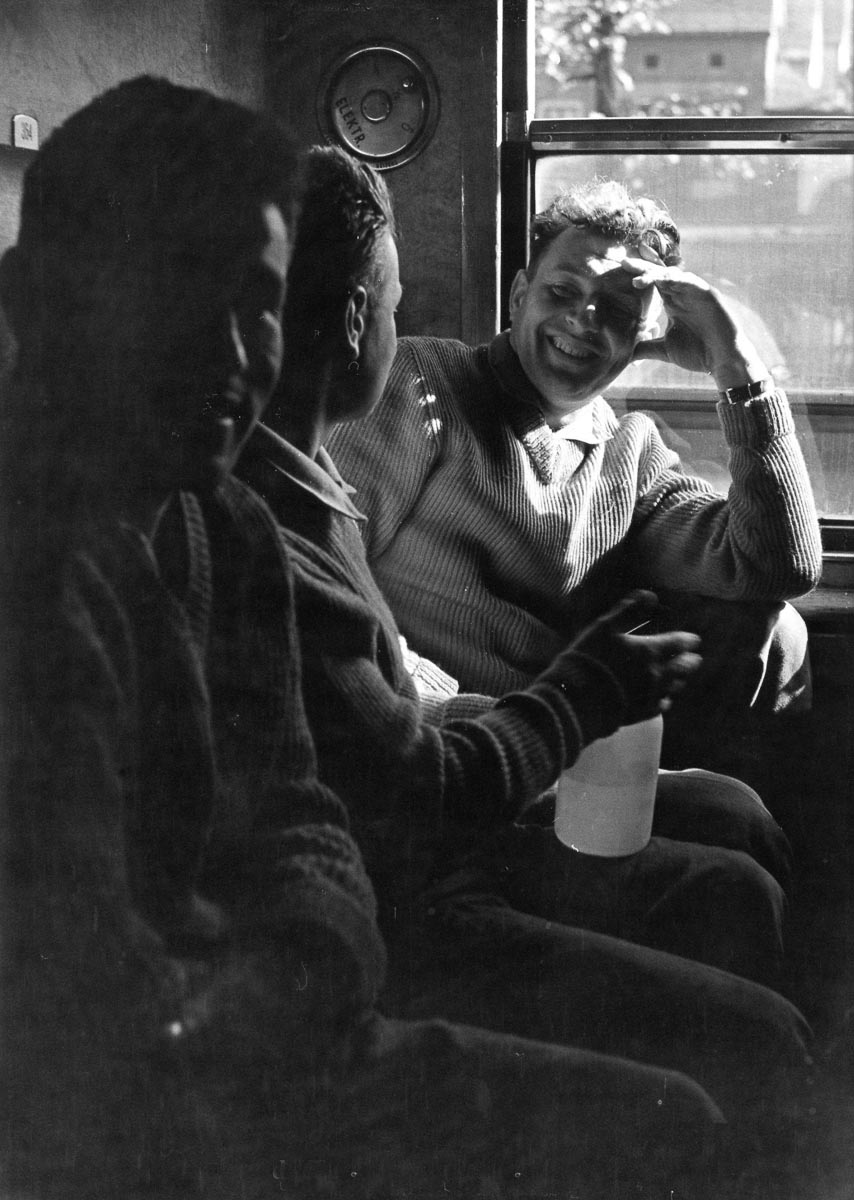

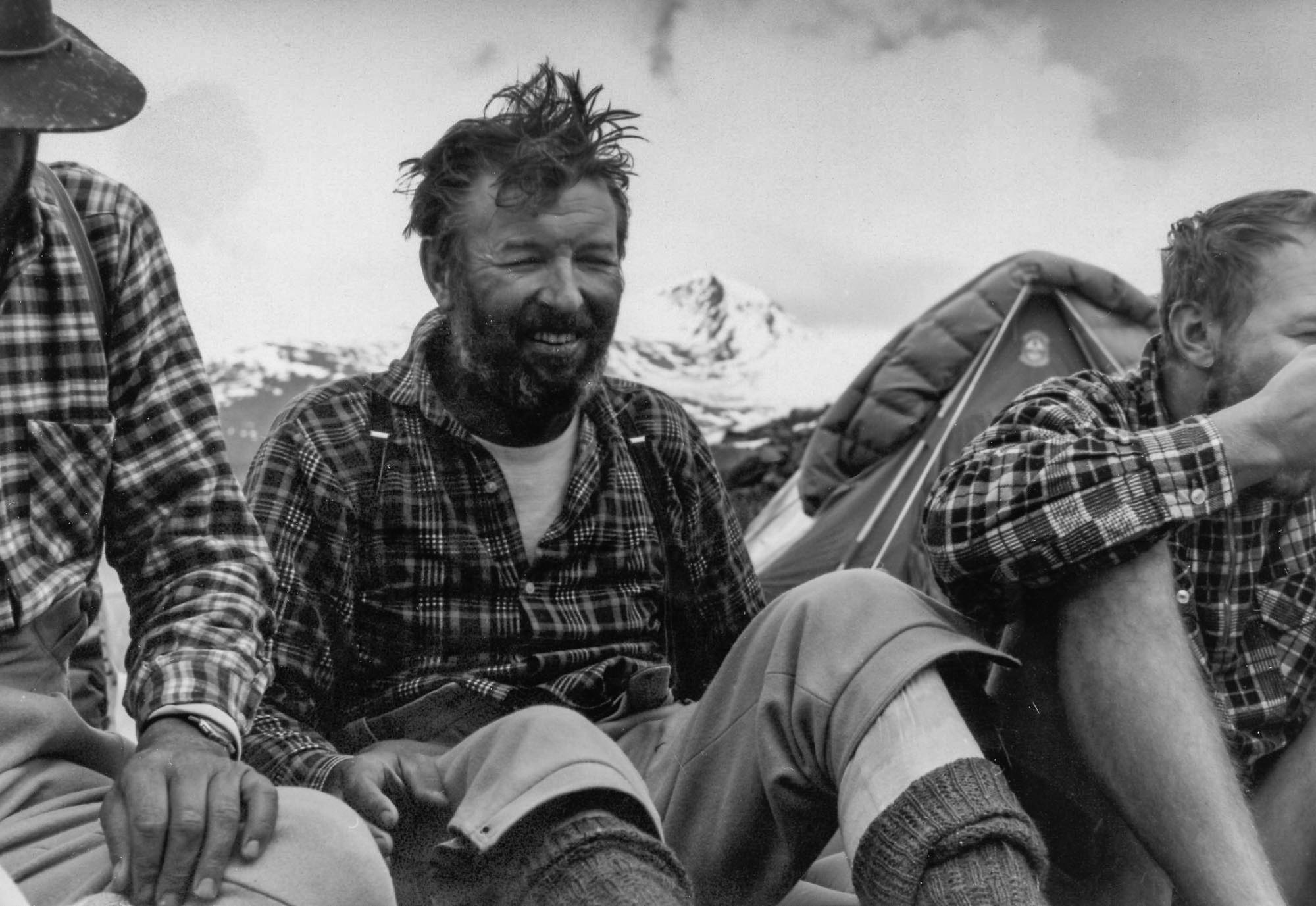

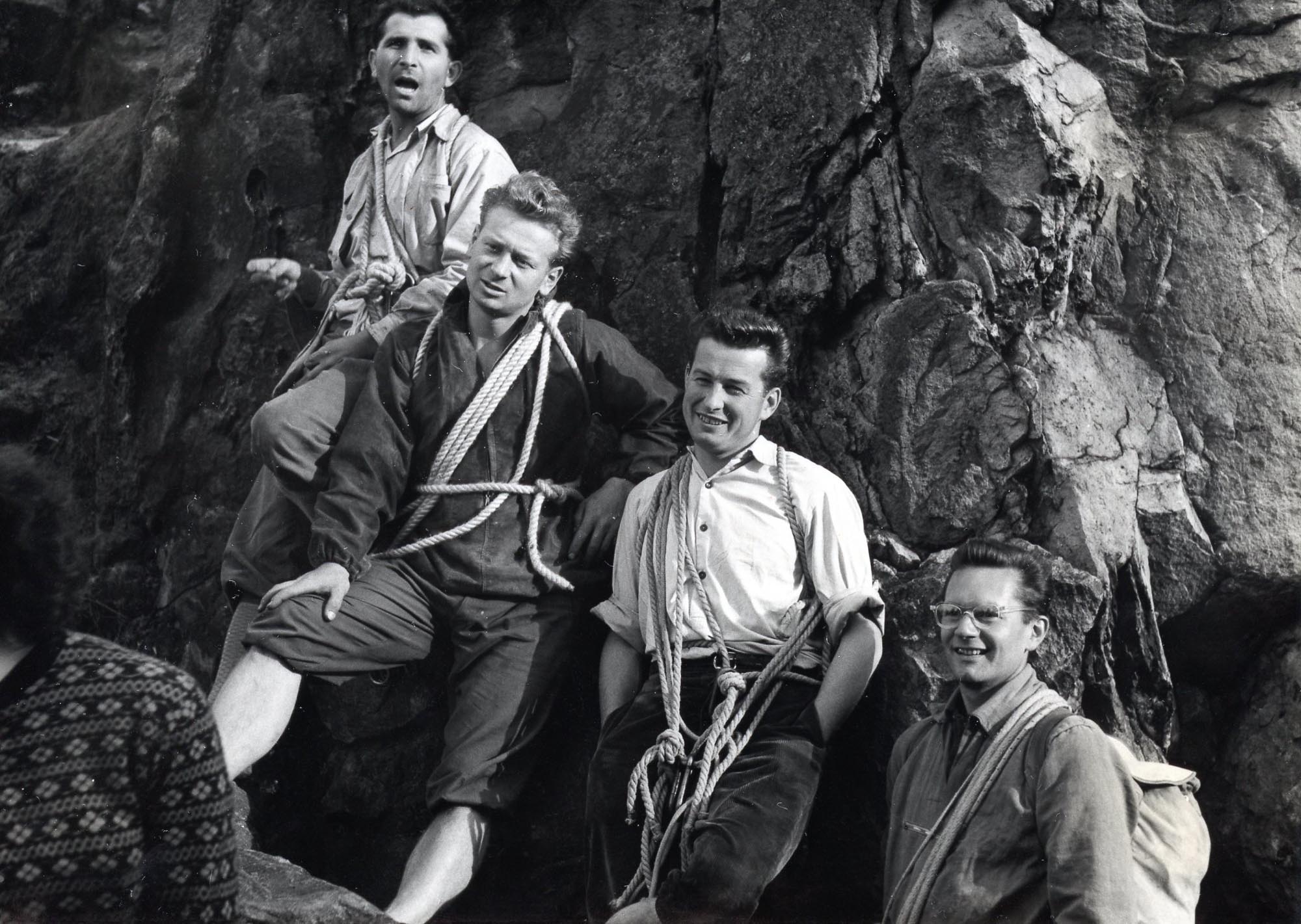

He had this photo from the Lomnický štít on his wall. “That was quite a pickle, I tell you,” recalls Bohouš (the more formal version of his name “Bogan”) a storm that caught him and his boys in the upper part of the “Hokejka” route. In the picture, the men are already laughing – they took it on the following day when they already forgot about the sudden snowstorm that caught them right on the wall.

LOADED WITH FUN

Do you have any pleasant, relaxing memories of the High Tatras?

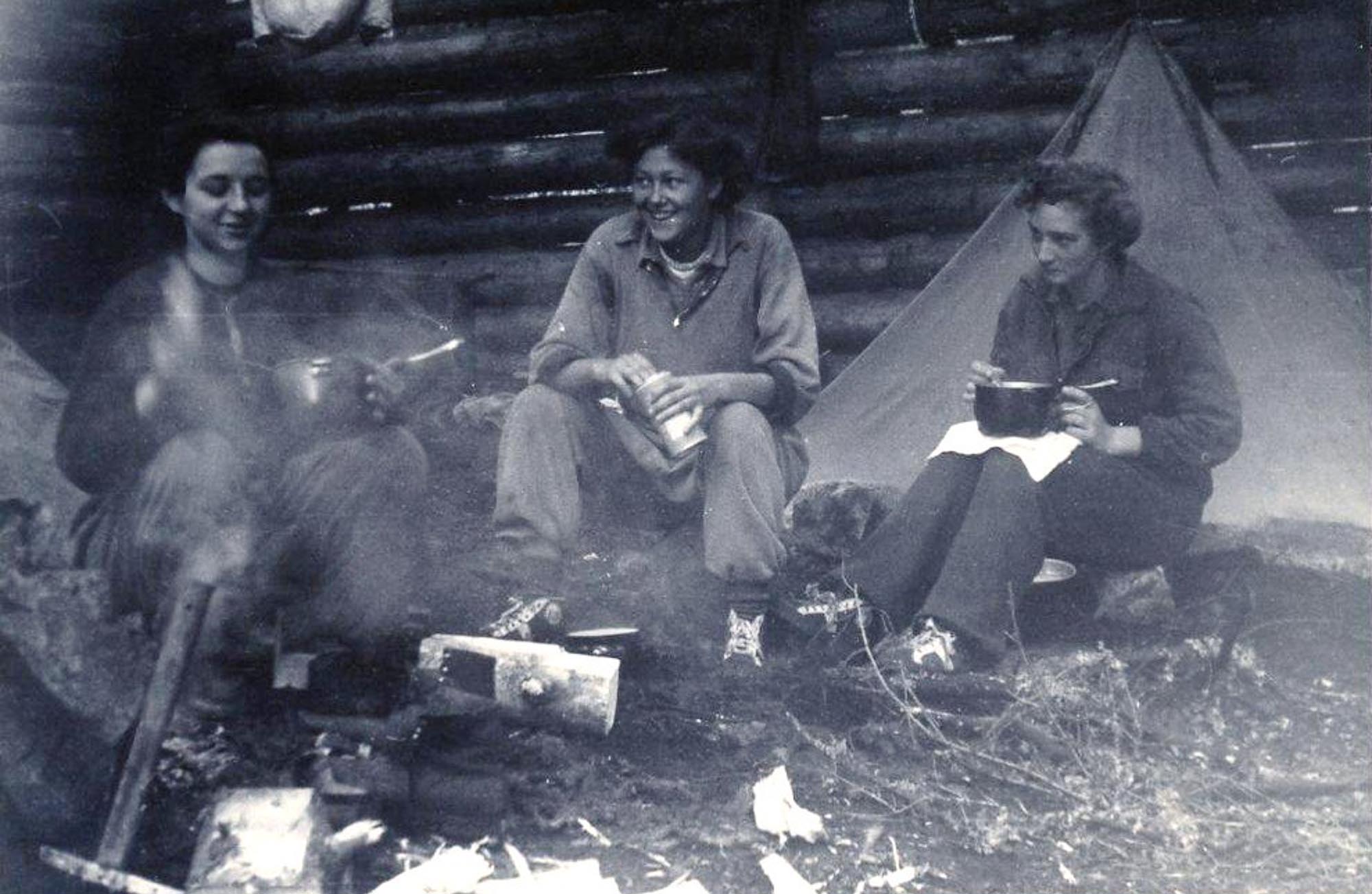

The summer 1953 was a nice leisure time for me – I was working as a load bearer at the Téry cottage which was supervised by Jarda Sláma back then. We stayed on it together with Karoušek and Bogan Nejedlý, my cousin. When the weather was nice, we just went climbing.

I already had a regular job back then, but I managed to cheat it a bit. We found a doctor in Slovakia who sent a message to my employer: “Mr. Svatoš currently cannot go back to work because he’s lying on Téry cottage with a sprained knee.” (He laughs) So I stayed there for two months being “incapacitated.”

How big loads were you carrying back then?

Sixty kilos were the usual load. When the weather was bad, we went twice a day. That’s why my legs are so ruined today. (He laughs.)

What are your favorite ascents in the High Tatras?

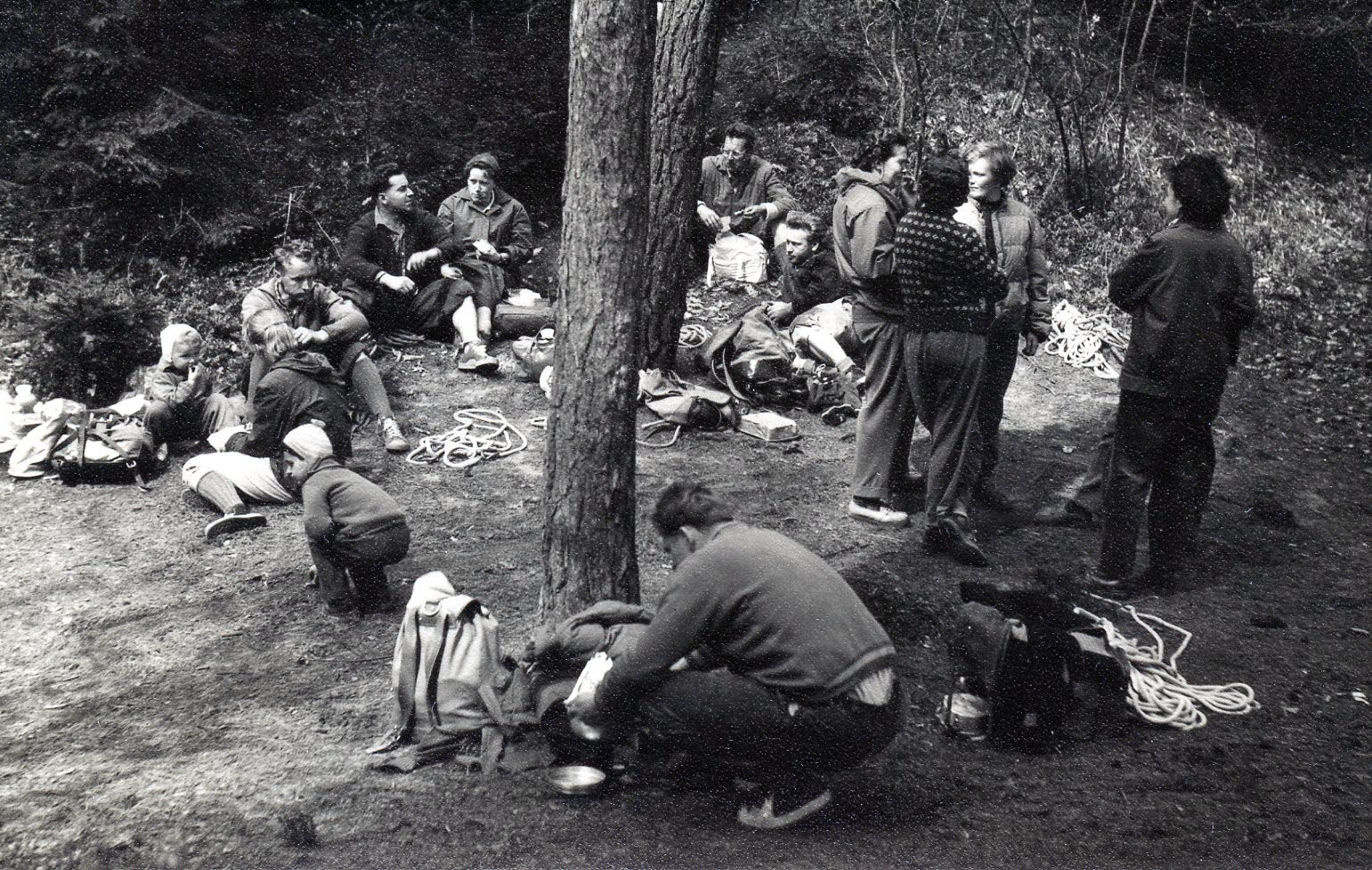

For example, the aforementioned “Hokejka” which we climbed in 1954. And then I remember mainly the splendid crossings. With three of my mates, we did a winter traverse of the High Tatras – namely Radan Kuchař, Karel Cerman and Jiří Mašek. A year later, the same crossing was done by the entire Czechoslovak national team in an expedition style.

I also did a summer crossing of the Tatras with Radan. We did it in three and half days and avoided just three parts – the “Mnich”, then the grade five section of “Východní Štít” which is just above the section called the “Železná Brána”, and then a small tower at the “Černý Štít”. We had a lousy rope and we were afraid of abseiling on it. You could only climb on that, not abseil. (He laughs.) You see, we trusted each other back then.

How do you remember the later winter crossing of the High Tatras done by the whole national alpinist team?

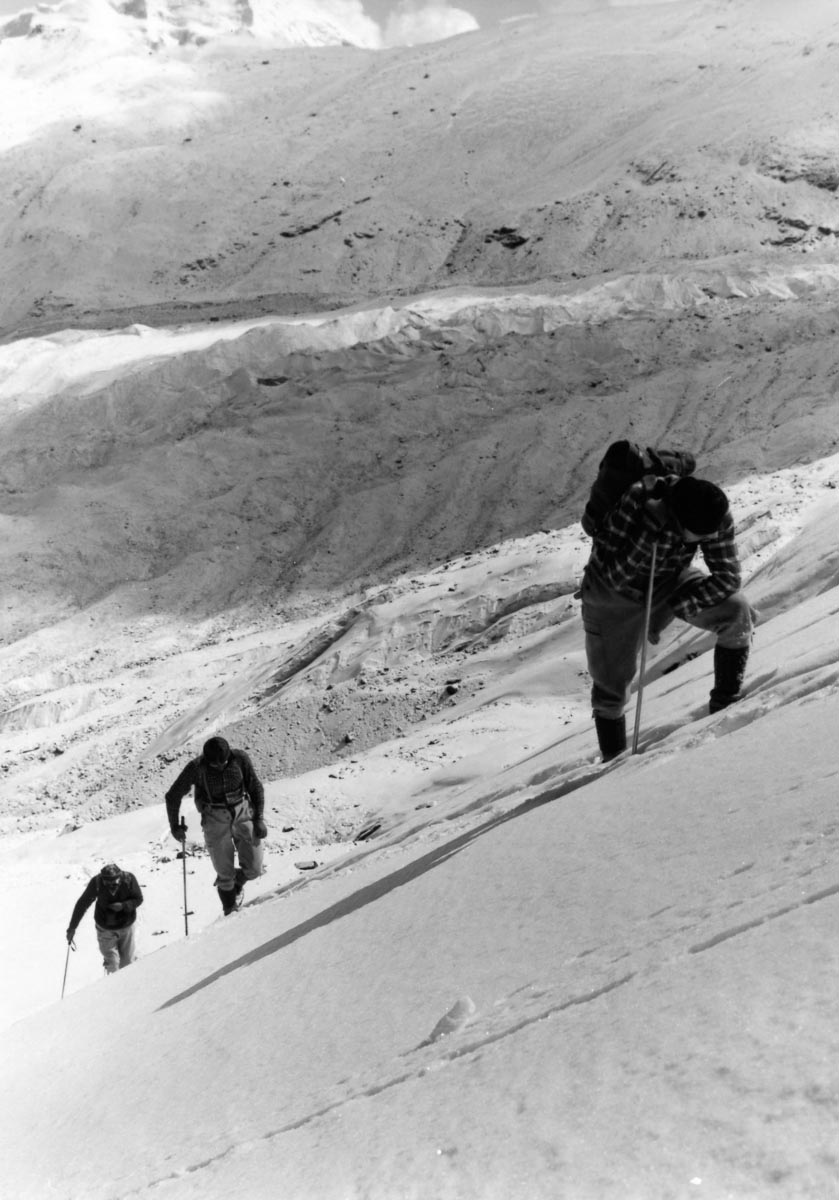

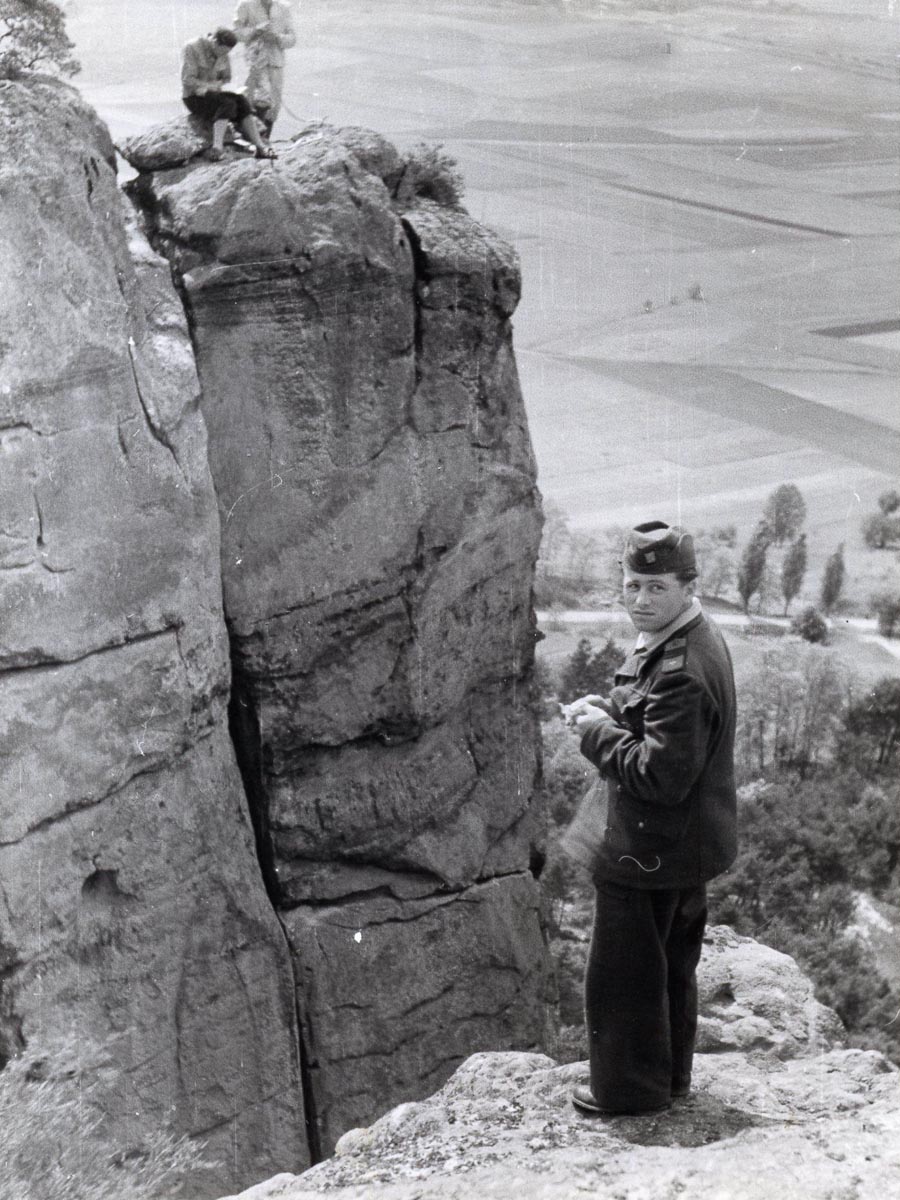

At that time we were training and preparing for the expedition. We always pitched a camp somewhere and then others took it down, brought it somewhere else and a selected team meanwhile climbed the surrounding ridges. We took turns. My team consisted of six guys from Liberec and the supervisor always chose the hardest lines for us.

In the pictures, I noticed you were using the Tricouni (special bolts and screws used instead of crampons). Young mountaineers probably don’t know much about them today.

I made the Tricouni myself. I started with a plain metal plate so I had to drill and bend everything by myself. It took an unbelievable amount of time to make them. You had to make two pieces of Tricouni for each shoe – the front one and the back one. After drilling the pieces, I had to further cut and polish them. Only then you could bend it and harden.

CHAMONIX 1955

In 1955, you took part in the first national team’s trip to the Alps. What did you climb there?

It felt more like an exploratory trip. With Radan Kuchař, we climbed four or five peaks. Of course we went to the highest peak as well – Mt Blanc. I remember climbing Dent du Géant, the Giant’s Tooth as well.

Was there the thick fixed rope on Dent du Géant back then?

Of course not. At that time, there was still rock climbing in the classic route.

What happened after that?

Then we tried to climb through the hard wall over Montenvers… At the Dru! But the weather betrayed us there. It started to snow and hail, so we had to retreat.

Did Radan and you already have a rope on which it was possible to abseil?

Fortunately, yes. But we weren’t that high up, we turned around when we were about a quarter of the route up.

Did you return to the Alps later?

I started having more problems with my leg. Then I had to go for a surgery. “Just leave it for a while. Allow yourself a year or two of resting,” the doctor told me. So I had to give up climbing for a while.

“We had a lousy rope, there was no way you would abseil on it.”

THE WAY FROM SCHOOL

Anyway, you recovered from that over time and got back in shape before you went to Annapurna.

That was in 1968, when we suspected that we needed to seize the opportunity before it was too late. “We need to do that while we’re allowed to,” we thought. And in 1969, we made it.

But then they sacked me out of my job and I was not even allowed to finish my studies – I was attending evening courses to complete my degree in the industries and during my first two years, I graduated with honours… They blamed me a lot for being so carefree to set out on such an expedition. “The factory doesn’t need you anymore,” they said. So I became a full-time driver.

What did they blame you for? Do you think that they treated you like that mainly because of envy?

I left the communist party even before the expedition. After Dubček was forced to leave his office in April 1969, I wrote a letter: “I am withdrawing from the party to protest against the occupation of my country.” I resigned from the party and they never forgave me.

When we got back from the Himalayas, we secretly published the book Na Annapúrnu (“To Annapurna”) and the comrades found out. I gave out the book to my fellows from the factory. But of course the news spread… I learned that the local party then had a meeting where they argued: “How is it possible that he could still publish a book?” I did not publish it, though. (He laughs.) Fortunately, the communist era is over…

How did you travel to the Himalayas?

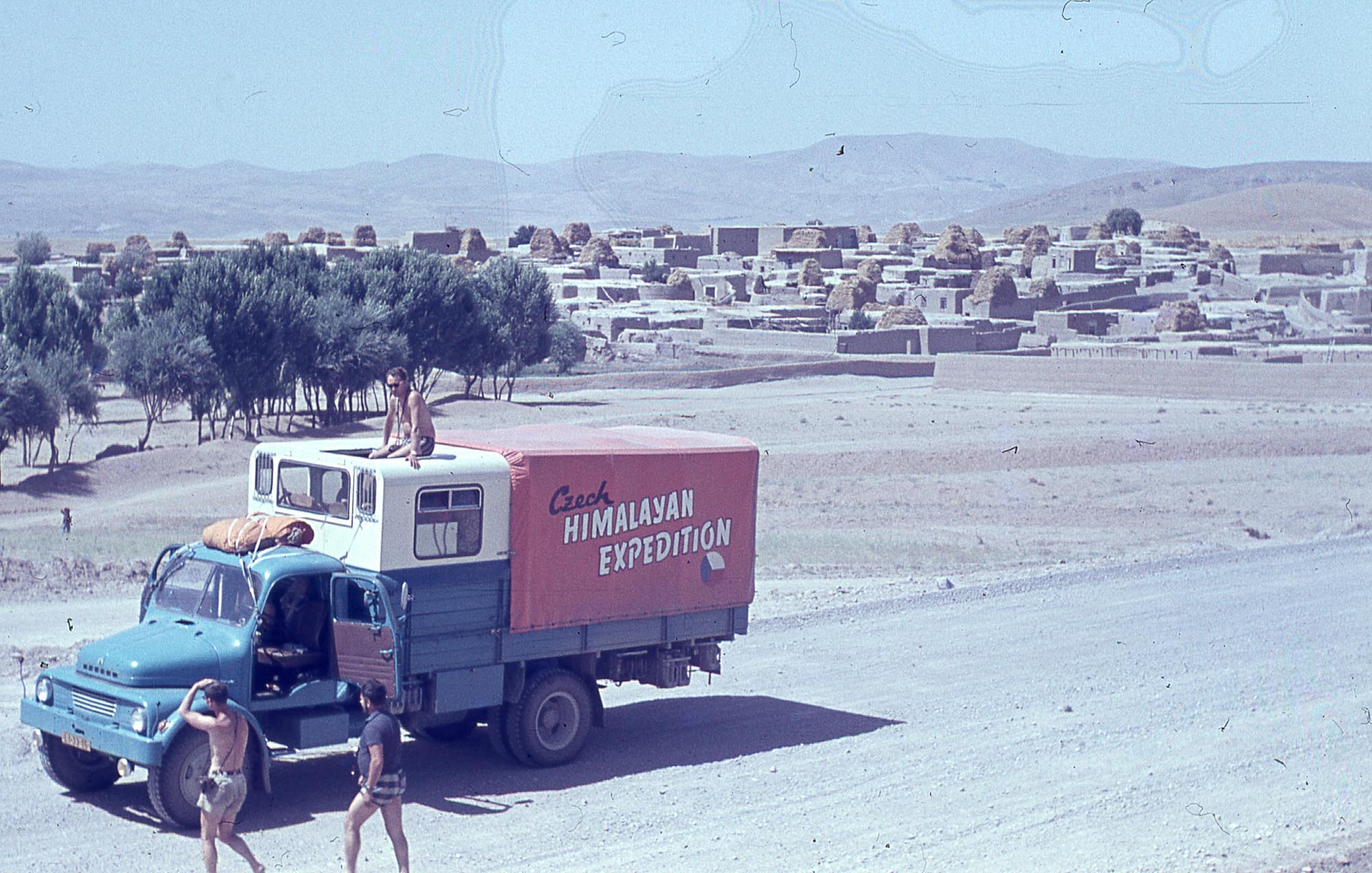

Škoda factory in Vrchlabí started manufacturing minibuses. So I wrote them if they could give us two for a test. (He laughs.) And they answered: “Come visit us and we’ll work it out.” So we went there with my friend Chroust, negotiated the conditions, and they really offered us two of their vehicles. It was just about time – 1968. But then we found that we could not fit the whole expedition into the two buses. We were supposed to leave in the spring of 1969 but then things got complicated and the factory could not wait until the autumn… So they refused after all, and we managed to get the classic Praga S5. And that’s the vehicle that got us all the way to the Himalayas.

So all those 800 kilos of food and 700 kilos of material fit in one vehicle?

Sure thing!

But you had to build in an extra cabin there, didn’t you?

Yes, they still allowed me to do that in my factory. They had still supported me back then. I drew the plans and apprentices finished it for me. I worked there as a supervisor, teaching them the craft – turning, measuring, and things like that. Those smart guys soon took over and created the Apollo module, as we called it. (Laughs)

So you came up with an elegant solution so that you could fit the whole expedition into a single vehicle…

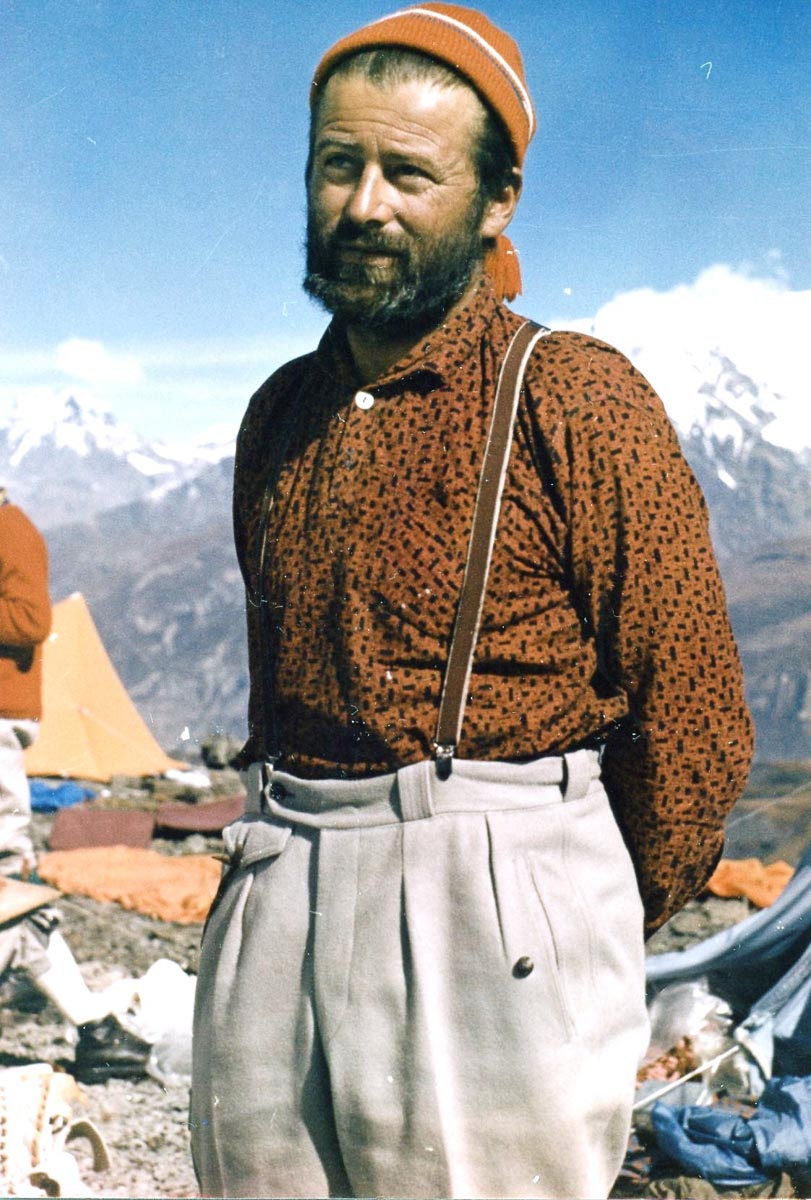

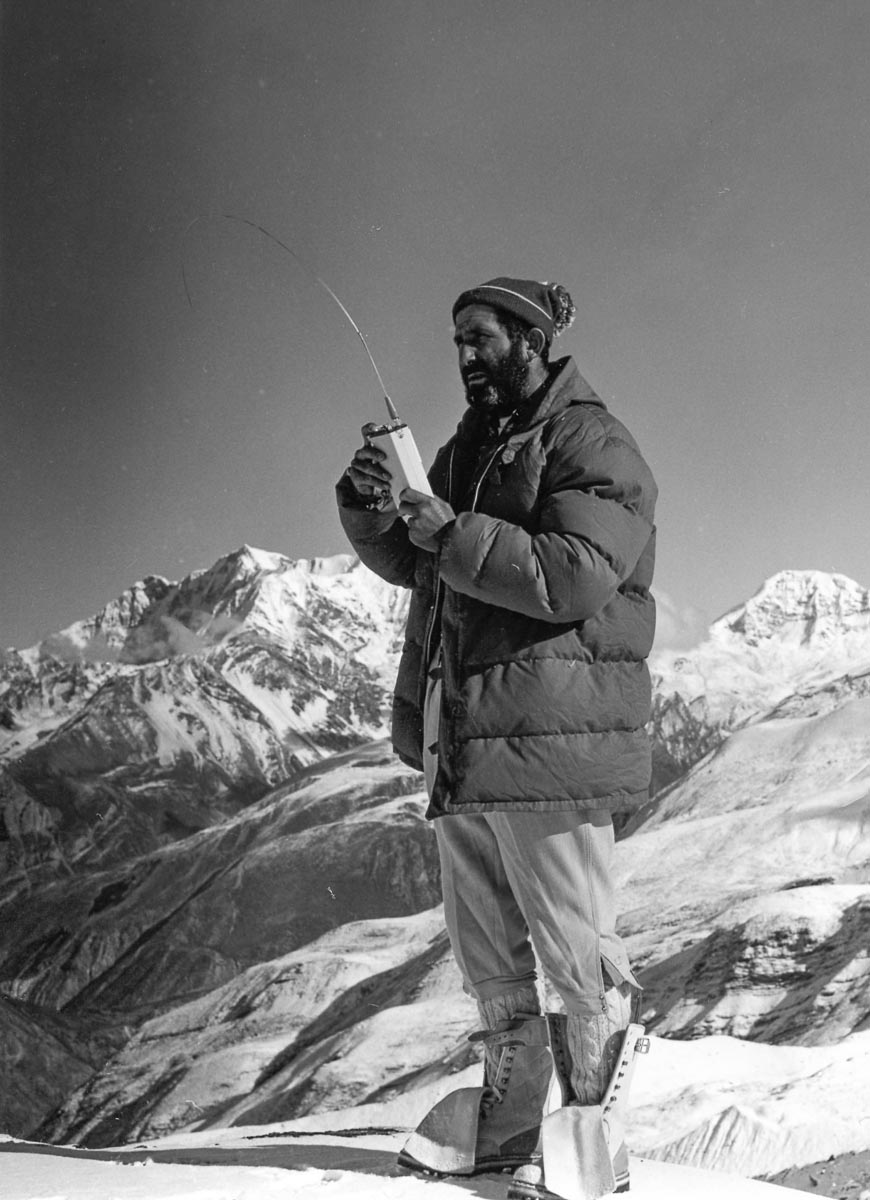

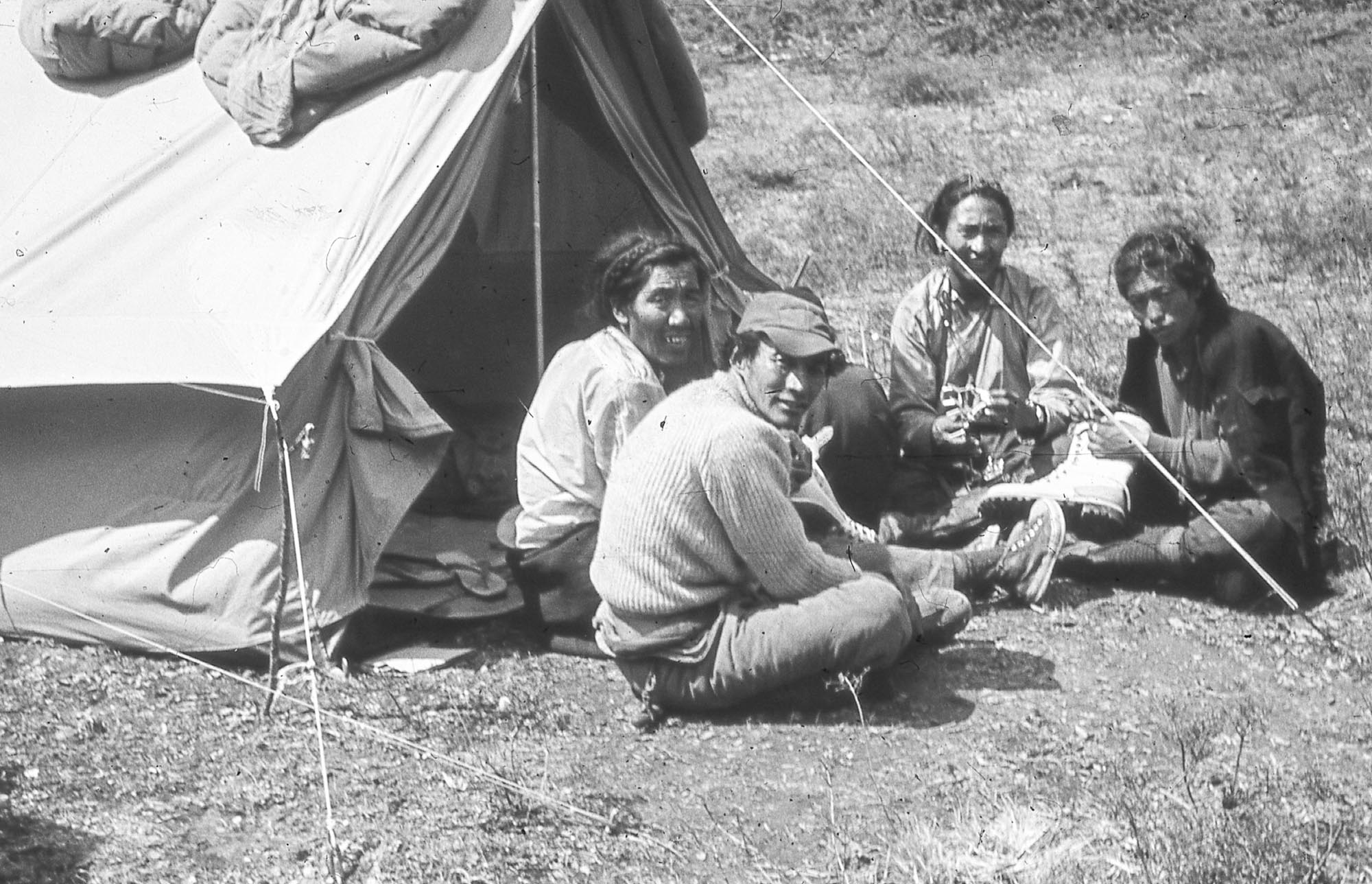

Nine people. We had agreed to invite the people from our usual climbing party. But then Chroust had a clever idea: “Let’s take two more younger chaps who are stronger than us.” The youngest even managed to get to the summit. (Miloš Albrecht and the local Sherpa Ang Babu got to the top of Annapurna IV, author’s note.) The other young guy didn’t make it and had to come back. I was seriously ill with an altitude sickness – I got meningitis and got completely blank for five days. I was just lying there…

At what altitude did it happen?

I felt sick already at five thousand, so I tried descending at least a bit… But then I collapsed and others had to drag me down. They got me to the basecamp where they called the doctor on the walkie-talkie. He managed to arrive on the very next day… It wasn’t easy but I made it through.

However, you were all successful in the end, weren’t you?

Yes, at that time, the success of the whole expedition was what counted. I often likened it to football – at the last minute one guy scores a winning goal and everyone celebrates. We won! (He laughs.) But nowadays climbers take a different approach.

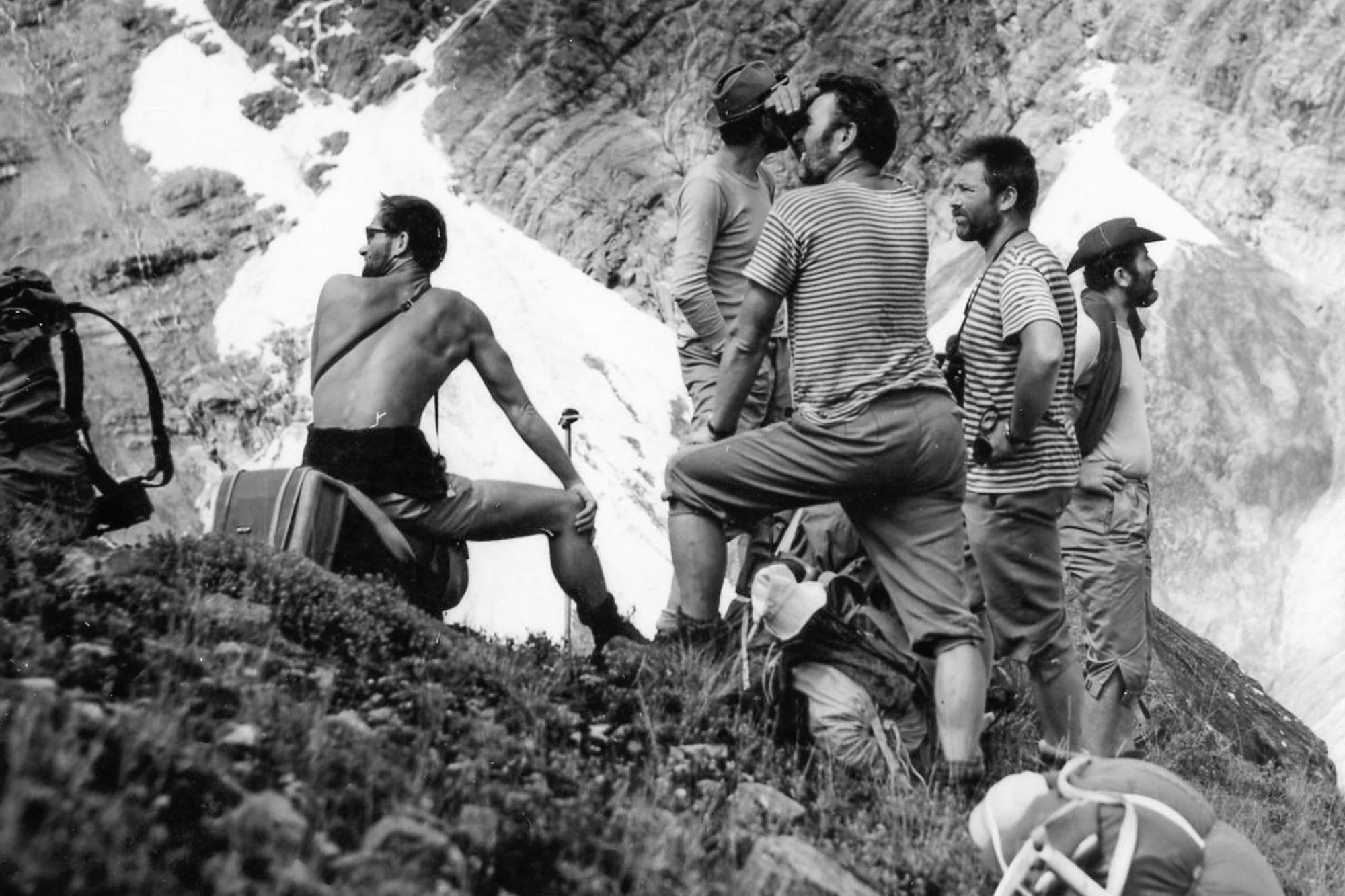

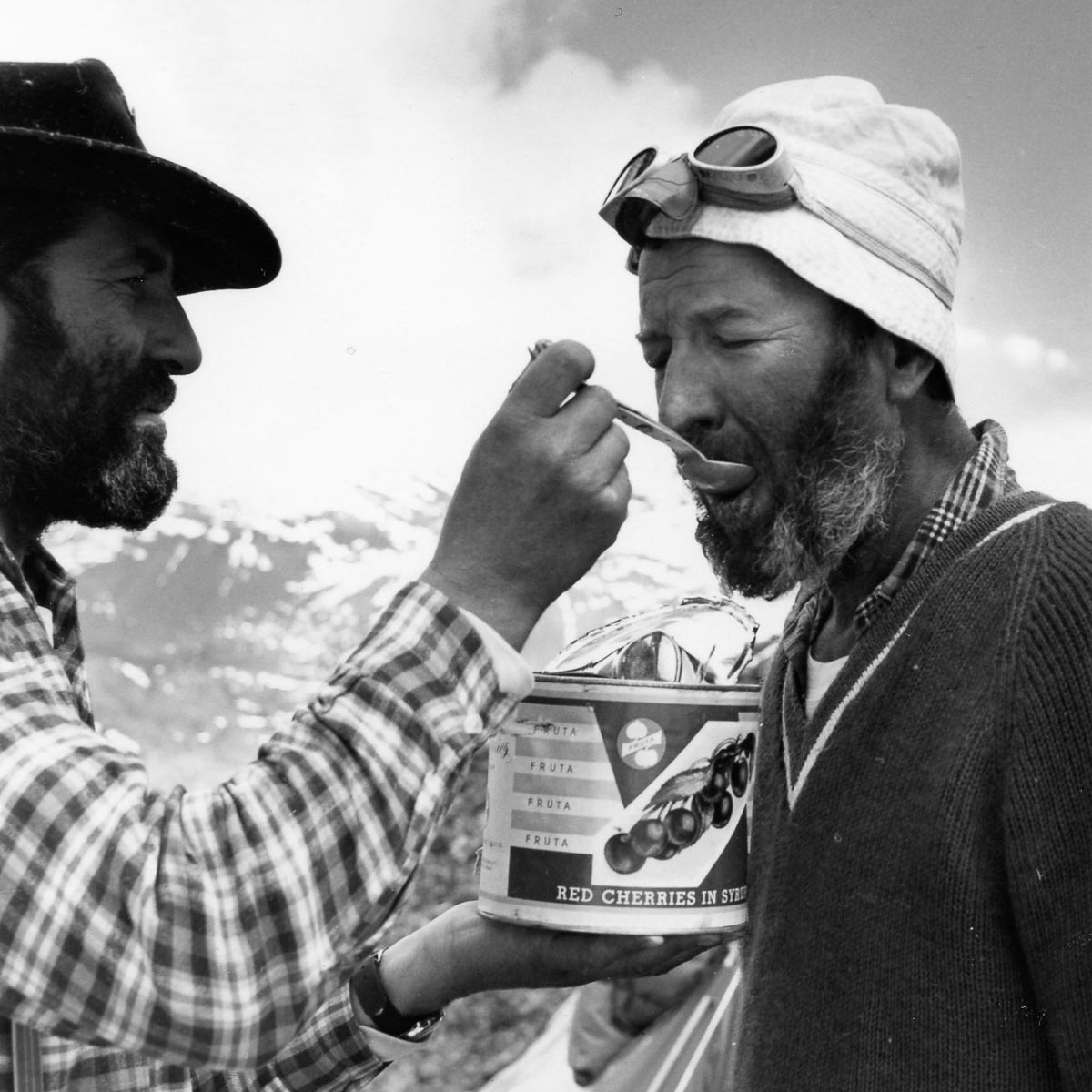

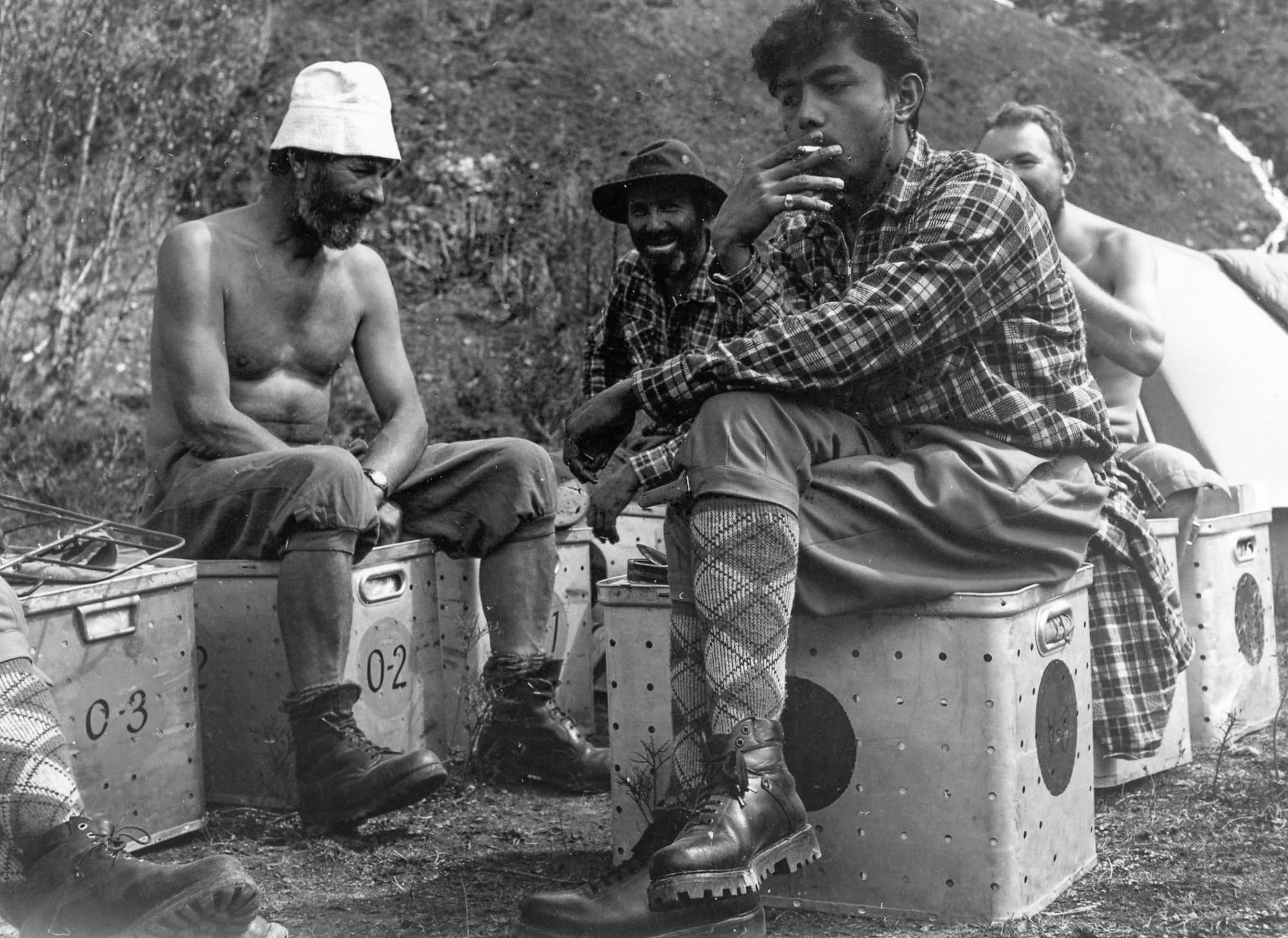

Lower row: Svatoš, Veselý, Ang-Babu Sherpa, Šimon

MINUTES OF SILENCE

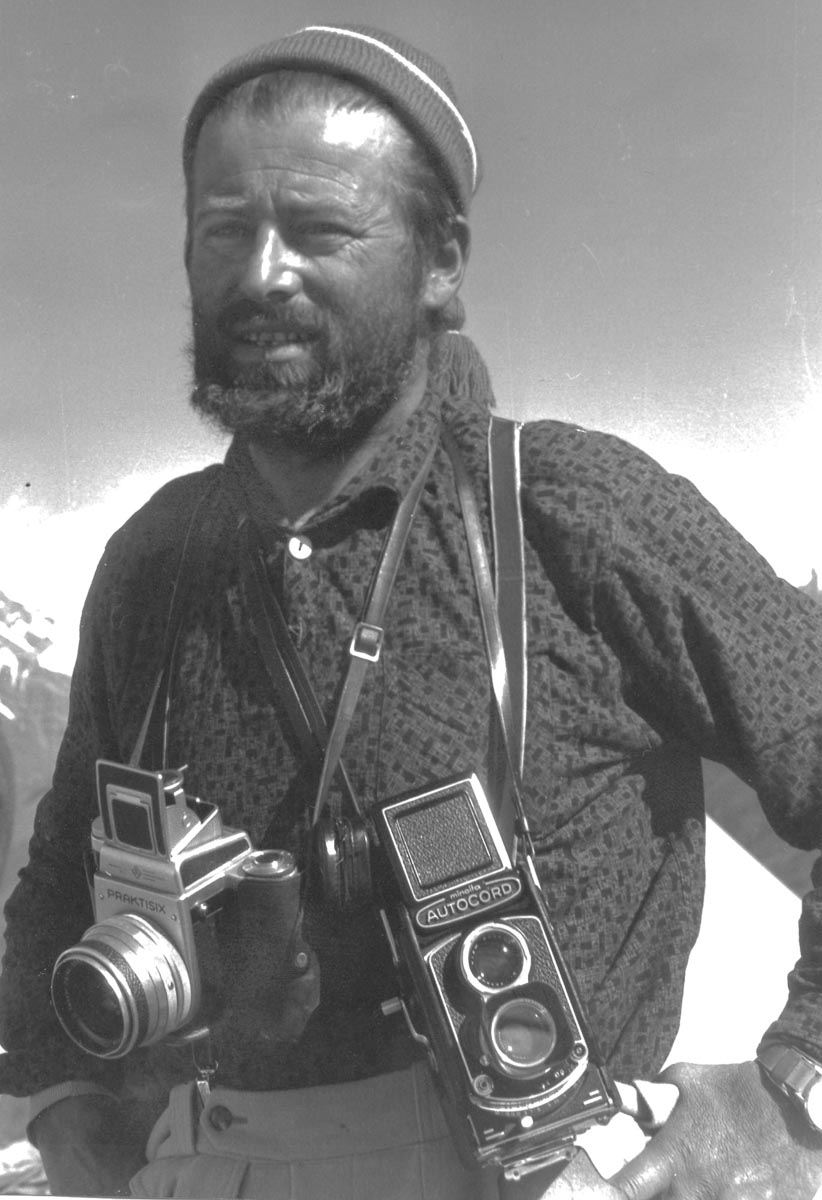

You saw a whole box of your camera films from the expedition falling into a river – how did it feel?

I wanted to jump into it!

So what happened?

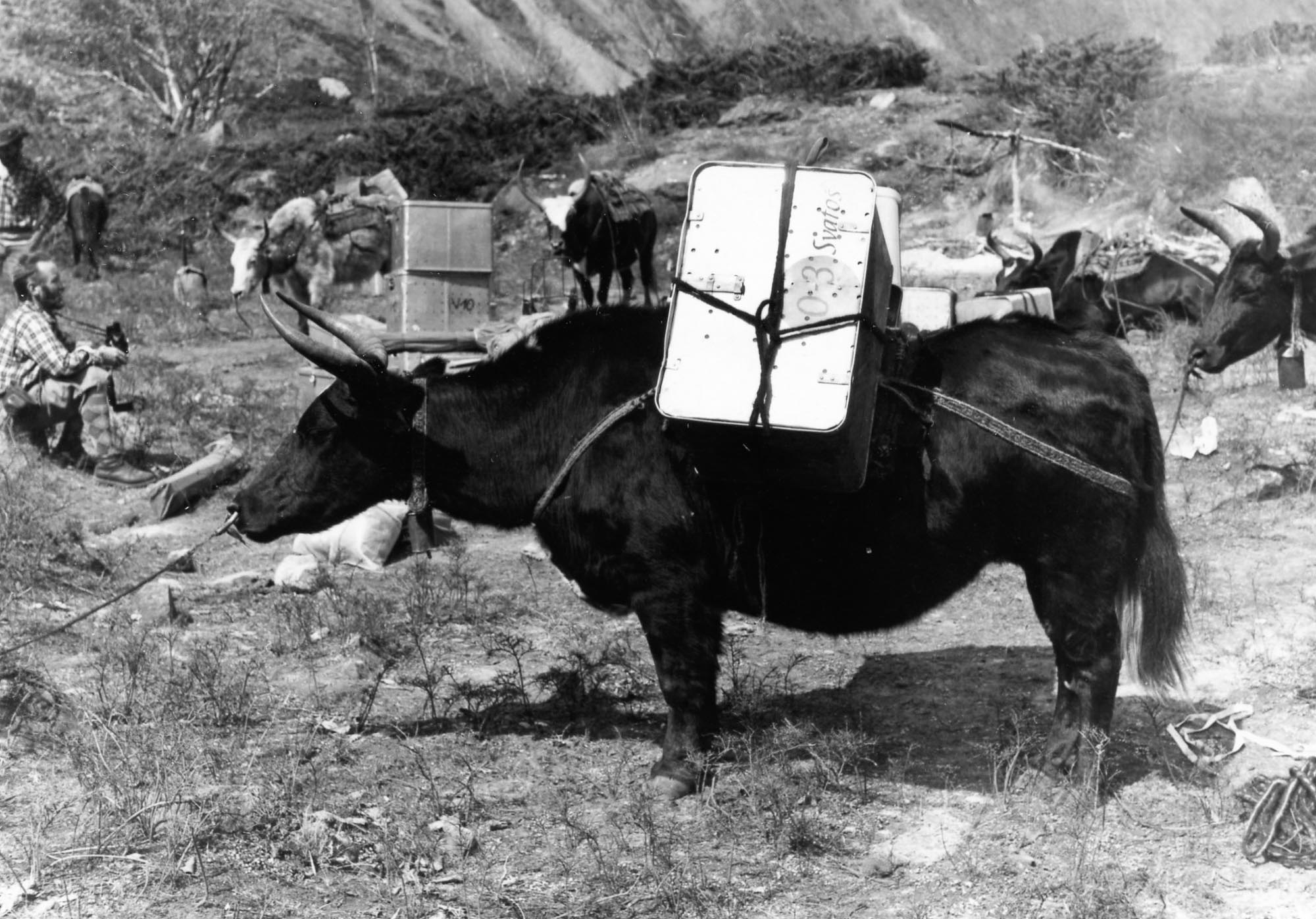

When we were tearing down the camp, we got around 12 dzos (a hybrid between the yak and cow) to carry the equipment. For some reason, me and Cerman’s boxes ended up on a particularly vicious dzo. As we walked down the slope above the Marshandi River, the bastard managed to shake down those two boxes from its back straight into the current. They flew down the slope… Karel Cerman’s box fell apart along the way, but my box held together until it fell straight to the river. So everything went down the stream. My stuff included the big box with all the undeveloped films – all the visual material I took along the way. About 80 film rolls. All of that was in the box.

All the material from the expedition?

Yes. All the films were there. But other equipment as well – there was my sweater, trousers, shoes – all of that started swimming away. But we suddenly noticed that the box with films stayed intact and hung on a rock on the other side of the stream. We knew there was a footbridge on the other side. The stone holding the box was about this big (he gestures a shape sized like a basketball). I was scared to death that it would not hold long enough. Vašek ran for it, caught it, and saved it for me. Fortunately, the box was secured with tape.

So it had a happy ending after all. I thought you lost most of the photos.

Only a few pictures that were outside of this filmbox swam away. These were photos from the last days, which we could not fit into the box – such as a picture of wild geese moving across the valley into the lowlands. Huge flocks flew just over my head. We lost these but were still lucky to salvage the rest. I was going crazy on the other side of the river. But then all was saved and we were so happy about it.

Is this expedition the greatest climbing experience you have?

Look, I think I can recall every single day of that trip. It was so memorable and I was living my life to its fullest. I just forget the names sometimes. I even have my detailed records, now on the computer, in addition to the diary that I often find myself coming back to. So I’m still updating it… It was one great experience. Every single thing on that trip just clicked and worked!

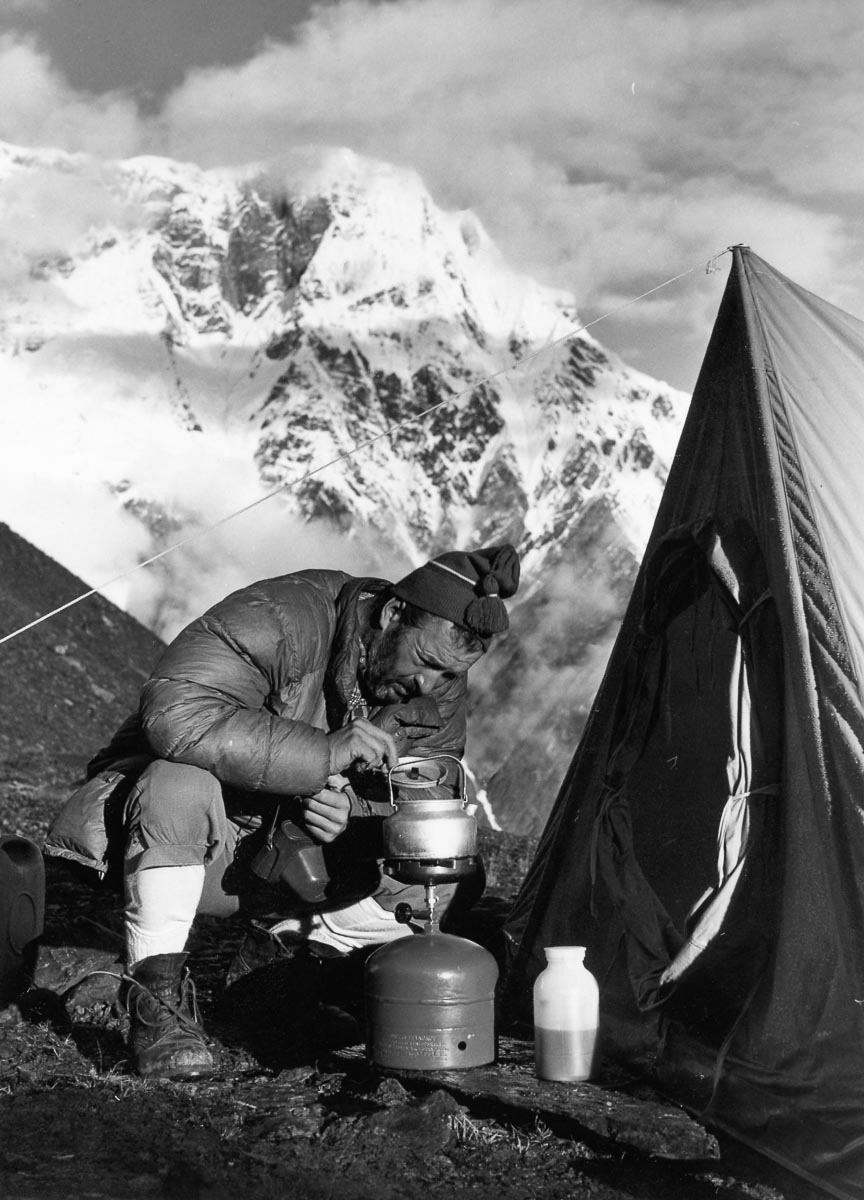

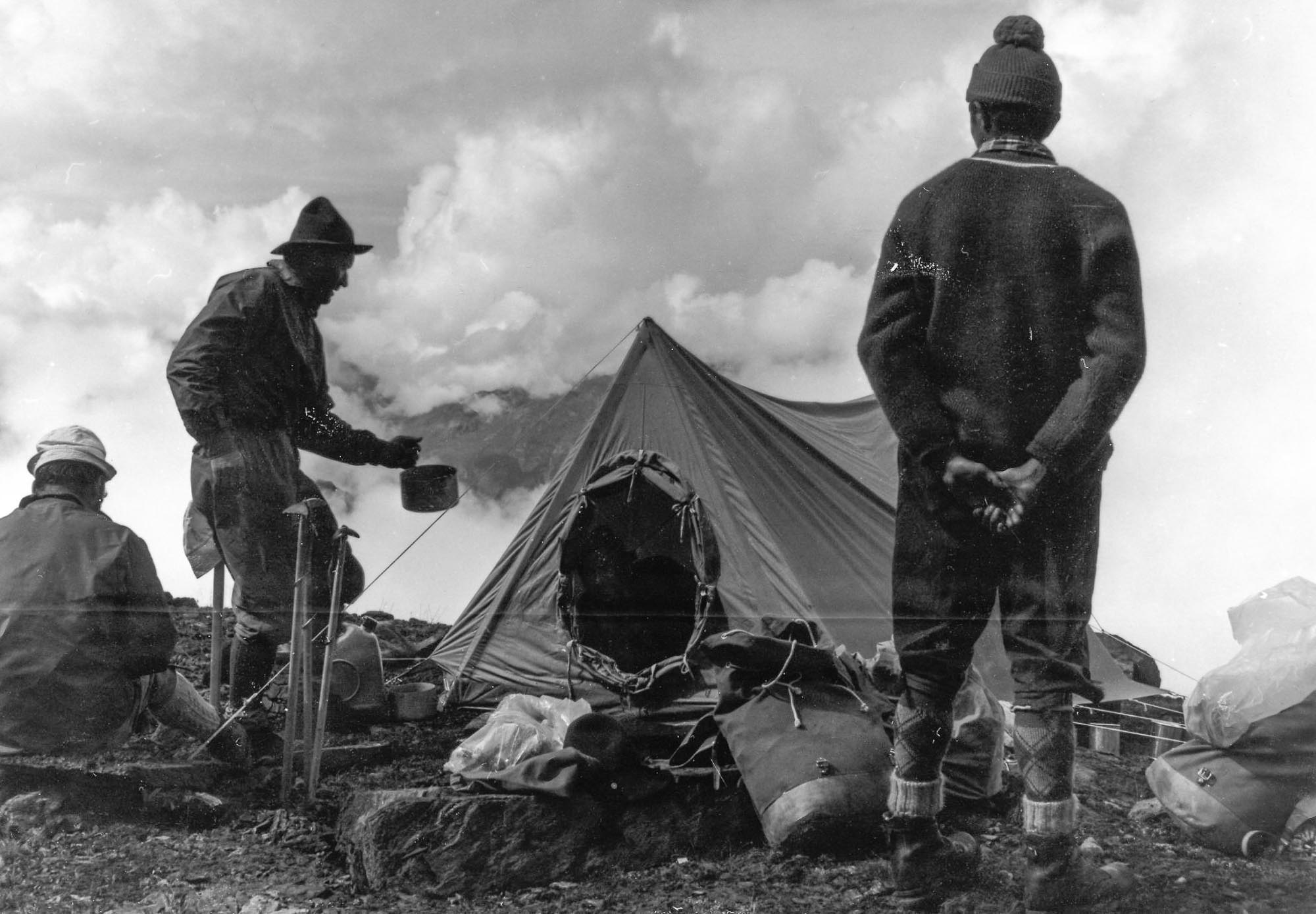

Even the packing. We had to pack 53 pieces of luggage. We had boxes, then we had bags… We had to count how much we were to eat in eleven people. In addition, there was a sherpa climber and an officer appointed by His Majesty protecting us. We had to provide food for those guys too. So we had to plan carefully and break down rations for every single day. Everything had to be divided into packs, each weighing 30 kilos. That alone took us a few days. Moreover, each border crossing meant negotiations about the allowed equipment and the price for passing.

There was no road to Pokhara from Kathmandu at that time, so you had to take a plane…

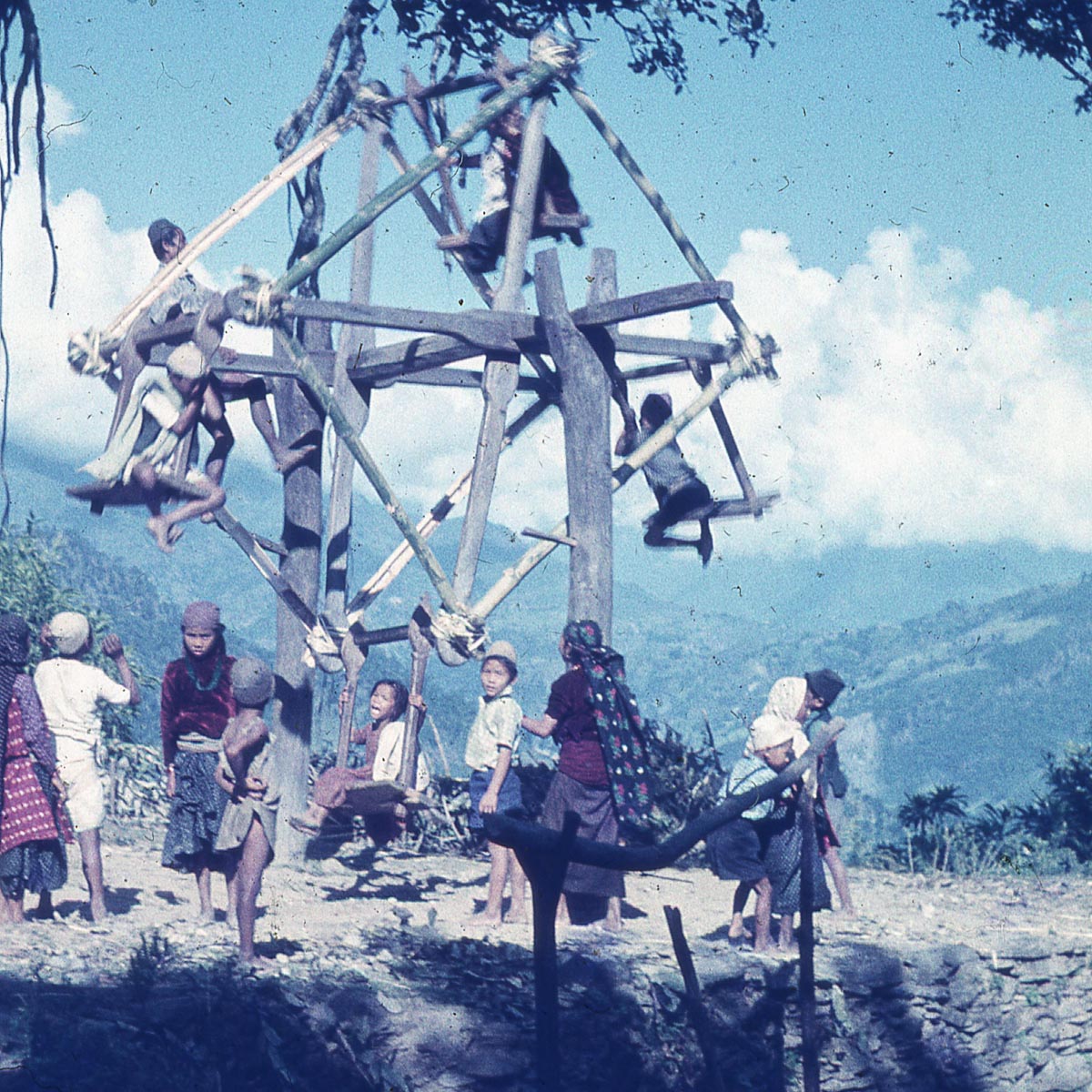

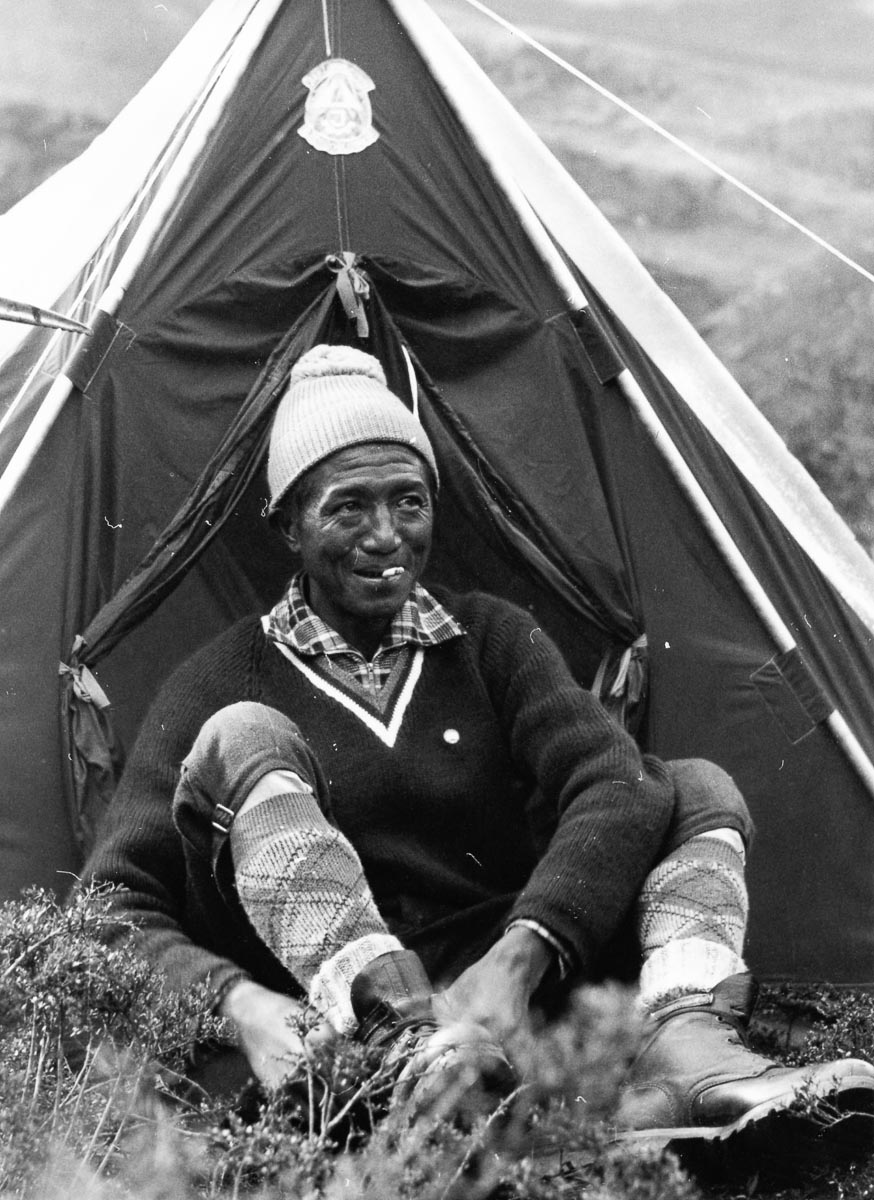

Sure, we reached Kathmandu by car and then we had to transfer all the boxes onto a plane. In Pokhara, 53 sherpas were waiting for us and each of them was trying to get the lightest one. Nobody told them they were weighing more or less the same. (He laughs.) Together with these guys, we managed to get all the equipment to the basecamp – 10 days of walking. Even that heavy hauling and hiking counts among the unforgettable experience, though. The mountains, changing landscape…

Did you get to Mustang?

We couldn’t because the king forbade us to do so. That was a shame, though. We thought we would return the other way around (via Jomsom, author’s note). Not possible. Our officer said: “I would get arrested for that.” So he had to take us back the same way. Nobody went through Mustang by then because the surrounding area was inhabited by the Khampa tribe which was said to be dangerous and violent. They originally lived in Tibet, but after the Chinese invasion, they fled from China via Mustang to Manang, where they settled. After all, we met them anyways. As we approached Manang, some guys on horseback caught up with us. The long-haired and muscular men started to argue with one of our bearers that we should not be passing through that place.

They made it clear that they would cut our necks if we didn’t get permission from their boss. So we waited all night to see what would happen… The soldier that accompanied us was all shaky. (He laughs.) After all, we’ve solved it with some of our sweets and cigarettes. Almost none of us smoked so we could keep giving out around 10 cigarettes to each bearer a day. We brought unbelievable amount of those. And we also gave cigarettes to the Khampas. Eventually, they started coming to our basic camp – they were sitting in front of our tents and rummaging through our cameras… Our doctor treated them there… Eventually, we became sort of friends with them.

Anyways, not so long ago, a friend showed me pictures of that places taken 50 years later. In my pictures, there is a pure landscape on a background of furrowed hills – a beautiful shot. In his pictures, you can recognize the same places but there are already telephone wires and some sort of “Annauprna house”. In the valley, through which we passed to the basecamp, there is a new powerplant. All the magic we have experienced while seeing that place for the first time is gone. We were the third European expedition that came there. Before us there were only the English and the Germans.

Have you ever been to the Himalayas since then?

Never. In 1980s, I went to Tien Shan. We climbed some five-thousand-meter mountains there. Even later, I mostly stayed hidden in my home Skalák area.

PLAYING HIDE AND SEEK WITH JOSKA

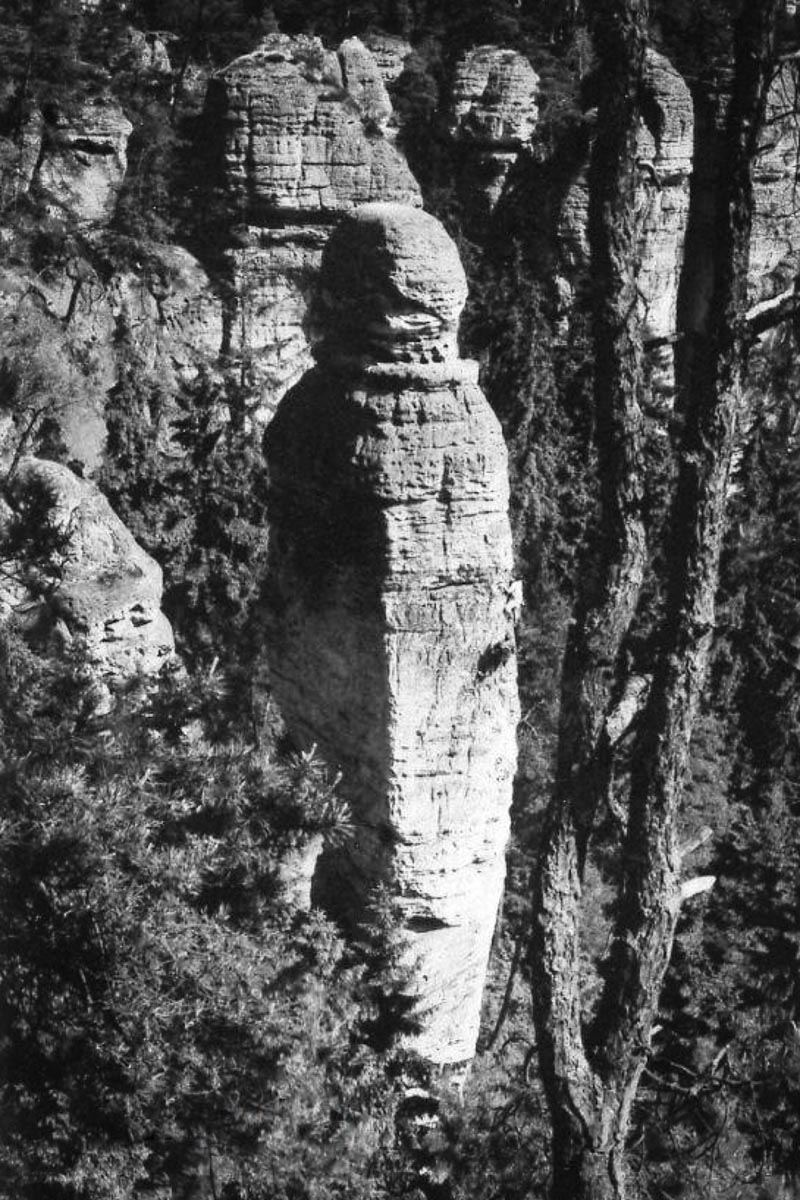

Are you happy that your routes in Skalák are still popular?

Of course. I even went for hernia surgery and my doctor told me: “I climbed one of your routes! At Dominstein.” And he began to praise the line… He was probably just showing off because the route seemed somewhat hard to me. But I was still happy to hear it. (“Svatošova Cesta” VIIb, 5c fr.)

Progress never stops. Everybody was stunned when Zátopek ran 10 kilometers under 30 minutes. And today, you have some hundred people all around the globe who can run it in 27 minutes. (He laughs.) Boundaries are shifting – in every sport. For us, it was different, we started all by ourselves and had to find our own way.

As you said you started by yourself… When did you actually climb the Kapelník tower for the first time?

It was in 1944, we were 15 years old. Three of us went there and nobody told us which line we should pick or how to do that at all. We told Joska Smítka about our attempt and he came to check on us if we’re keeping all the rules – if we really tie through the rings while we have them below our waist, if we’re not pulling ourselves up on the rings and so on… when we abseiled and climbed down, he came to us and told us: “Good job guys!” Then we sat around a fire together – I haven’t even realized how dangerous that was – he had already escaped the Gestapo twice back then.

There was a rumor that some Hitlerjugend boys stole your rope – is that true?

Yes, we had about eight or ten meters of rope. We even borrowed it from one boy whose father was a lumberjack. We didn’t really use it for abseiling because it was too short. It went like this: We left it hanging on a lower part of a tower and saw the Hitlerjungend boys stealing it, so we quickly climbed down and chased them to a pond where we surrounded them but did not dare to get into a fight because they had knives… After all, we managed to get it back from them.

after swimming in a pond. Bogan standing

on the top. 1940 – the boys were 11 years old.

When you turned fifty, you climbed Taktovka tower for the 100th time…

Yes, that’s the way I wanted to celebrate it. To clarify – it wasn’t exactly on the date of my birthday but some five or six days from that.

What makes Taktovka so special to you that you climbed it a hundred times?

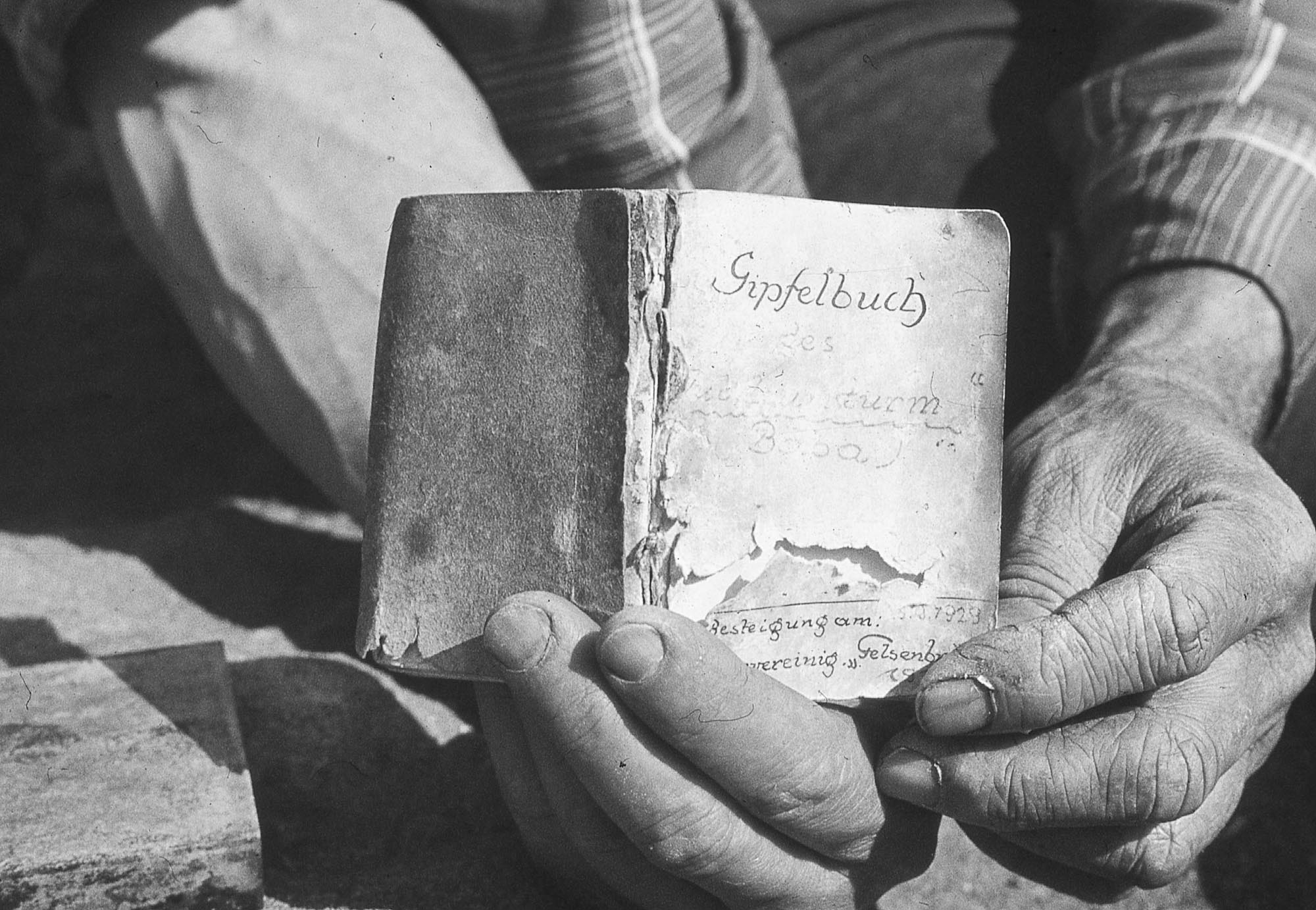

First of all, it is a beautiful rock. Really beautiful. I climbed it for the first time in 1944, I somehow clung to it, and since then I was always coming back with my friends. I have it noted down – all the dates I climbed the tower, the friends who joined me and so on… I keep my records of the ascents to that tower up to my 50th birthday. Then I stopped noting it down because I haven’t been climbing too much. I have only been to Taktovka about ten times since then, I kept climbing it to my 70s. It is the most beautiful tower to me.

What are you most happy about?

Today I really appreciate one thing – that I was so lucky to spend my whole life in the group of my fellow climbers who had “the same blood type”. We got along so well. Today, only Drahoš Machaň is left of that group. I consider it to be such a gift to be growing up among such great people. We always helped each other – we even built cottages together. These cottages still stand and are used by our children and grandchildren. I’m happy that I’ve had such good pals around me my whole life. Only few are that lucky.

Just as Bogan stays with us in Skalák forever…

__________