MEISTERWEGS

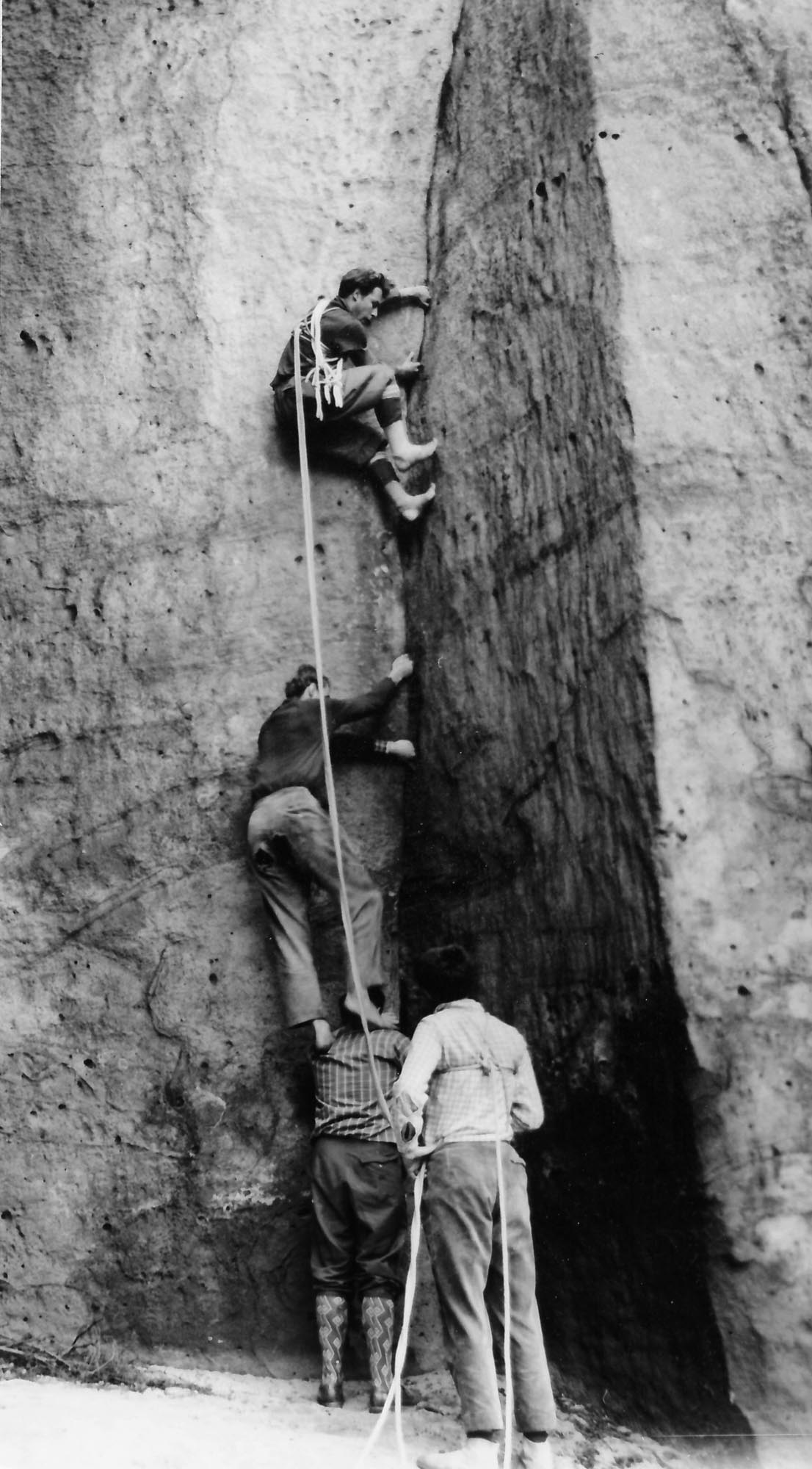

SO YOU WANT TO GO TRAVELLING WITH THE NATIONAL TEAM? THEN GO CLIMB SOME DEATH ROUTE. IF YOUR TRUSTWORTHY GUARDIAN ANGEL STANDS BY YOU, HE MIGHT HOLD YOU ON A SLIPPERY FOOTHOLD IN THE CRUX AND YOU MIGHT GET FROM BEHIND THE IRON CURTAIN FOR A WHILE. IF NOT… YOU GO STRAIGHT TO CLIMBER’S HEAVEN. ONCE YOU CHOOSE, THERE’S NO RETURN…

FIRST VAGUE OUTLINES

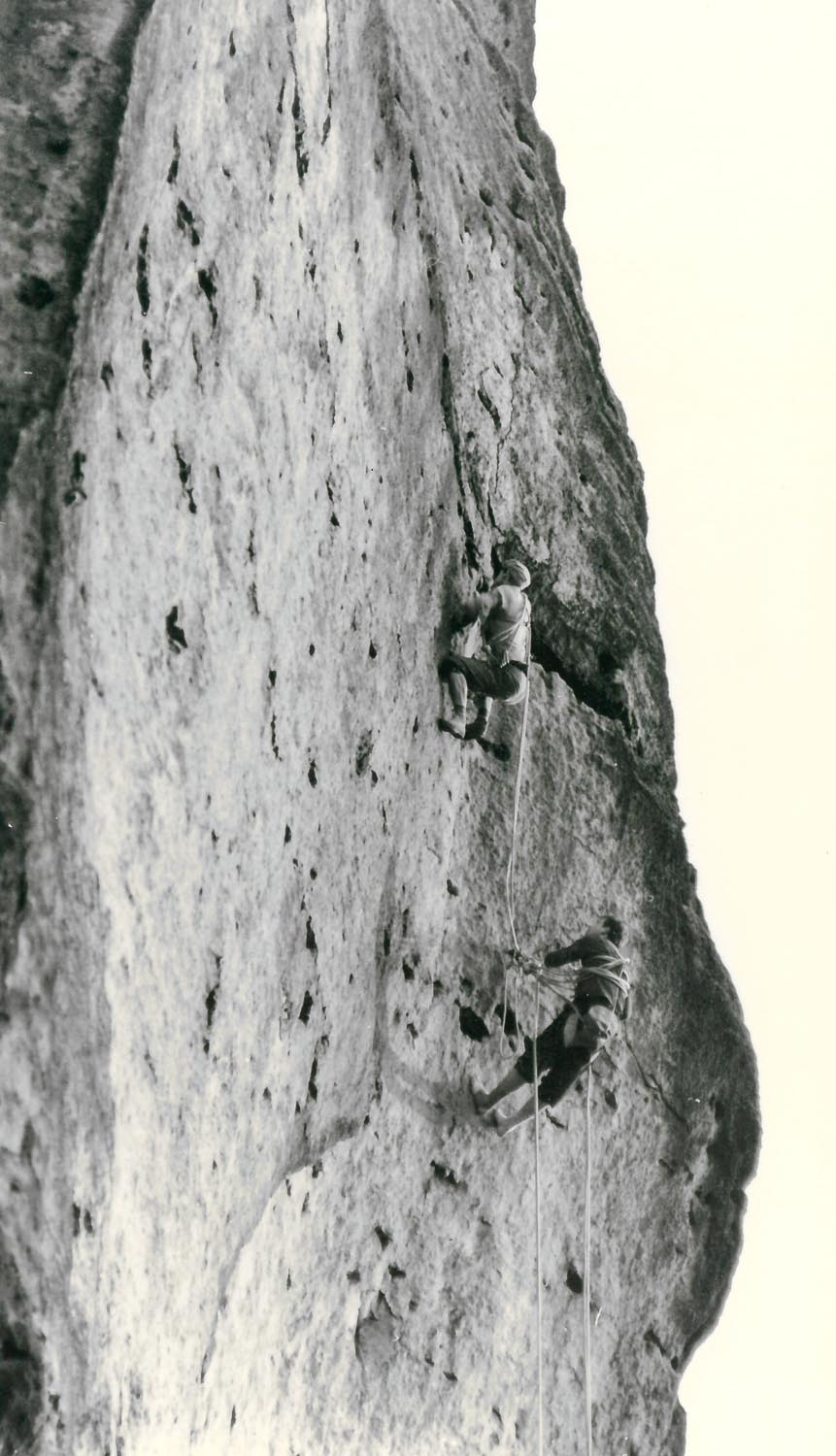

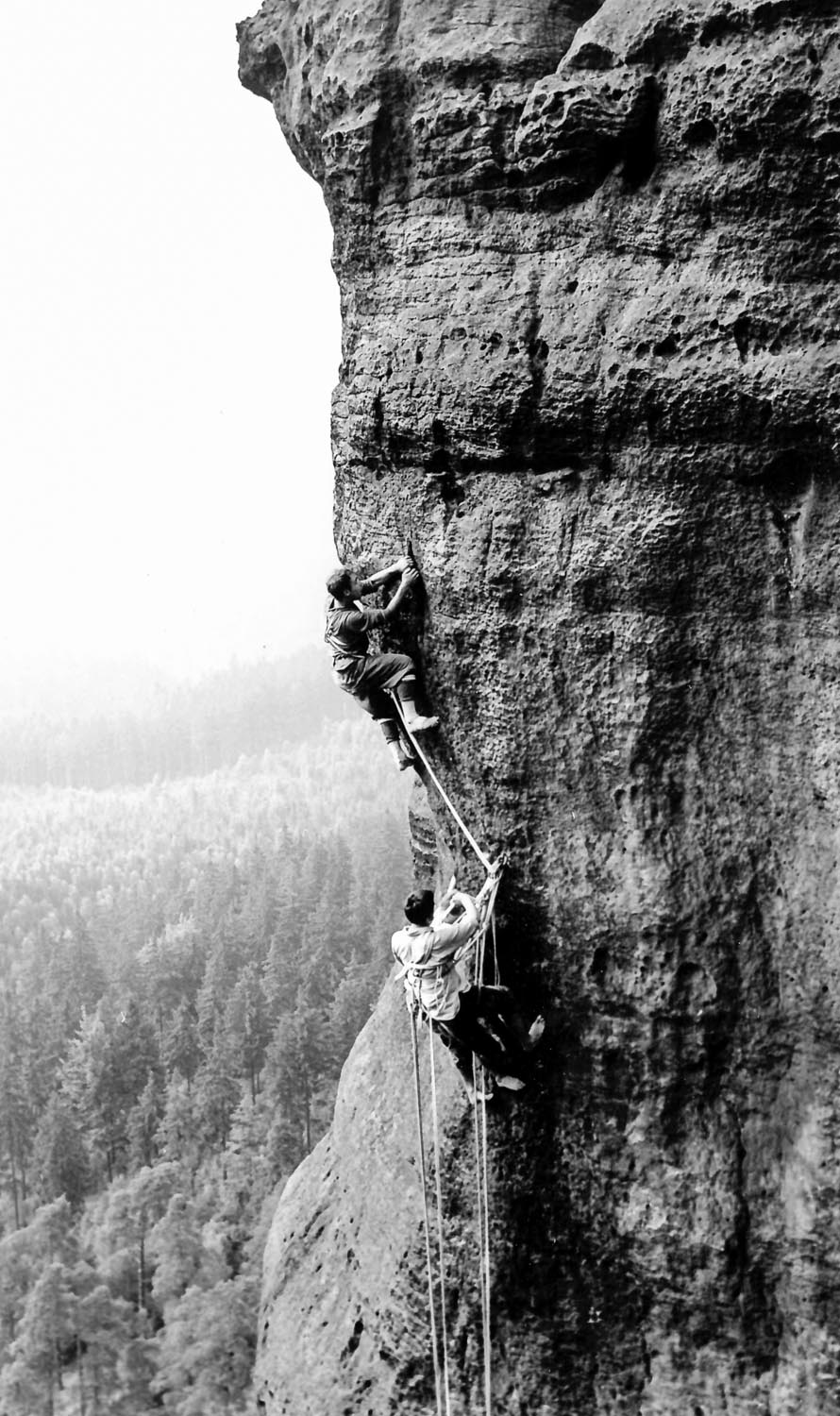

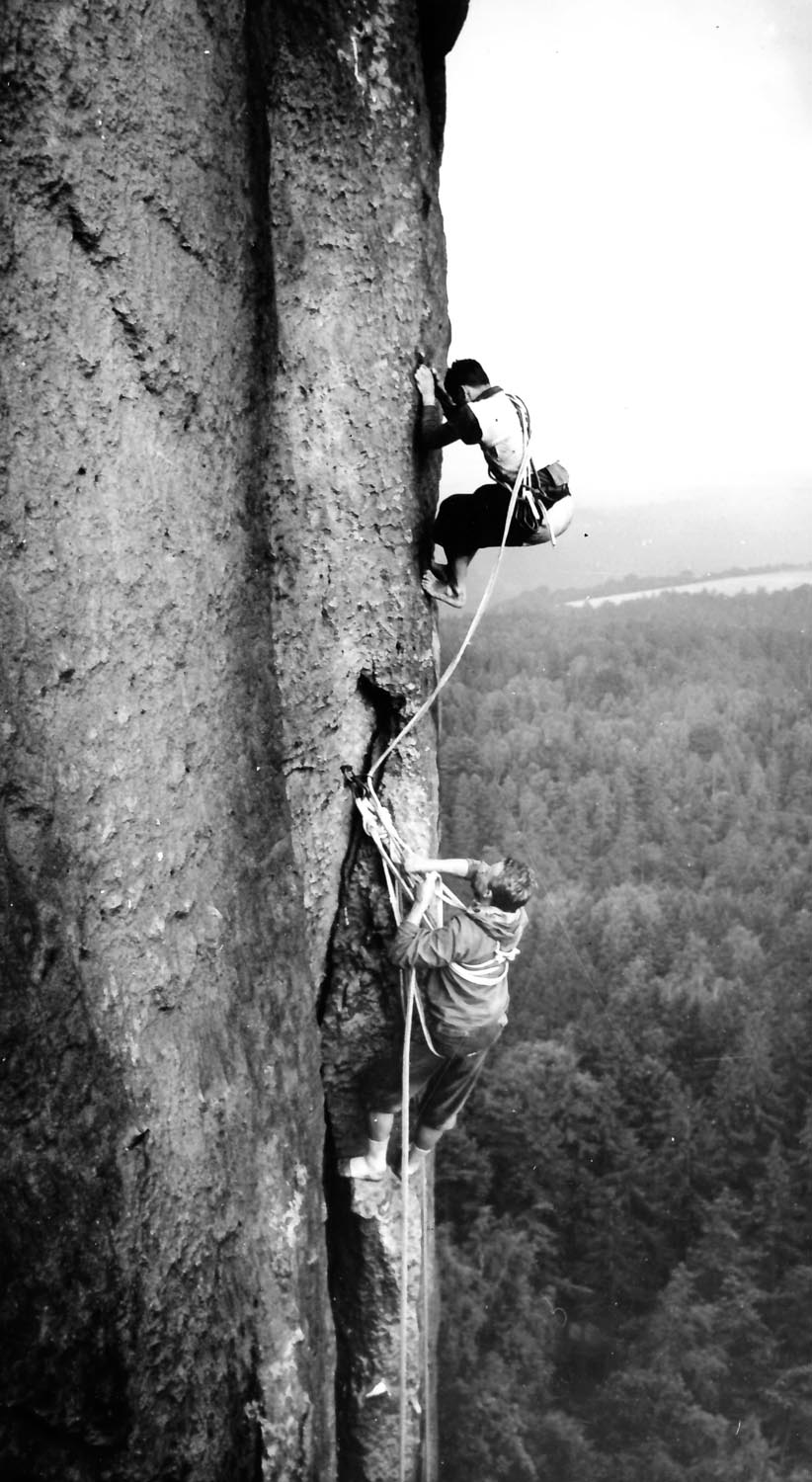

The longer I was part of the sandstone climbing community in Saxony, the more often I stumbled upon the term “Meisterweg”, translated as “the master’s route”. Mostly, I would hear the word from a seasoned sandstone climber pointing at some blank wall or an overhanging corner, or when he was nodding his head on your spiced up story about a route you had tried the other day and almost took a grounder in a crumbling section below the first or second ring. At first, I didn’t even know what to imagine under this term.

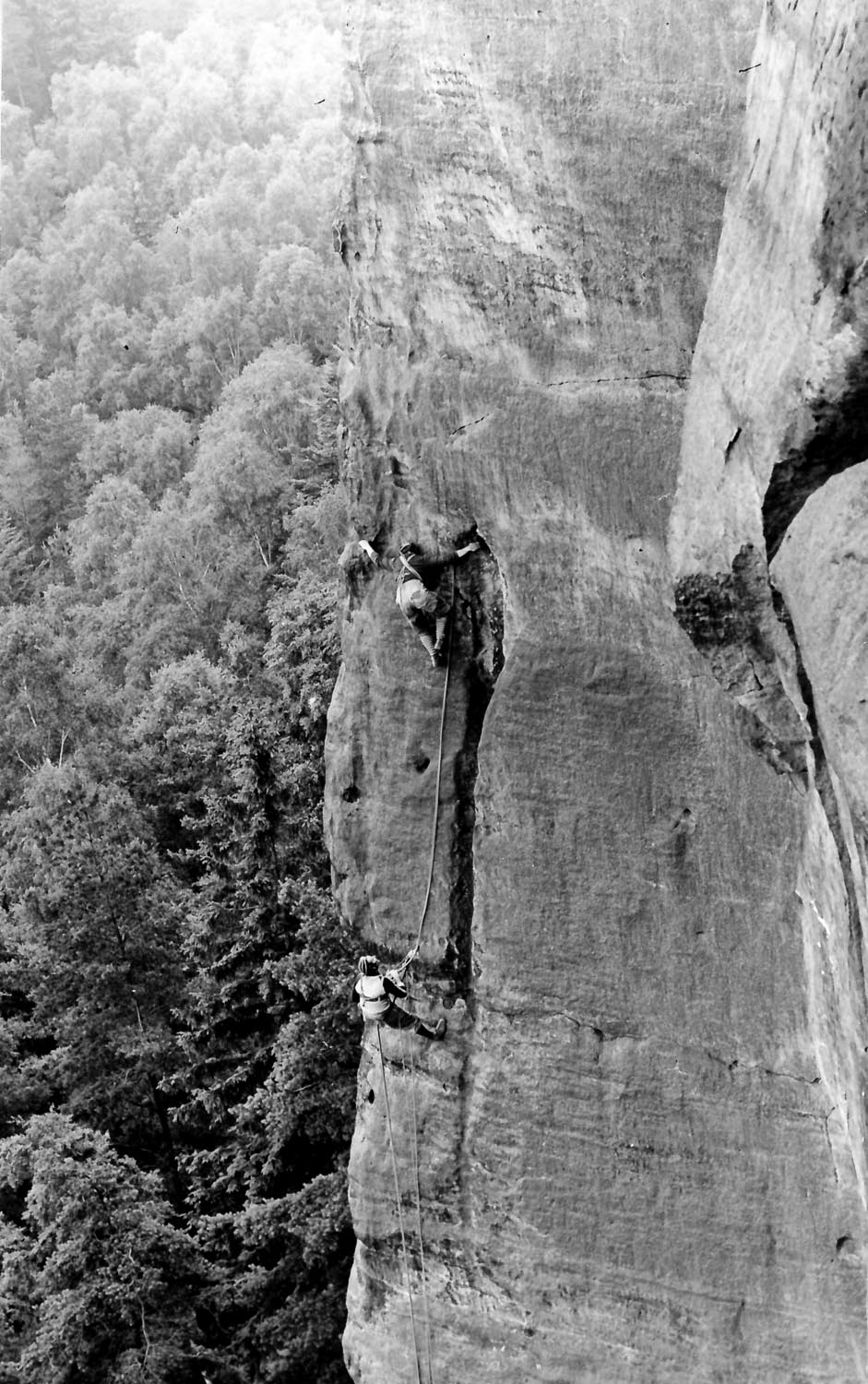

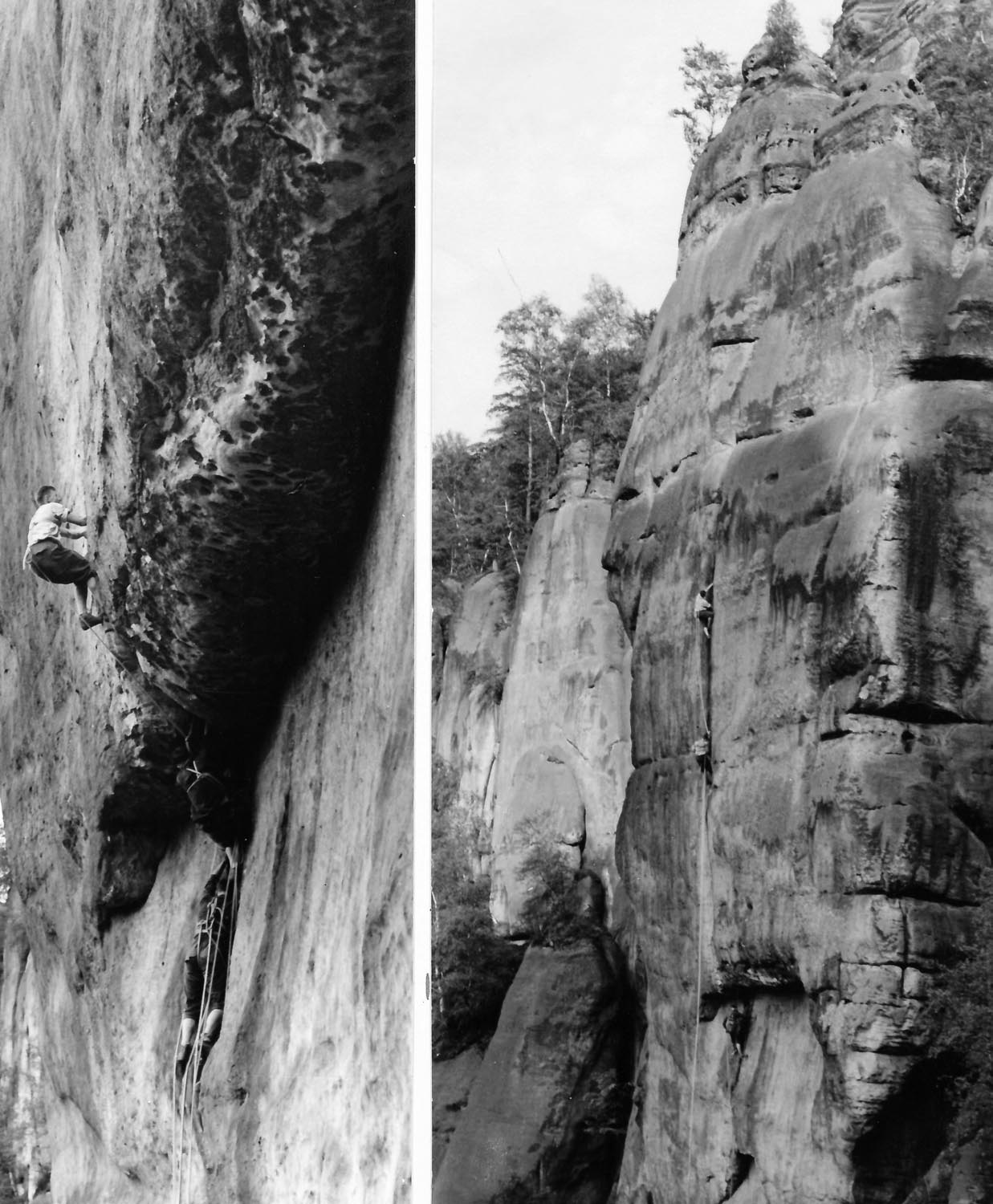

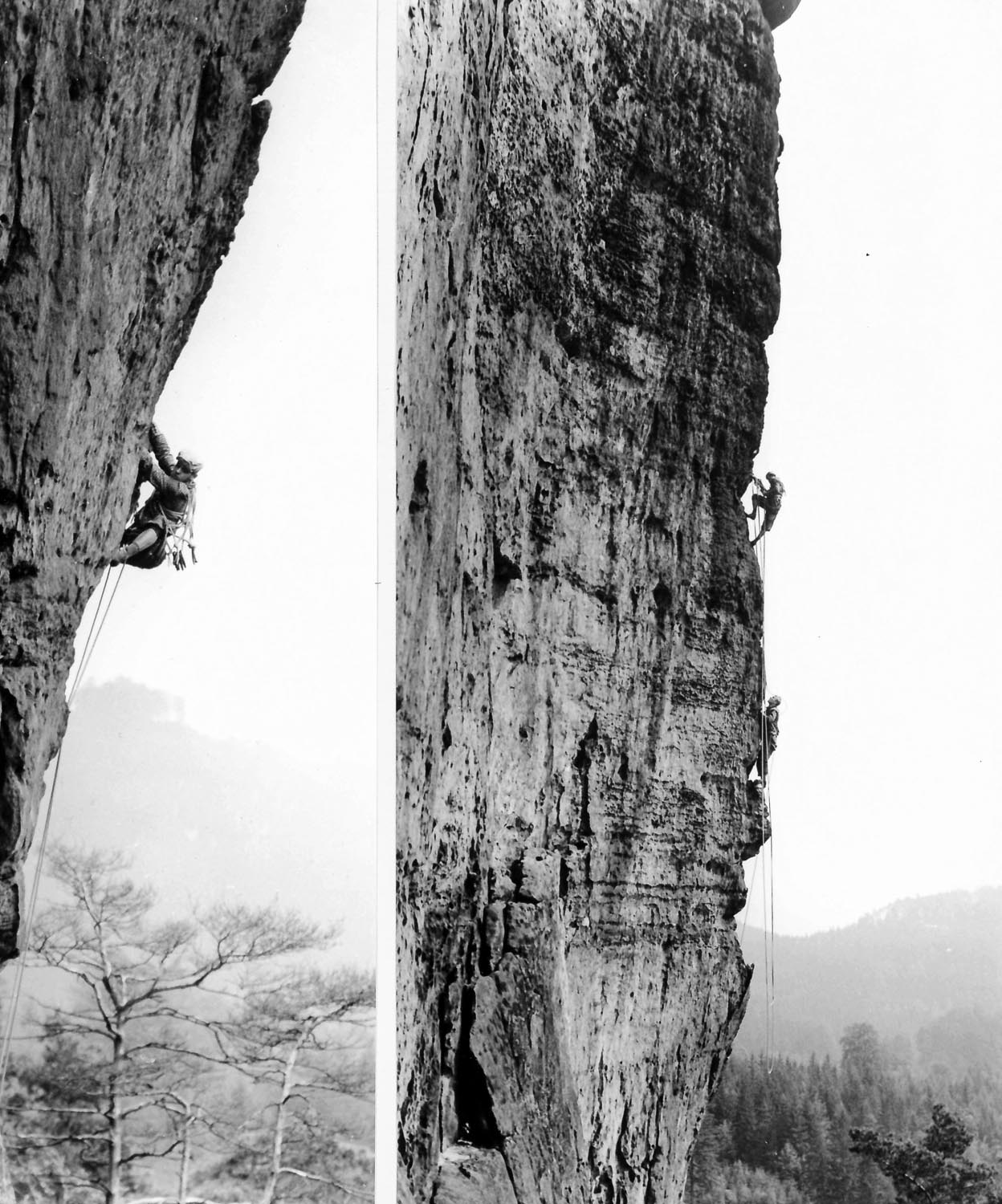

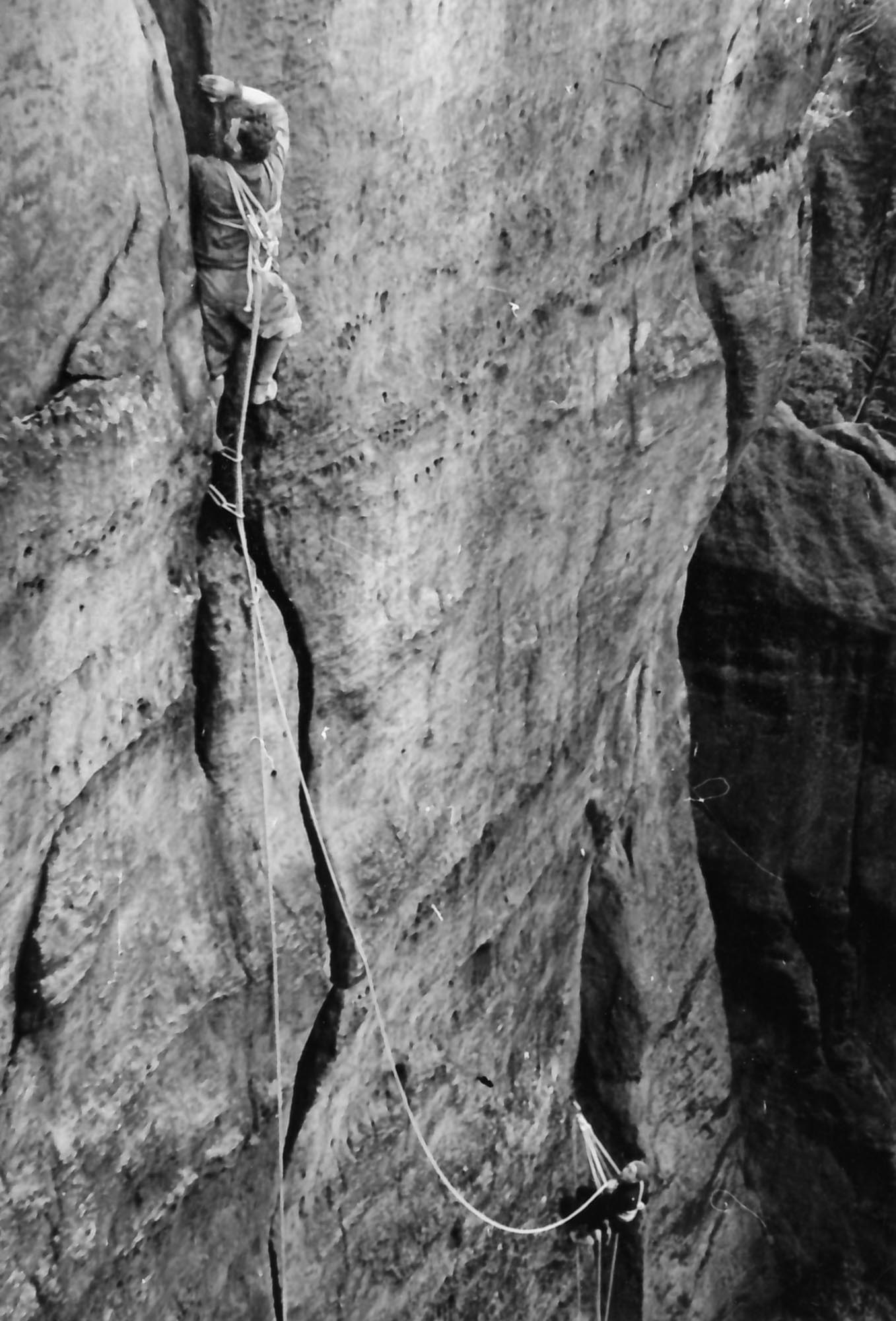

One thing was clear though – these routes always count among the epic lines, they certainly aren’t the easiest ones, and you couldn’t say that they are overprotected either. In fact, the rings in these routes are usually so far apart that you could consider them to be more of waypoints that could help you with the direction of the route, or anchors, at which you could divide the route into several pitches once the rope is pulling on you so much that it threatens to rip your harness apart.

But who determines, which route is worthy of the master’s label and which is not? Is it enough that an enthusiastic survivor of the route starts spreading the news that he’s found a new one? Is it a general label for routes that pose both technical and mental challenge? Or are there any clear criteria and a definitive list of these routes? What does the name Meisterweg actually mean? To answer these questions, we will have to venture a few decades back and look behind the iron curtain.

WILLKOMMEN IN DER DDR

Welcome comrade! Maybe you were born later, maybe you forgot, so I’ll give a very short history lesson first. DDR (East Germany) was a typical Soviet dystopia.

The beer was cheap. At least, when it was available… quite often though, it wasn’t. Sometimes, in the summer, the shelves with drinks got empty – no beer, no water. So you had to drink the disgusting tap water. In case you wanted to be fancy, you coloured it with some syrup containing questionable ingredients.

The food situation was even worse – you couldn’t get much good meat because anything worth it was immediately sent to the West to make at least some money. The bananas were so rare that people waited in long queues for them (in case there were some in the first place). When there weren’t any bananas, there was a queue for something else. Fruits and vegetables? Today, people complain that there’s too much chemicals in them. It used to be different. Often, there were no vegetables or fruits at all.

Moreover, the offerings were much smaller than today. A few apples, a few lemons, sometimes those weird Cuban oranges that were so bitter that you could use just their juice, and of course the potatoes – that’s it. Today, you hesitate if you should pick red, sweet, boiling, baking, or salad potatoes. Back then, the only question was to buy or not to buy them. Large amounts of veg and fruits harvested during the summer had to be pickled to have at least some choice during the bleak winters.

It was a golden age for under the counter shopping. The most wanted goods didn’t even get to the shopping windows. Instead, they were bartered with the more influential and lucky customers for some reciprocal service. A head of a car workshop could offer spare parts, a principal of a higher-level school could help your kids to get there, a bike mechanic could get you a brand new Favorit, and friends helped friends. But ordinary people had to face empty shelves or prepare to pay an outrageous price. Often, though, there was not much to pay with.

The streets were full of smelly cars with two-stroke engines such as Trabant or Wartburg. Rarely you could see a “fancy” import car such as Dacia, Lada or Moskvitch that was so thirsty, it could only take you on a trip from one gas station to the next one (and you still better carried some extra gas canister just in case you didn’t get there). The waiting line for such a scrap could take up to 20 years. And its price was astronomical.

Phone? Forget cell phones. Here and there, you could find a phone booth. Dialing a number required rotating a kind of wheel with a finger hole for each number. If you were a climber, you often had to use your little finger or a pencil to dial because your fingers couldn’t fit the holes. Those who had their own phone at home were either members of the secret police or were eavesdropped by them.

You didn’t even have to go abroad. I mean, you couldn’t. Except for “friendly” countries; if you were lucky. At each state border, you had to stand in line for several hours. As a reward, you could go to touristy places like Lake Balaton, where you had to wade through a half-mile of shallow water before the water rose at least up to the waist and you could swim. You could also go to the Baltic Sea where the water was so icy that the self-preservation instinct prevented you from venturing into the water deeper than your knees.

There was no real freedom. Your life and fate were not in your hands – they were ruled by reports written by people from the communist party, whom you had never met. I wouldn’t call it good old times but rather a dark part of our history that should stand as a lesson. And from which we should learn.

_

_

BUILDING THE BODY CULTURE

But what does that have to do with climbing? Almost anything in the states under the Soviet rule ran according to so-called central planning. The building of large blocks of flats, automotive industry, united agricultural cooperatives – the five-year plans had to be fulfilled regardless of the reality and demand. They planned, produced, and when there was too much of it, they simply threw it away. The missing products weren’t made because the plans couldn’t be changed. In many ways, we lived in a purely absurd reality. Even sandstone climbing became somehow planned and controlled.

Relatively soon after the end of the World War II (around 1953), East Germany started following the Russian example and aimed to establish formal sports ranking for the climbers. They even supported this bizarre idea with an ideological argumentation that such a ranking could reveal the real value and performance of “our” socialist athletes and help us to get an international acclaim. Following the ranking system, the state could devise a plan that would develop the climber’s performance, educate the youth, and build the overall socialist body culture as well as support an individual’s enthusiasm to work and defend peace. In short, however absurd the proposed system was, it was ascribed with an immense political importance.

Anyway, soon it became clear that climbers back then weren’t so different from today – they were certainly not happy to welcome such measures. With a few exceptions, almost no one volunteered to participate in the program. In logbooks on top of sandstone towers, you could sometimes even find such ideological exclamations as: “A climber has to protect peace and build socialism!” Of course, climbers did not hesitate a single moment and added mocking notes such as: “A climber doesn’t have to do anything at all.”

The bitter political situation in the post-war years was actually the final straw that made many of the top climbers leave East Germany. Among them was Karlheinz Gonda, Dietrich Hasse, Harry Rost, and Herbert Wünsche. They went to the West, lured by the big alpine walls, blooming meadows, and most importantly, by freedom.

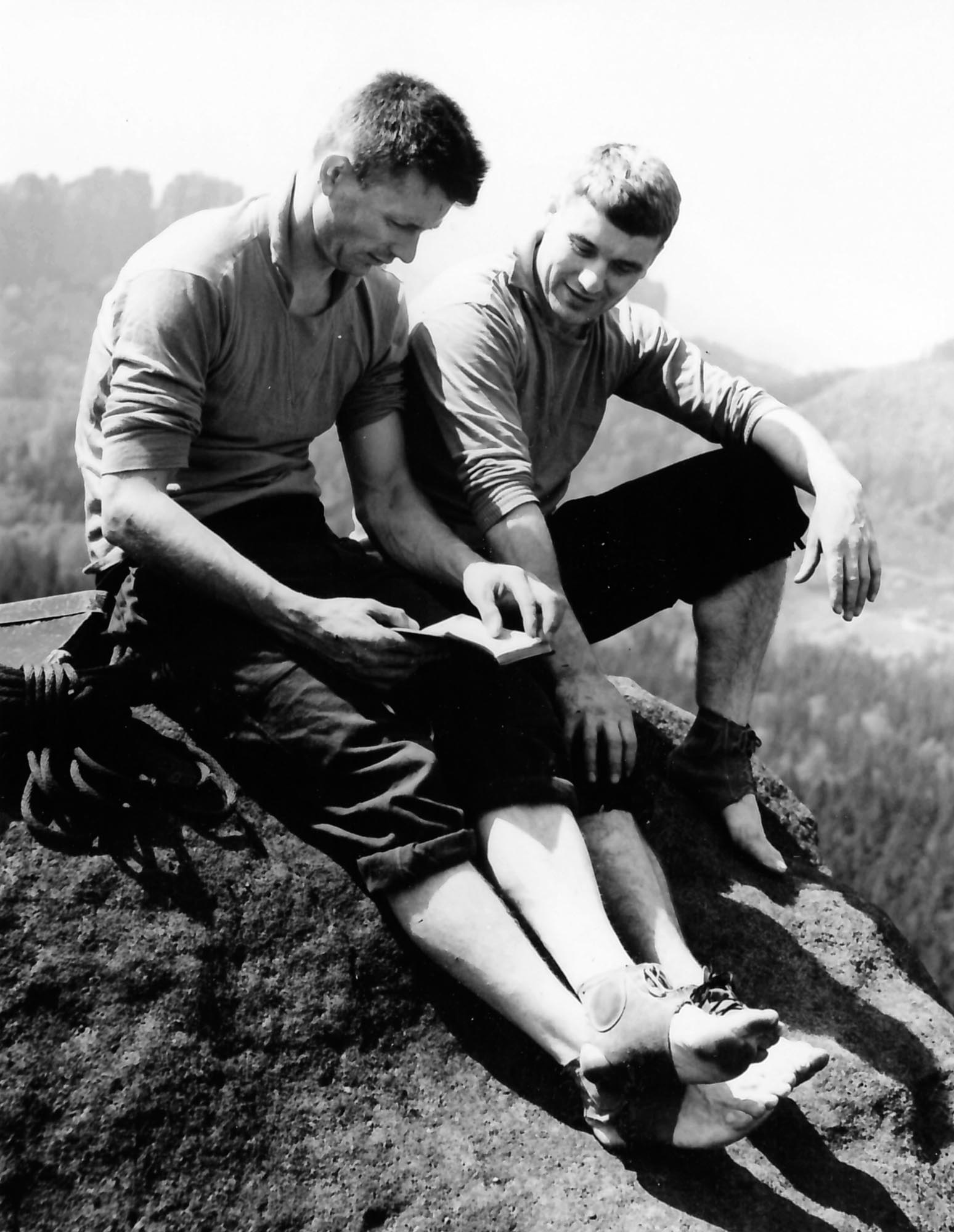

But let’s get back to East Germany. The proposed ranking program had to involve as many athletes as possible. And according to the customs of the USSR, where reason failed, the force was used to solve the problem. So in 1958, the sly officials put their heads together and came up with a clever solution. From now on, the vacant spots in climbing expeditions to the Caucasus and the High Tatras were reserved only for those who deserved them by being obedient to the Soviet Union, and who achieved a certain performance rating. And that was it. Anyone who wanted to climb abroad had to get involved. And since in 1961, the highlight of East German functionalist architecture, known as the Berlin Wall, was built in a single night, the possibility to travel became quite limited. Suddenly, everyone wanted to get the chance to climb abroad.

THE MASTER OF SPORT

The term “Master of Sport” first appeared on the East German climbing scene in 1957. By 1960, five obedient climbers had reached the master rank, and in 1961 they were joined by the first woman. Let’s be honest – it wasn’t so hard to fulfil the criteria. Actually, it was quite the same as getting a driver’s license in Egypt (the story goes that you only have to drive 15 m forwards, 15 m backwards, and honk). You only had to climb 10 routes of grade VII (approx. f5b) and the rank was yours. Although the classification was still closed back then and grade VII could mean anything in between 5b and 6a (or even harder), you can hardly consider such an effort to be a proof of real mastery of the discipline. Even this system was about to change though.

Another turning point came when officials put their heads back together a few years later and figured out how to divide climbers into several performance classes according to relatively simple and fixed criteria. You know, Germans tend to like order. The more difficult routes you climb, the better the performance class you fall into, and the more privileges you get. Suddenly “The Master of Sport” became the highest rank you could achieve. How?

MURDER, THEY WROTE

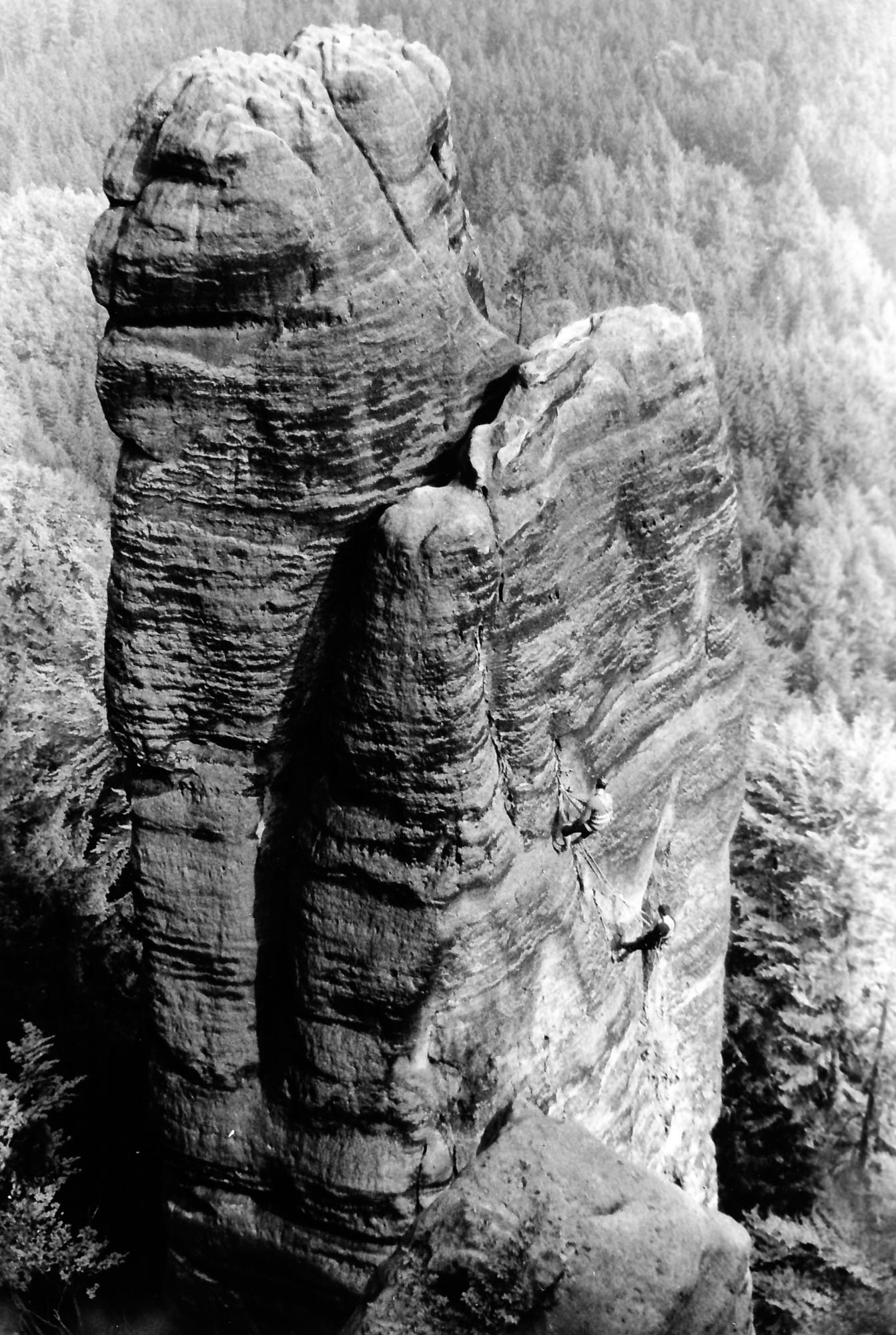

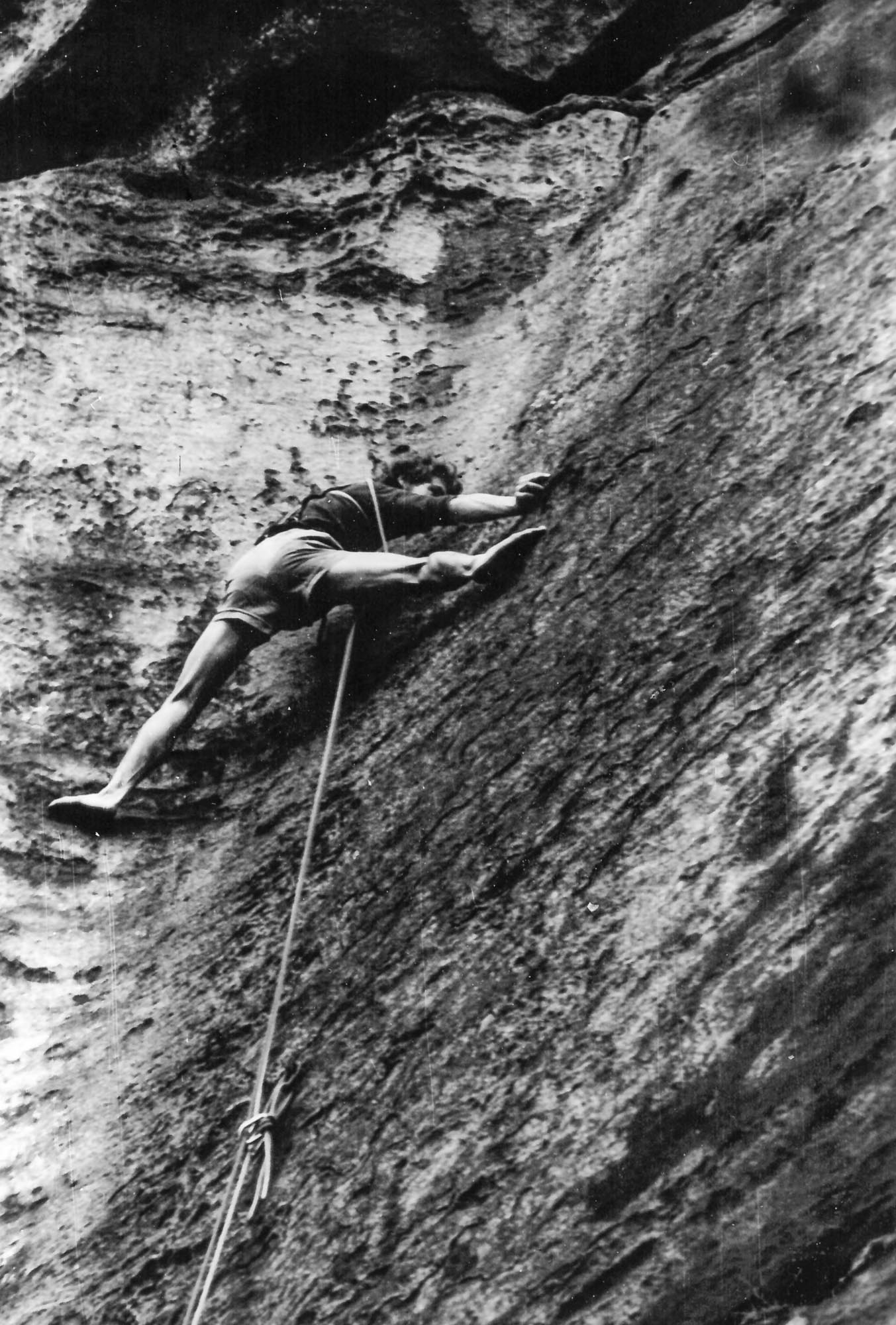

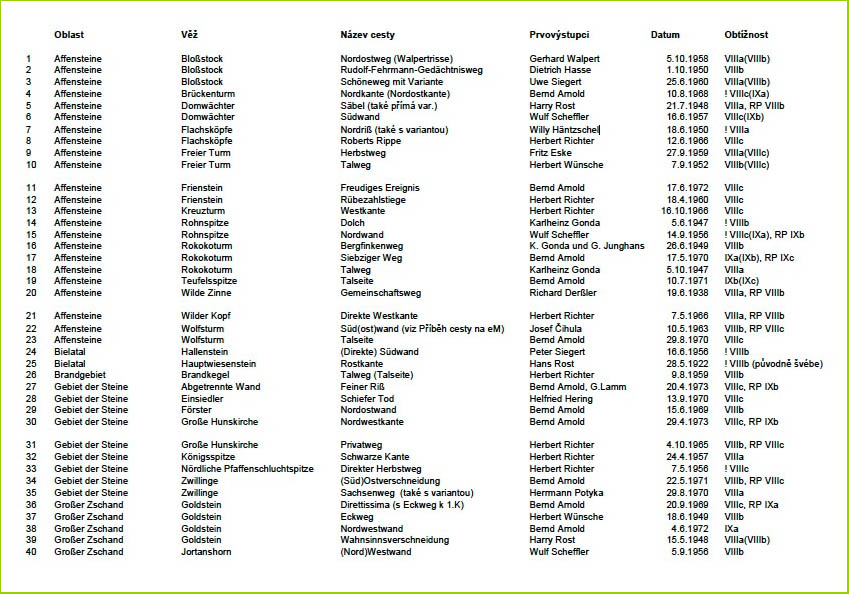

They simply compiled a list of the most difficult sandstone routes in Saxony. And when I say the most difficult, I must add that it was not only the absolute difficulty of climbing moves, the length of the route, and its monumentality that counted but that the mental difficulties were also understood as an important attribute of the route at the time. This is then the story behind the list of legendary routes which did not lose much of their magic – they are still scary enough to make your hair turn grey. Once the list was made, these lines got a new label: “VIIcM”.

The rules of the climbing association included the exact number of such routes that you had to survive before you became a true master of the sport. That’s the origin and true meaning of the Meisterweg phenomenon. The Master’s routes are simply the lines included on this list. The Meisterweg selection was updated every year – mostly, routes were added, and only rarely, they disappeared from the list. The list was last reviewed in 1974 and the final version of the Meisterweg menu offers 92 tasty lines.

“A typical Meisterweg route offers an extraordinary experience.”

Stephan “Seppo” Gerber

If you are wondering who chose the routes, ascribed them with the adverb “Master’s”, and regularly updated the list, it was the boys and girls from DWBV (Deutscher Wanderer und Bergsteigerverband group, established in 1958). DWBV was originally a hiking and mountaineering organization which, in 1970, included orienteering runners as well and thus got renamed to DWBO (Deutscher Verband für Wandern, Bergsteigen und Orientierungslauf der DDR). This club was a precursor of today’s climbing association.

SILLY IDEAS ARE CATCHY

Although it didn’t seem so at first, this system of ranks and performance grades gradually gained popularity among East German climbers. As the saying goes, one can always find a bright side of anything that happens – it all depends on perspective. It’s a good thing to find some balance between sense and emotions. With the ranking system for climbers, it was no different. For the young and ambitious climbers, it became a huge source of motivation which could lead them to a tangible achievement. For the older seasoned climbers, it provided a chance to get into the narrow national team and climb in the big mountains abroad. And for everyone else, it was an opportunity to track their progress year after year and get from the local climbing club all the way to the national elite.

“Are you bored?

Are you fidgety?

Do you have ants in your pants?

Or do you want to touch a piece of history?

Then climb a Meisterweg!”

CLIMBING CASTES

Outside of the youth category, there were four different performance ranks for adult climbers established in 1967. If you wanted to get the rank, you had to complete the required criteria in a single year. Do the grades seem easy to you? Don’t forget that the old “closed” grading system was somewhat treacherous – certainly, not all routes graded VIIc were created equal (some of them became the stuff of legends and even today, nobody wants to climb them).

3. PERFORMANCE RANK – required leading 10 grade V routes (approx f4b) of your own choice.

2. PERFORMANCE RANK – required leading 10 grade VIIb routes (approx. f5c), at least three of those had to be cracks.

1. PERFORMANCE RANK – required leading 12 grade VIIc routes (approx. f6a and harder), these had to include a wall, a slab, a handcrack, and an offwidth.

MEN MASTER’S RANK – required sending 12 lines graded VIIcM from the list of the selected legendary Meisterwegs. Again, these had to include a wall, a slab and crack climbs.

WOMEN MASTER RANK – lead five VIIa routes and five VIIb routes of your own selection.

I have to stress once again that the classification system was closed – VIIc was the hardest grade and even VIIb included some bold lines that could surprise even today’s climbers.

The routes are still there, even 40 years after the last update of the Meisterweg list, these legendary bold lines are waiting for you – will you answer their call and come to Saxony? They are as appealing as intimidating. I dare to say that even among locals, you cannot find many of those who have climbed at least half of them.

__________