CHONGO CHUCK

The verdict was clear: “You’ve spent too much time in Yosemite.” In 2005, climbers filled the courtroom to support their beloved guru. Still, the pioneer of slacklining and developer of bigwall techniques was evicted from his home. Where is he in 2022?

FEED THE CAT

I traveled to Yosemite in May with my close friend and climbing partner Alena to catsit. It was the ideal excuse to live near the Valley for a month – work in the morning and spend the rest of the day on the granite walls. Cameron, a local photographer, writer and an aspiring highliner, messaged me in January that he and his girlfriend were looking for someone to watch their house and feed Tulip the cat while they went on vacation to Utah. Cat and Yosemite? It didn’t take long to convince me and Alena was just as quick to join.

We decided to climb Half Dome on our first day in the park. Why prolong the inevitable? Waiting would only mean more hikers and climbers sharing the Valley. There was only one major disadvantage to climbing the Dome before the start of the season: a more challenging descent. Instead of the relatively comfortable wooden stairs accessible during the summer season, we made our way down the dramatic backslope of the Dome on two heavy steel cables, using prusiks for safety. Had we waited one more week we would have seen Alex Honnold showing Yosemite Valley to his newborn daughter June from atop the iconic 2696m cliff.

“Do you think we’ll see him? Alena asked me. We had heard Alex was in the Valley that week and social media was abuzz. We, along with surely every other climber by now, had been asked 150 times or more, “Have you seen that climbing movie? Free Solo? You should totally see Free Solo!” Don’t get me wrong, we both like and admire Alex and would love the chance to meet him. But Yosemite has been host and home to thousands of incredible climbers over the years. Given the choice, we agreed we’d rather meet one of Yosemite’s less high-profile legends; a man shrouded in so many myths that even he himself may not know what actually happened and what the climbing folklore made up. But in his words, “Everything is relative,” so what is or isn’t true doesn’t really matter to him. The man is known as Chongo Chuck.

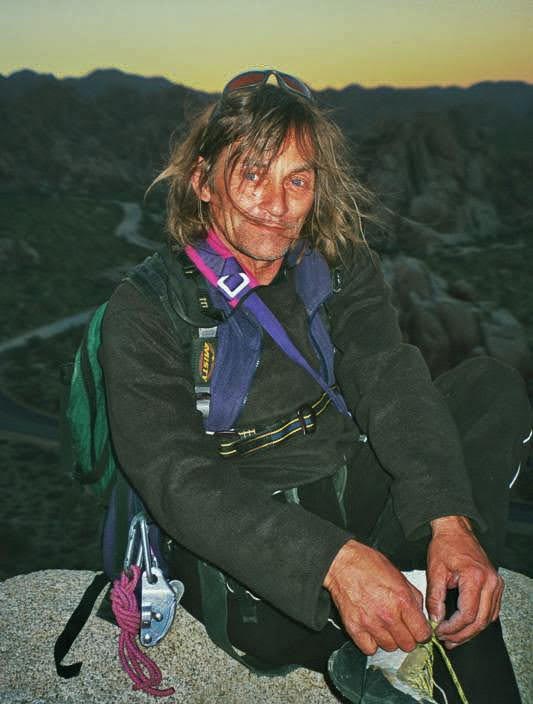

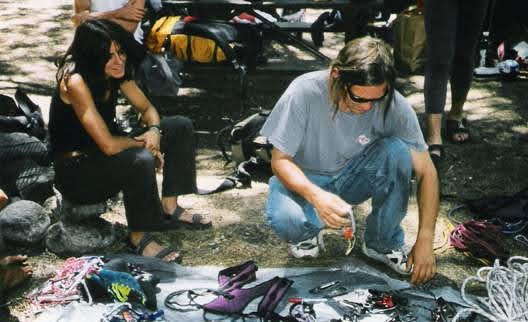

(photo: Dean Fidelman)

CHONGO CHUCK, THE YOSEMITE LEGEND

Charles Victor Tucker III, known to most simply as Chongo, spent a big part of his life in Yosemite where he was cherished as a local slackline and climbing guru for many years. Tommy Caldwell compared him to Master Yoda from Star Wars. He prides himself on having trained and galvanized many world-renowned slacklining pioneers. He lived outdoors for most of his life where the forests and caves of Yosemite Valley were his home. Chongo declares with great pride that he has been ‘homeless’ all his adult life. But Chongo isn’t necessarily homeless, he’s just houseless, which is a big difference. Nature is his home, and as he says, “When you’re a climber, you’re homeless anyway, you’re always running around from one climbing area to another, camping out in order to be at the place you’re gonna climb at… I guess you could call that homeless.”

Over the years Chongo has been dubbed the godfather of slacklining, father of big wall climbing, and above all, a spiritual leader. Although Chongo never matched the giants in his free climbing ascents, his techniques for big wall climbing were revolutionary. He devised complex equipment and methods that allowed him to virtually hitchhike the entire face of El Capitan. “He had all these systems where he could haul all these massive loads with these multipulley systems he had made up… Just stuff to live on the wall for an indefinite time period,” professional climber Steph Davis said in the article by Michael Brick. Once, he took three days off in the middle of a two-week sojourn up El Cap to solve some half-forgotten existential riddle. Chongo wrote down his unique inventions, tips and experiences in The Complete Book of Big Wall Climbing, which, at 576 pages, is the most comprehensive manual on the subject in existence.

Chongo, the “Monkey Man” in Spanish slang, received his nickname after the sticky soles he once made from Mexican rubber to use for climbing. He later repaired climbing shoes for other climbers in Yosemite and, as with most of his endeavors, the value of his work was appreciated by those around him. Chongo started climbing as a self-taught teenager in California. He was born on an American military base in Japan, and, according to his own words, he still remembers the fear he felt during his birth (according to our calculations, the year was 1951 – editor’s note). His father was a civil engineer and Chongo was the eldest of seven children. He graduated high school in Los Angeles and then spent a year studying undergraduate mathematics at the University of Arizona.

Throughout his life, Chongo made a living as a computer programmer, writer and journalist. In addition to repairing climbing shoes, he designed and sewed his own brand of clothing. He was so successful that in 1995, rangers began prosecuting him for running an illegal textile business out of his tent in the Hidden Valley Campground.

Chongo is fluent in Spanish, having lived in Mexico for eight years. He settled in one of the most dangerous parts of the capital, in a colonia that even many Mexicans shunned. Chongo said the local narcos respected him much like the climbers in Yosemite. But then, when he was smuggling weed across the border, he was shot on the US side and imprisoned for several years and any confidence he may still have had in the capitalist society was gone for good.

“When he was smuggling weed across the border, he was shot on the US side and imprisoned for several years and any confidence he may still have had in the capitalist societywas gone for good.”

Above all, Chongo loves writing, which he can take with him anywhere he goes. He has published an incredible range of books, from practical guides on big wall climbing to philosophical treatises to a fictional novella and scholarly physics studies, including one of his best-known titles: The Homeless Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics. (You can find his collected works on his website ChongoNation.org – editor’s note) In his words, it was quantum mechanics that brought him the most pleasure as soon as he was able to understand it. It helped him “answer all the questions about nature in an absolutely wonderful way.” Since then, Chongo has been fully absorbed in studying and writing about the leading edges of physics and he has even started collaborating with a leading professor from Stanford University. All told, the details of Chongo’s life would feel at home in a Hollywood biopic, the kind of story that’s just wild enough to be true.

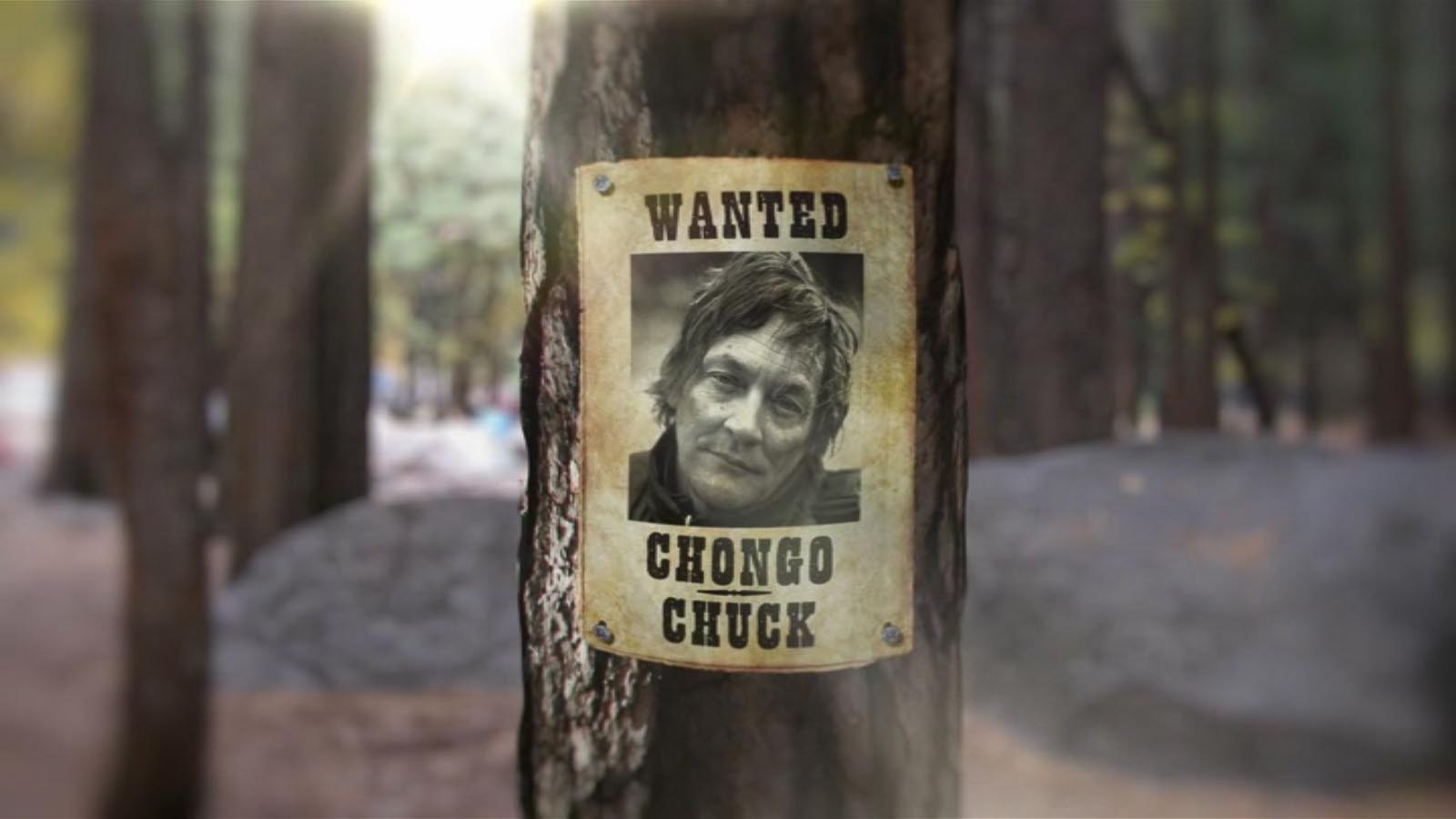

Alena and I had indeed seen Free Solo, along with any number of Alex Honnold’s appearances on social media, interviews, articles, internet videos and other films, but we knew only enough about the elusive Chongo to want to know more. As a highliner it would be an honor to meet the progenitor, but I could only imagine the treasure trove of stories he would carry with him. To be honest though, we weren’t sure at that point if he was even still alive. The latest we’d heard was about his eviction from Yosemite. He’d lived there for over a decade until finally the park authorities decided to crack down on the climbing community, with Chongo as a target of special interest. However, no one knew the Yosemite forests better than Chongo, and the rangers were unable to track him down. After a year of unsuccessful searching, they issued an arrest warrant. Climbers filled the courtroom to support their guru, but were unable to overturn the verdict. In 2005 Chongo left Yosemite and relocated to Sacramento where he slept under a grey concrete bridge that couldn’t be further from the green woods and granite of the Valley. Almost 17 years have passed since then. What has become of Chongo in that time?

IS CHONGO STILL ALIVE?

Later, while resting after the exertions of Half Dome, I googled Chongo’s name. The very first page referred me to the Mountain Project’s live forum where climbers try to answer the same question I had been puzzling over: “Is Chongo still alive?” Unfortunately, I couldn’t tell from the discussion where Chongo was at the moment, but it looked like he should still be among the living. I learned that after moving out of Yosemite, Chongo wrote for a homeless newspaper in Sacramento. He slept outside and then spent his days writing in the city library. The most recent messages on the forum are from November of the previous year, when some climbers met Chongo in his favorite spot in the Hidden Valley Campground in Joshua Tree. He was selling his books there and entertaining climbers with stories. Only a few months earlier, he did the same thing in Smith Rock, Oregon. Well great, Alena and I were headed to Smith after Yosemite so maybe our wish would come true after all. Still, we agreed that the chances were minuscule and from then on Chongo came up only in connection with my regular slacklining routine, where one of the methods for standing up on the line bears the master’s name. (See video – editor’s note)

Still, there was a part of me that wanted to take a trip to Joshua Tree. What if Chongo was there after all? Maybe then I would get to experience something similar to Dean Potter, for whom Chongo opened the door to the world of slacklining in 1993. Dean describes his first meeting with Chongo very colorfully. He spotted him on the line, surrounded by hippie climbers and desert bums cheering him on. Energy emanated from him and the desert suddenly seemed full of life. Dean changed his mind about his early departure and the next day, he gathered the courage to sit next to Chongo who gave him a crooked smile and egged him on with, “Try it, it’s bitchin’!”* And so began Dean’s slacklining career. Like other pioneer slackliners, Dean Potter owed it to Chongo.

* (The word “bitchin‘” is impossible to define. Chongo explains in the glossary at the end of his book Love and Hate at Sea: A Book About Wall Partners: “Bitchin is among those rare words – perhaps the only word – that can only be defined by itself, owing to the fact that there is simply no truly precise equivalent” He then adds a “scientific definition” of the word as “meaningful, logically consistent, and physically true”. Put simply, only a few people deserve to be called “bitchin’” and it should be taken as the highest honor. For those striving to be bitchin’, Chongo wrote a manual titled How to Be Bitchin, author’s note)

Scott Balcom, the slackliner who made history with the first-ever highline send on Lost Arrow Spire in July 1985, also met Chongo in Joshua Tree. It was in the early 1980s when Chongo was only 29 years old. But Scott already looked up to him as the experienced adventurer who introduced him and his buddy Darrin Carter to climbing. At this point Chongo was crashing with a friend in Hollywood while working as a programmer in LA, and he would regularly take Scott to the rocks in Joshua Tree in exchange for a ride. When they went to Yosemite, Chongo introduced Scott to walking on the parking lot chains: a standard activity among the local climbing community at the time, from which modern slacklining was born.

After Scott, Darrin Carter was the second person to send the Lost Arrow Spire highline and in June 1995, ten years after the first ascent, he became the first highliner in history to free solo it. Of course, Chongo was part of the team on the tower that day as Darrin’s mental support crew. Darrin’s proven method of getting himself fired up was to bombard Chongo with curses. He yelled at him, “You piece of shit!” which seemed to work. “Those who have to really work become true masters. Naturals rarely learn to keep trying,” Chongo says.

“Those who have to really work become true masters. Naturals rarely learn to keep trying.”

That same day, Chongo sent the highline on Lost Arrow Spire for the second time (he first sent this line in 1994, author’s note). He wanted to send it in both directions but by the time he decided to do so he was too drunk from the tequila, his choice of liquid courage for the day.

Chongo has always been known for his unique style of slacklining. In Dean’s words, he dances on the line “swaggering forward with an exaggerated sensuality” and with his “hips flowing in a manner not usually seen in men.” Although his walking style has not been adopted by many, his way of standing up on the line is practiced by almost every slackliner in the world today. It’s hard on the knees, but the so-called “Chongo Mount” was created out of necessity when Chongo gained some weight and was unable to stand up from a sitting position (the so-called Sit Mount). According to him, the culprit was the 75% employee discount at the Yosemite cafeteria he received after helping them put the topper on the Christmas tree. Needless to say, he spent so much time in that cafeteria that he could almost be considered an employee. And his presence has certainly increased the cafeteria’s profits because to this day, groups of climbers from all over the world gather at “Chongo’s table” with the hope of meeting Yosemite legends or at least absorbing some of the aura from the past.

MEETING T‑BAG

Towards the end of the month, our friend Jamie came from Northwest Washington to join us in Yosemite. We took him to the Manure Pile Buttress, a rock formation less than 200 meters high that shrinks in the majestic shadow of El Capitan. That’s why it received such an unflattering name, even though it’s a nice rock with some great routes. We wanted to climb some of the classics that climbers preparing for the big walls train on – often free solo. Although we didn’t plan on soloing, we felt a little naked with our somewhat meager gear. Clearly, the hippie-looking man in his forties with long hair, a big straw hat and a joint in his mouth who had been watching us curiously since our arrival didn’t think much of our gear either.

He finally approached us at the base of the Buttress: “What are you going to get into?” – “We were thinking about ‘After Six’ or ‘Nutcracker’, but we don’t know if we have enough cams.” We certainly didn’t. To be comfortable we would want a full rack and a few doubles, considerably more than our six cams and a nut. But climbers online said both climbs could be done with just one set, and we barely used three cams on our route up Half Dome, so… We were determined to continue with our plan, if only to diffuse the expenses of expanding our inventory. The climber raised his eyebrows. “Wow, you’re really going to climb it, aren’t you?” Did I hear a hint of admiration in his voice rather than criticism or derision? Did we impress him with our determination or with our foolishness? Whatever the reason, he instantly started handing us gear. “Here, you’re going to want some #2s, some #3s. And try these Aliens, you’re going to love them, tell me what you think.” We ended up filling our gear loops with far more than we needed, enough cams to place in every crack just because we could.

As we prepared to climb and chatted with our new acquaintance, we found more than a friendly smile hid beneath his sun hat. He introduced himself as T‑Bag, (and later as Mark Garbarini) and told us he belonged to the famous Yosemite climbers who call themselves the Rock Monkeys. As T‑Bag explained, Valley Uprising—the popular documentary about the history of climbing in Yosemite—misrepresented them as the Stone Monkeys, but that’s not the term the members of the unofficial group use. Alena lead the first pitch up ‘After Six’ as T‑Bag began sharing tales about big wall climbing and the times he hung out in Camp 4 with the Stonemasters, including Lynn Hill and Dean Potter. All incredible people, but we especially pricked up our ears the moment we heard the name Chongo Chuck.

“Chongo? You know Chong?” – “Oh sure, he’s one of my closest buddies. We are currently planning a big project together on the Washington Column. We’re aiming for a record because we’ll be climbing with my seven-year-old son. He could be the youngest person to climb a big wall. Another team from Colorado has the same goal, but they also have sponsors and media attention.” I listened to him in dumb amazement, trying not to lose my concentration while I let out rope for Alena. So not only was Chongo alive, but he was about to climb a big wall. And in his 70s! T‑Bag appreciated the numerical symbolism — a budding seven-year-old climber with a seasoned 70-year-old veteran. We confided in T‑Bag that we had only just the other day talked about meeting Chongo. “You know, we could probably make that happen. He’s coming to Yosemite this week and he loves getting to know slackliners. He has a lot of respect for them.” That evening, we set up a slackline on the El Cap meadow with T‑Bag, staying late and swapping stories until darkness and mosquitoes drove us away.

NEW ROUTES IN THE VALLEY

With the return of the cat’s owners we were on our own and the first thing we did was reach back out to T‑Bag. We reunited a few days later, naturally at Chongo’s table in the Yosemite cafeteria. T‑Bag explained to us that he always parks in the same place, the so-called Center of the Universe, a traditional meeting place for Yosemite climbers. The parking lot had seemed pretty ordinary at first glance, but we could suddenly feel the history in the pavement beneath the crowds of tourists. Or maybe we were just imagining it. T‑Bag told us that a Yosemite climber can be recognized anywhere in the world by knowing the Center of the Universe. We felt like we’d gone through some sort of initiation, a rite of passage, because right after that T‑Bag invited us to an area where he’s been developing new single-pitch climbs. “I have a few routes there that need first ascents but I’ve put up enough first ascents in the Valley so I’m saving them to share with the community. Would you be up for that?” It was hard to believe there were still any unclimbed walls in Yosemite, but we’d be fools to turn down a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity like this so we give him our incredulous but resounding “Yes!”

T‑Bag’s son lead us on his bike as we made our way to the new wall. “And what about Chongo?” I asked. “When will he arrive?” – “Chongo will get here this afternoon,” T‑Bag assured us. It was precisely the opportunity I had dreamed of, but my heart started racing as I realized I didn’t have any questions prepared. What do you say when you meet a legend?

About half an hour’s walk from the parking lot we reached our destination. Even at first glance I could see four beautiful lines ready to be climbed. T‑Bag suggested we begin on an easier-looking route with a scrambly start so that his son could climb it later. Alena won rock, paper, scissors and became the first ever climber to lead the route, which she named Ant Queen after the poorly placed nest halfway up and graded it 5.8 (5b fr., editor’s note). Maybe even 5.9 despite the Yosemite’s harsh grading. The other routes T‑Bag and his chosen climbers had already put up along this wall were superhero themed and we were happy to follow the naming convention.

Jamie called his first ascent “The Granite Gambit” 5.10a (6a), and I named my 20-meter finger crack route “Czechmate” 5.10a (6a). We each added a second and third ascent to the new routes before we headed back to the parking lot. 24 hours prior, we would not have guessed there was a lonely boulder left unturned in Yosemite. The idea that we would each get a first ascent was incomprehensible. And yet we had been gifted not only with the ascents but also a day in T‑Bag’s delightful company. We already had more stories from this trip than we deserved, yet I was still in suspense… Had Chongo arrived in the Valley yet?

TAFT POINT HIGHLINE

Dinner with Chongo was postponed. He had decided to stay for a few more days in Santa Cruz because he had recently undergone a gall bladder surgery and his body needed a longer recovery at his age. The doctors discovered that Chongo needed the surgery when he came to the hospital with broken ribs after falling down the stairs. I guess life sneaks up on you like that. Meanwhile, T‑Bag left the Valley for his home in Lake Tahoe, though not before giving us Chongo’s phone number. Chongo seemed eager to come to the Valley to meet us and we were willing to wait a little longer, but our time in Yosemite was running out. We had already planned to be climbing in Red Rock, Nevada by then. However, with temperatures in the desert hoovering in the upper 30s, we were happy for the excuse to stay a little longer in the tolerable weather of Yosemite.

For the next two days we put away our climbing gear and got ready to rig a highline. I decided on the iconic 50-meter long highline at Taft Point (2286 m above sea level), directly opposite El Capitan. Though neither Alena nor Jamie are highliners, they both responded with enthusiasm at my proposal and the prospect of watching the sun rise on the Dawn Wall from the opposite side of the valley.

After a vigorous hike from the valley floor, I managed to rig the highline with Alena and Jamie’s assistance and just before sunset, I was already sitting above the kilometer-deep chasm on the 2.5 cm wide webbing. El Cap looked somewhat smaller from this height. However, for the first time in my life, I felt fear on a highline. I’d been on exposed and arguably scarier highlines before, but I’d never felt anything like this. I couldn’t shake off the idea that if I were to fall I would be falling long enough to realize I was about to die, unless the cardiac arrest got me first. The idea petrified me. I checked the knot on my leash one more time and finally stood up. I was learning how to handle unfamiliar emotions and forced myself to fall a few times. The line was well rigged and I knew I was safe, but I was still unable to fully relax that evening. Nevertheless, I enjoyed the beautiful view from both on and off the line, which together with the sinking sun created a rich yet temporary work of art. That night, while watching the lunar eclipse peak over the treeline, I kept thinking about the highline. Morning couldn’t come fast enough.

As soon as the first rays of the morning sun hit the Dawn Wall I got up on the line. Breakfast would wait. I walked with significantly more ease than the previous day and when I finally sent the line without falling I saw my own relief and joy in Alena and Jamie’s eyes. I might have cursed at them but I’m no Darrin Carter, so instead it was their yells and cheers that helped me across. After we derigged and packed up, Jamie sent a message to Chongo with a new photo of me doing the Chongo Mount before El Cap. The cell service, whose absence we had become accustomed to down in the valley, was marginally better up here as we received an immediate phone call from Chongo. “Wait, who’s talking?” – “You talk, you’re the highliner!” – “No, that’s awkward, we should all–” but then there he was. His voice speaking to us like a long-rumored cryptid popping up in broad daylight. He was real, and very much alive. And somehow, talking to him felt like chatting with an old friend. Despite the weak reception, we caught the essentials – Chongo was finally about to leave Santa Cruz and would arrive in Yosemite at dawn the next day.

“I HAVEN’T DEPARTED YET”

When we woke we eagerly looked for word from Chongo and unable to wait any longer, we texted him over breakfast. To our disappointment, but no longer surprise, he told us, “I haven’t departed yet.” He got tired while packing, and the prospect of a four-hour drive across the state discouraged him. But he would definitely come tomorrow morning and meet us at noon. It was a bit like waiting for Gandalf, but the wizard really appeared at dawn as promised. Unfortunately, in Chongo’s case, it was more like waiting for Godot. Even though we postponed our departure for one more day, we had already come to terms with the fact that this dream, this whimsical, fantastical dream of meeting Chongo in person was after all too good to be true.

The heat and crowds from the official start of the tourism season was starting to get to us and we were itching to head up north to Smith Rock. Our original plans to go sport climbing higher up in the Valley were doubly thwarted by Chongo’s latest delay and the still snowed-in road to Tuolumne Meadows. And the strenuous hike to Taft Point had left us tired and a bit listless. At loose ends, we went to Curry Village to inflate the car tires and reassess our options. Suddenly, Chongo called us again: “Look, why don’t you come to Santa Cruz? I’m crashing at my friend’s summer house, he’s a world-renowned physics professor at Stanford. It’s nice here and I’m right by the beach. You can stay as long as you want.” We looked at one another. Why the hell not? We needed a rest day anyway, and Santa Cruz wasn’t even that far, not by American standards. We had a final picnic in the El Cap meadow, our favourite spot, and said goodbye to the Valley. I was sad, but I already knew that I wanted to come back. The big walls had left me with big dreams to scale.

“Look, why don’t you come to Santa Cruz… It’s nice here and I’m right by the beach. You can stay as long as you want.”

On the way to Santa Cruz, we made a quick stop in Merced to get a new tire. It was unbearably hot there and we much appreciated the cool breeze and mild coastal climate as we arrived in Santa Cruz. We enjoyed sunset dinner on the beach, just a few minutes from where Chongo said he was staying. In the parking lot, we had to deal with one last obstacle on the way to this hard-won meeting when a small body part fell off from our Prius. Fortunately, we got help in the form of some old wires and miscellaneous tools from a stoned elderly hippie who parked right next to us in an old Volkswagen, in which he seemingly transported everything that had ever come his way. Including a stoned hippie lady who we almost didn’t notice amongst all the junk.

A cool breeze and mild coastal climate ushered in this new and entirely unanticipated stage of our journey. Chongo welcomed us in a cheerful mood with a cheeky smile on his lips. On the way to the apartment he observed us but didn’t make any effort at small talk. “So, which one of you is a slackliner?” he asked as soon as we sat down. On the floor, of course, though the living room was full of couches and armchairs. Chongo told us he didn’t even use the apartment’s comfortable king-size bed. “I don’t know how to sleep anywhere but on the floor.” Chongo soon warmed to our conversation and after a few hours he would barely let us speak. It didn’t matter; we came to listen to him.

PARTY ON THE FLOOR

More than anything else we discussed politics and physics as Chongo’s views on climbing have changed considerably over the course of his life. After he turned fifty, he gradually moved away from climbing and reflected on the meaning and usefulness of this lifestyle: “I provided a great deal of inspiration to a lot of people to pursue a narcissistic activity, and I wonder if I’ve done good,” though he also told us that climbing can be a positive contribution as long as the climber brings back to society the values that their lifestyle espouses.

“I provided a great deal of inspiration to a lot of people to pursue a narcissistic activity, and I wonder if I’ve done good.”

We conversed in Spanish for a while and Chongo told us stories from his life in Mexico. I have lived there too, but my time there was nowhere near as adventurous as Chongo’s. In between musings on electoral politics and breaking down general relativity into layman’s terms, we also managed to turn the conversation to climbing and slacklining several times, listening in alternating humor and rapture at Chongo’s tales about his life in the Valley. We learned that not all climbers belonged to Team Chongo. He got particularly angry when he recalled a sexual assault, allegedly committed by one of the local climbers. This horrific incident damaged his affection for the climbing community and he stopped generalizing climbers as a homogenous group.

When it comes to slackliners, however, Chongo continues to insist: “There is not a single evil highliner in the world.” He said that it does not go hand in hand with what a highliner must have inside to succeed at great heights. Chongo reminisced about going with other slackline pioneers to the Lost Arrow Spire, where they were attempting the first ever highline sends. Although he’s climbed big walls, Chongo has always felt fear on a highline so he prefers to slackline close to the ground. He became a master at surfing and bouncing. That’s why he looks up to highliners who are able to control their fear and is proud, justifiably, that he motivated many of them to their best performances. Chongo asks me to send him the pictures of me highlining at Taft Point and Alena whispers in my ear, “He thinks you’re a bitchin’.” I think more so that it’s impossible not to imbue some of the magic and history in a place so well loved.

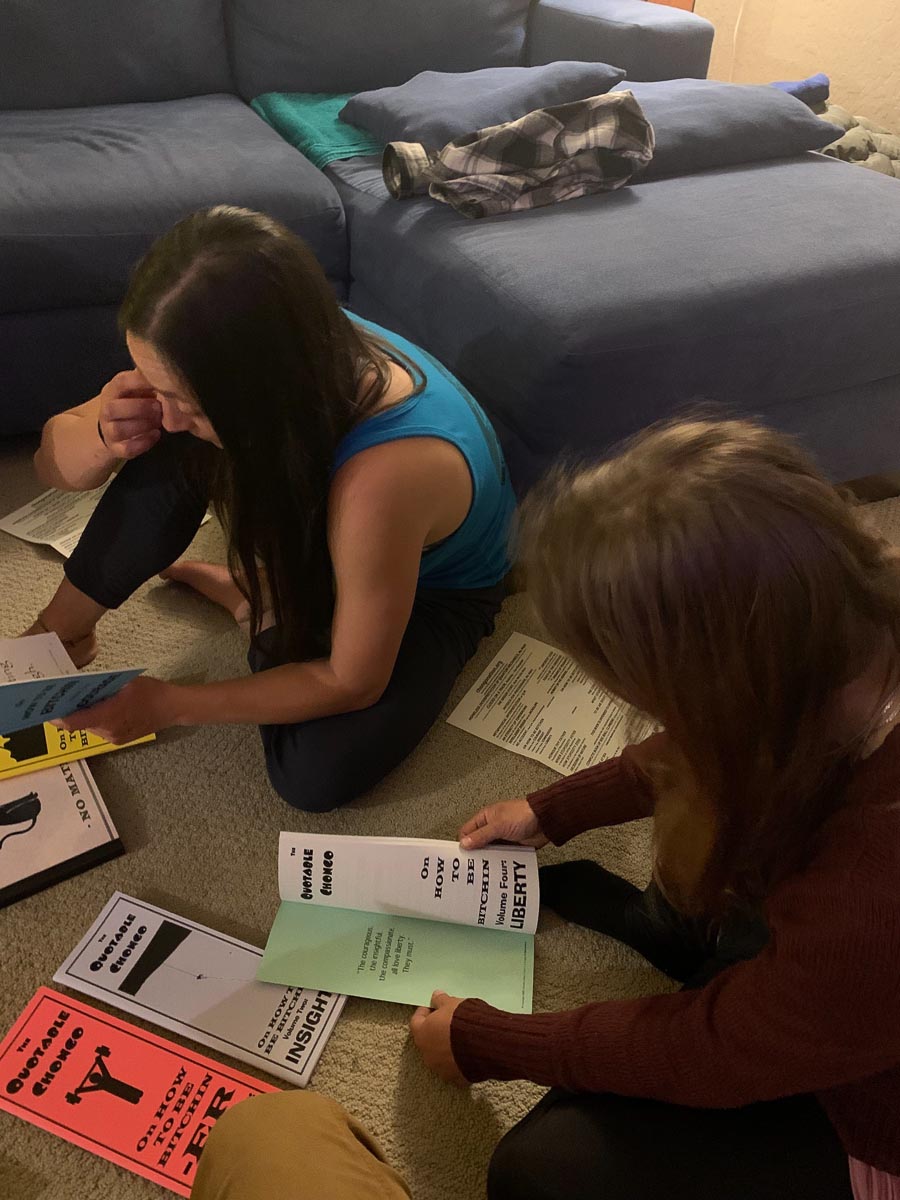

FEED THE WRITER

During the evening we had the opportunity to check out most of Chongo’s books. He self-publishes and sells them either online through his “Chongo Nation” website or in person when he visits his favorite climbing areas. But he has also worked with editors who offered him their services for free. I’m especially captivated by the thick book with nearly six hundred pages full of technical advice for climbing big walls. Chongo looked at me slyly and said, “You know, anyone who climbs has it in them to climb El Capitan. The only thing stopping them from succeeding is that they don’t know how to properly manage the equipment on a big wall”. He then handed me another extensive manual with detailed drawings of proper belaying techniques. I didn’t have room in my pack for the belay book or the “bigwall bible” (as it is colloquially known), but I picked out a smaller guide titled Love and Hate at Sea: A Book About Wall Partners, which also includes an old photo of T‑Bag. It’s a nice souvenir. As Chongo kept encouraging me to climb big walls, the seed that T‑Bag already planted in Yosemite began to sprout inside me.

Chongo became particularly animated when he talked about physics. He is currently working on a book on relativity and we rounded the long evening off by watching a physics lecture given by our absent host, the distinguished Stanford physicist. We then went to sleep on the unused bed while Chongo lay down on the floor as usual. He was the first one awake in the morning and we caught him writing – with a joint in his mouth, of course. I was beginning to understand how he managed to produce such a high number of books – this guy has exemplary self-discipline and work ethic. Or rather, he enjoys writing so much that he never considers it a job, sometimes going at it for 10 hours a day.

Still, he interrupted his flow to ask us about some things that came to his mind over night. He wondered, for example, if Alena learned Czech when she lived in Prague, or if Danny Menšík still highlines. At least I think he was asking about Danny; he didn’t remember his name but accurately described the bitchin’ Czech highliner that he once met in Yosemite.

T‑Bag texted us just before we left: “Give Chongo something healthy to eat.” He graciously declined oatmeal for breakfast, so we at least left him a box full of cherries in the kitchen. I doubt he ate them. It’s almost as though he doesn’t even need to eat because what nourishes him most is his unending enthusiasm for living and his fascination with the world that surrounds him. Chongo does not fit the mold of a spiritual person in the modern sense of the word. He can get really angry about the current political system, racists, chauvinists, Republicans, Christians, and human stupidity in general. His lifestyle is primarily a protest against a system that privileges certain groups of people and discriminates against others. But though there is a certain bitterness in him, he appreciates all the little things in life. Many others before me have discovered how much there is to learn from one who has experienced as wide a slice of life as Chongo. and I very much doubt I will be the last.

Before I met him, I knew Chongo Chuck as the godfather of slacklining and the king of all dirtbags. Now I know he is above all an intellectual. An intellectual dirtbag who found a way to live his life to the fullest despite all the obstacles in his way. How did he do it? He’s just bitchin’.

EXTERNAL SOURCES

Brick, Michael. „For Rock-Climbing Guru, the Sky Is His Roof.“ The NYT, 2008.

Mortimer, Peter, Rosen, Nick, and Lowell, Josh. Valley Uprising (2014).

Ogilvy. „Create or Else: Chongo“. Youtube, 2010.

Potter, Dean. „The Space Between.“ The Alpinist, 8 Nov. 2013.

Chongovy osobní stránky Chongo Nation.

__________