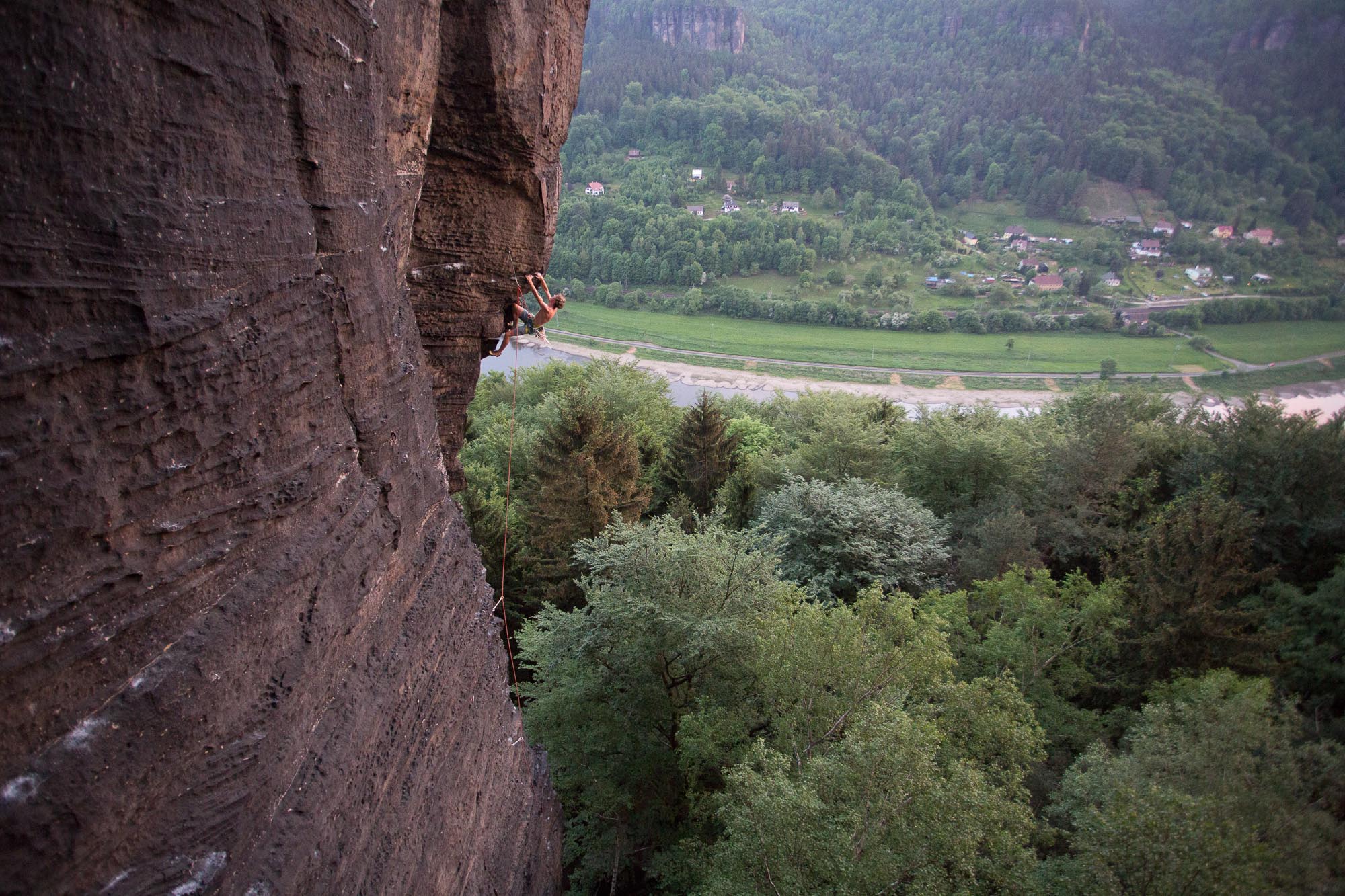

ELBE VALLEY VS. ELBSANDSTEIN

Elbe Valley and Elbsandstein. These two world-class sandstone climbing areas are located in close vicinity, yet, people usually talk about each of them separately. It almost feels like if these areas had nothing in common and were located in different galaxies…

HISTORY VS. PRESENT

If you want an example of a place with a truly epic history of climbing, it’s Saxony. Schuster, Strubich, Arnold and Güllich – these are just some of the characters who climbed and made first ascents there. Arnold, for instance, is responsible for over 3000 lines in the area. Saxony’s history is one of legendary figures – from those who surmounted the first spires in the beginning od 20th century, like Oliver Perry-Smith, who drove around in his American car and threw huge parties celebrating each of his epochal first ascents, to the young Karlheinz Gonda, who went headfirst into the most extreme lines of his times.

But the Elbe Valley (called „Labák“ by locals) in the Czech Republic has its heroes as well – for instance the Weingartl brothers, who climbed in the valley in the 70s and 80s and made some epic routes – just try and climb some of their scary gems on either Right or Left Bank and you’ll understand. The golden age of the local climbing took place in different times, though – the Elbe Valley had its first ascent boom in the 1990s while the Elbsandstein/Saxony lured climbers already a hundred years before that. (See our article about the breakthrough lines). Looking at these numbers alone, it’s clear the Saxon history of climbing is more interesting. A point for Elbsandstein.

PROTECTION VS. FEAR

„Elbe Valley is all about sport routes while Elbsandstein is about classic lines…” at least that’s what they say. But is this true? Not really… just try “Motolice” VIIc (5c+ fr., though in reality, it feels harder) on the right bank of Elbe – a 60-meter VIIc with two ringbolts, or on the other hand a 15-ringbolt “Fesche Müllerin” graded Xa (7b+ fr.) and you’ll see that the statement doesn’t hold true.

Sure, Saxony offers many classic lines protected by slings and knots – statistically, the old sandstone lines prevail but don’t forget that in both of these areas, climbers have been always making their first ascents ground up – so if there was no place for a sling, one had to place ringbolt. And to be honest, those X‑graded routes often don’t offer too many options for solid slings. So… Even the Elbe Valley has its own classic lines and Saxony its „sport routes“. For local climbers in both areas, all it takes is keeping your eyes open and gathering some courage to step out of your comfort zone. A point for both contestants.

RINGBOLT VS. BOLT

Is a ring better than a bolt? An interesting question, indeed. The justification for ringbolts can be found in their history and development of climbing in general. In Saxony, people climbed local rocks even before the invention of the carabiner that was later conveniently used to connect a rope to an anchor. Before the advent of carabiners, climbers had to untie at the anchor, thread the rope through the ring and tie in again. During “clipping in”, one usually held the ring with his or her elbow with their arm threaded through. That’s why the oldest rings tend to be so big.

The rings survived the invention of the carabiner (godspeed!) and later the chest- and sit-harnesses because they were usually used not only as a protection point for clipping in but as an belay anchor as well. People used rings as anchors and climbed even the first IXb (french 7a+ approx.) routes with them, up until the early 70s. Kurt Albert, the inventor of the red point, after which the sport climbing boom came, was still a toddler.

The regular bolt is brought about only later by sport climbers – its size shrank because it was no longer used as an anchor but only as a protection into which you could easily clip in quickdraws without the need for untying. The bolt is smaller and lighter but you certainly don’t want to find yourself in a situation when you need to belay your two friends from it. The ring can come in handy in dire situations as well – imagine trying to grab a bolt while you’re losing balance over sketchy grounder. So what’s better… a sporty bolt or a classic ringbolt? It depends on the route and the perspective. A point for both contestants.

CHALK VS. SWEAT

It’s well known that the use of chalk is strictly prohibited in Saxony and people actually do obey the rule. In the Elbe Valley, you can use chalk officially but just in certain areas. What is better? Well, that’s not an easy question. Anyways, an over-chalked route is not a nice sight but nor is a clean line with greased-up holds.

Try to adjust your style of climbing and to not ruin the rock for the others… if you’re climbing without chalk, try not to sweat too much. And if you use chalk, always brush the holds after yourself. That’s what the brush loop on your chalk-bag is for. Comparing the two ethoses, though, it’s clear that in Elbe Valley, you have the freedom to choose classic lines or the chalked-modern ones.. A point for Elbe Valley.

TICKMARKS

While in the Elbe Valley, holds are usually marked with chalk, in Saxony, a more brutal method is employed: nails. Yuck! Fortunately, the Saxon committee for climbing recently decided that climbers can use a piece of wood to mark their holds. Yet, they haven’t specified what kind of wood it should be. Oak, beech or a Douglas fir? We are quite curious as to how manufacturers of climbing gear will respond. “Hey mate, you’ve seen that new BD twig? Does it mark well?” A point for Elbe Valley.

(The SBB union issued a text, in which they allow only “removeable marks” such as a tape or soft wood, editor’s notice.)

LABE VS. ELBE

Both Elbe Valley climbing area and Saxony are located by the Elbe river. Interestingly, the Czech Elbe area is situated on a ‘lower floor’. What does that mean exactly? That remains a question to be answered. Does it signify that modern sandstone climbing is going underground? Anyways, it only takes to inflate your packraft or mattress and you can easily get from the Czech Labe area to the German Saxony. A point for Saxony.

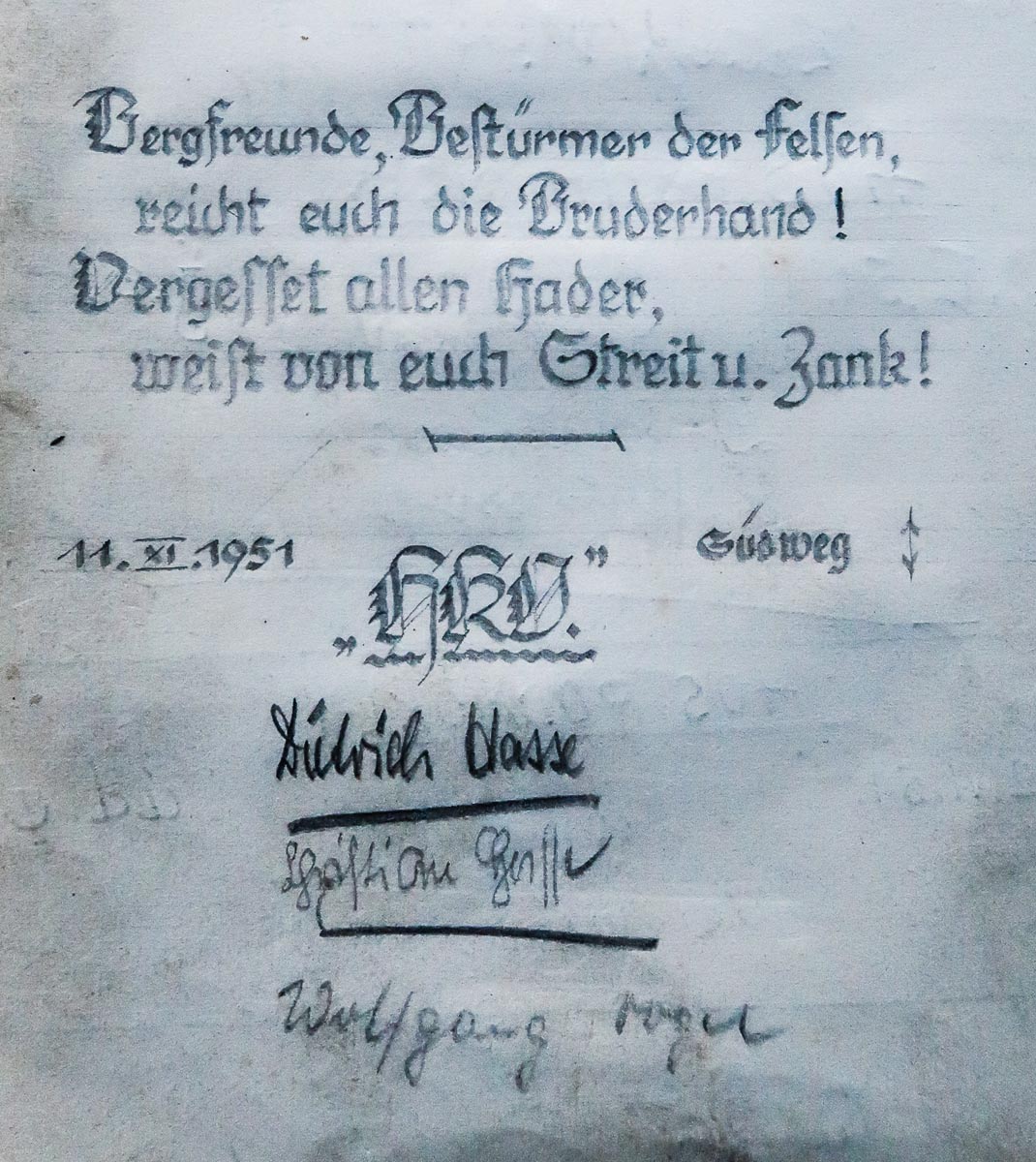

LOGBOOKS

Logbooks on the tops of the sandstone spires are an essential part of sandstone climbing culture. The discipline of log authors in each respective area, however, sharply differs. Saxons usually write clean and well structured entries following clear rules and using their full names, while the Czech entries are often quirky, creative and signed with various nicknames oftentimes involving a raw, unfiltered stream of consciousness or personal psychoanalytic confessions. Not judging the content, there are more logbooks in Elbsandstein than on the Czech side of the Elbe Valley. A point for Elbsandstein.

TOWERS VS. WALLS

The Elbe Valley hosts about 314 towers while Saxony has approximately 1100. The Valley, however, offers 354 rock cliffs (walls) and Saxony only three. What to make out of that? Perhaps that Saxony has no cliffs? No at chance – they’re there! But climbing is prohibited on them. Some say that the national park guards were quicker than the climbers and banned it before they got the idea that massifs can be climbed as well. Others go even further to claim that Saxons never got around to that idea at all. There’s no logic in climbing anything that is not a tower, right? Climbing to a simple belay point instead of bis zum Gipfel? Was ist das? Wo ist ein Gipfelbuch? Und wo ist ein Aussicht? Anyway, let’s get back to the hard data. In Elbe Valley, you can climb both. A point for Elbe Valley.

(The open Saxon cliffs include Lilienstein – Westecke and Königstein with the oldest sandstone route ever made: “Abratzky-Kamin” IV (4a fr.) from 1848. The fourth is an asterisk labeled grade four “Südwand” at Grosser Zschirnstein from 1903)

ROUTE QUALITY

Routes? They beautiful on both sides of the border. A point for both contestants.

BERG HEIL VS. HORE ZDAR

The tradition of berg heil (a special logbook entry reserved for the first climber to climb the tower in the current year) is well established on both sides of the border and works almost the same. On the Elbsandstein, however, climbers usually add a citation or some clever, thoughtful line. How didactic! It is evident that the Germans follow the tradition of their big thinkers even while performing such a “non-philosophical” activity as climbing is – let’s not forget that it is the country of Kant, Hegel and Schopenhauer.

We don’t mean to say that climbers are uneducated dimwits, but anything that boosts the intellectual-emotional development of the community definitely counts. Imagine if we mixed some deeper thoughts such as the butterfly effect or Schrödinger’s cat into the usual pub chat about crimping or not crimping the hold under the third bolt. A point for Elbsandstein.

PUBS

In Elbsandstein, you cannot find the U Kosti pub. Plus you pay in Euros and drink strange beer. A point for Elbe Valley.

LANDSCAPE

The Elbe Valley and Elbsandstein are located right next to each other but we must admit that the Saxon sandstones have a bit more varied surroundings. On the Czech side, you have the tall cliff faces on the sides of a canyon of the meandering Elbe valley and on the German side, you can find for instance the “multi-storey” Schrammsteine massif with views of the monumental Falkenstein. And we haven’t even begun to mention the hikes and boattrips in Rathen and the tram through the deep Kirnitztal. The Czech Elbe Valley might be beautiful but Elbsandstein gets the point here.

HARD LINES

Looking at the concentration of hard (and most importantly, beautiful!) lines, the Left side of the Valley really is quite unique. In Saxony, you could find plenty of routes graded X and XI (7b+ to 8a) but these lines get climbed only occasionally, whereas in Elbe Valley, these are the most popular. Sure, you can get a number twelve in Labák as well as in Elbsandstein but comparing XIIb (9a fr.) lines such as “No Cheating Stone Please” on Falkenstein by Thomas Willenberg and “To Tu Ještě Nebylo” on Malý Ďábel made together by Ondra Beneš and Adam Ondra, the winner is clear – when it comes to the hard lines, Elbe Valley gets the point.

FINAL ROUND

It might seems so but the goal of this article is definitely not to build walls between climbers and areas. In fact, it strives to do the exact opposite! Saxony and the Elbe Valley are close neighbours. Each has its pros and cons, which is well illustrated by the final score we have reached in this contest. 8: 8

When Alex Honnold visited Labák he could not understand that the Elbe Valley and Elbsandstein are not considered a single area. He was so confused that he climbed grades Xb (7c+) chalkless where he could use the chalk and almost asked for draught Pilsner in a Saxon Schmilka kiosk.

Oftentimes, climbers tend to look for differences where there are more similarities but our communities stay strongly connected nevertheless through the rocks, nature, passion for movement, freedom, fun with friends, overcoming limits and fears. But mostly: climbing itself and spending time on our wonderful sandstone rocks.

__________