CLIMBER TURNED SEA DOG

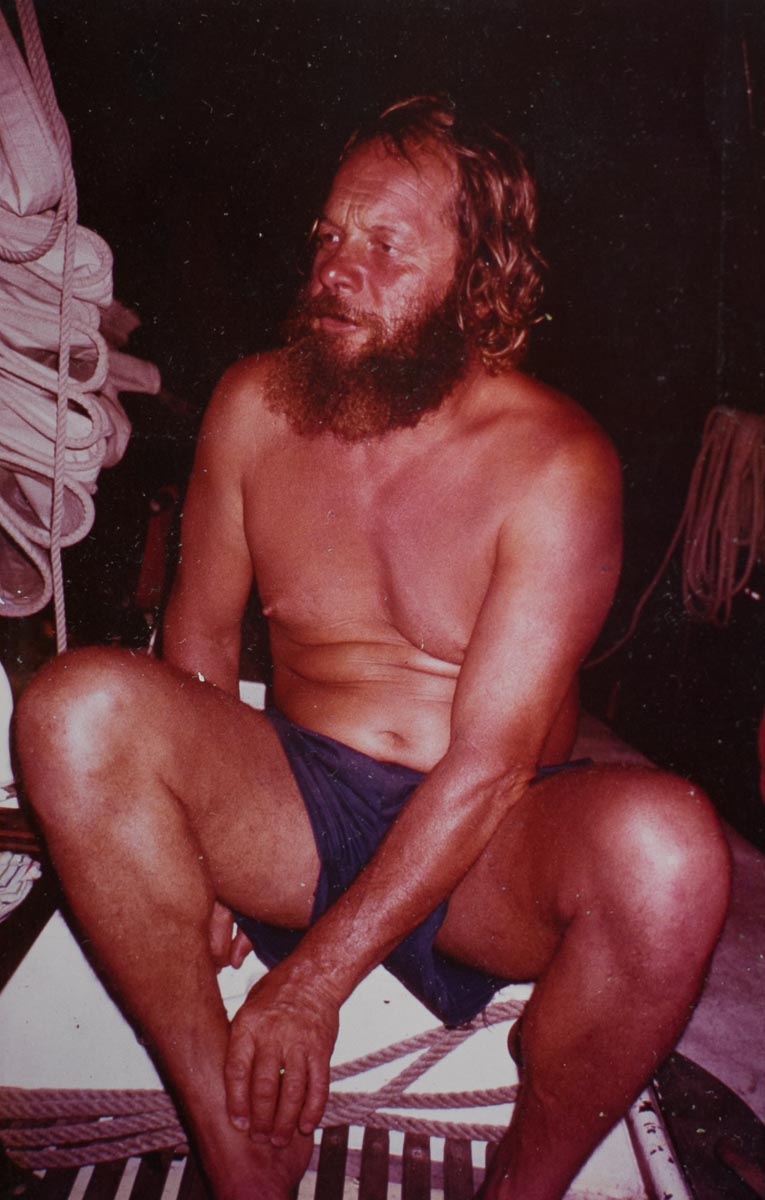

“Diving with a bottle seems pointless to me. That thing on your back deprives you of any real experience. That’s like hanging onto ringbolts while climbing!” Karel “Kokša” Hauschke – sandstone climber and a captain!

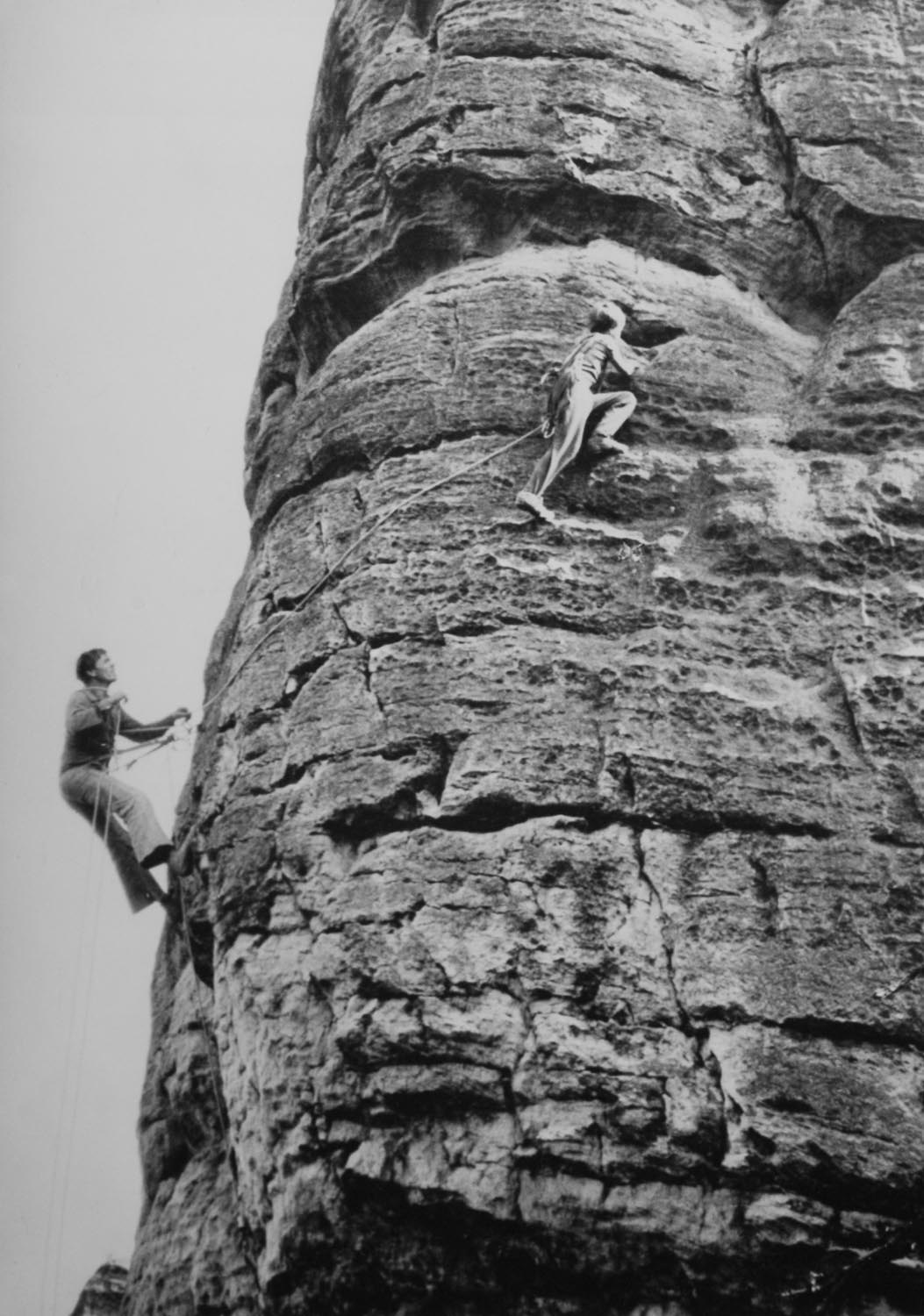

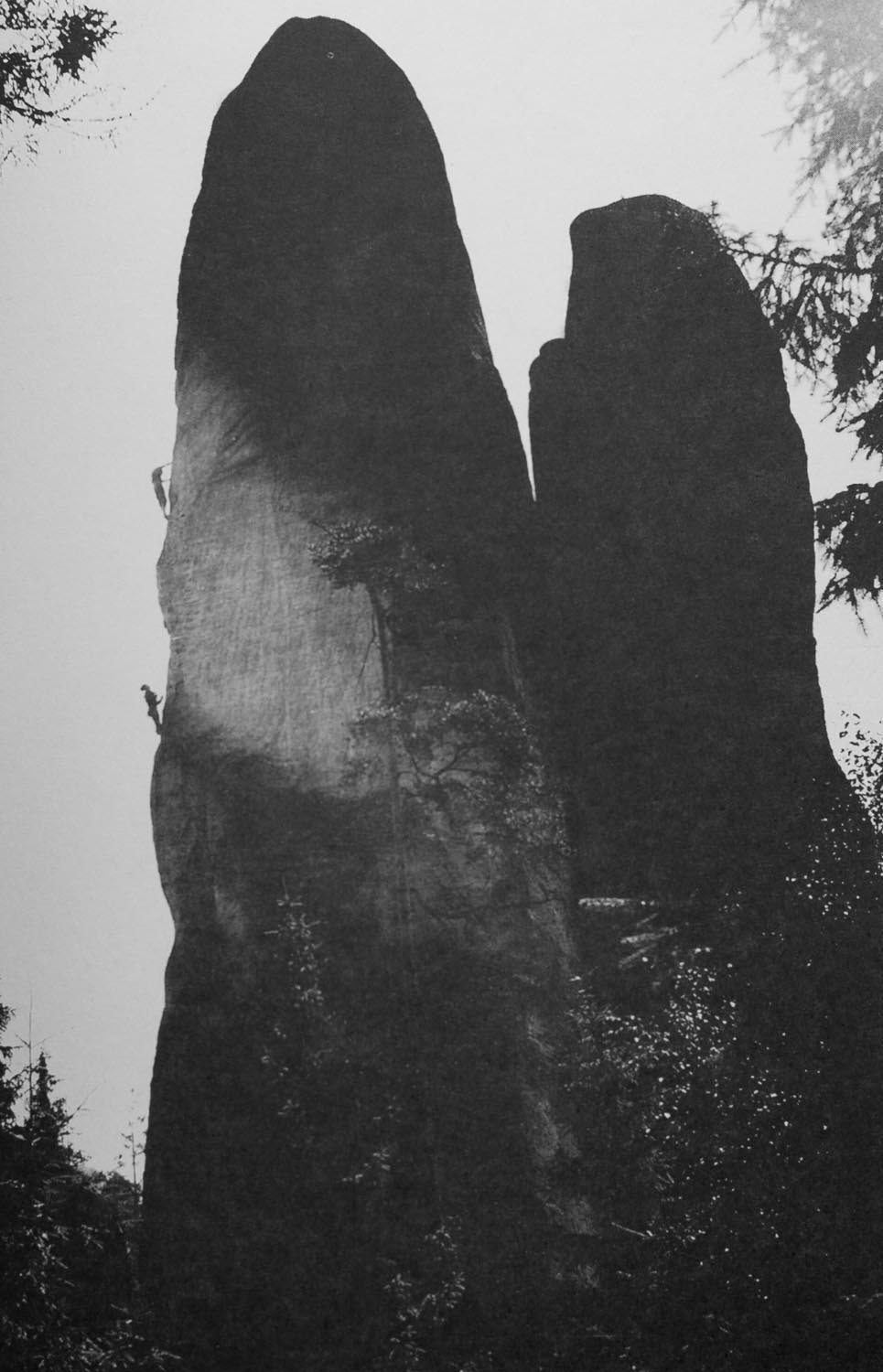

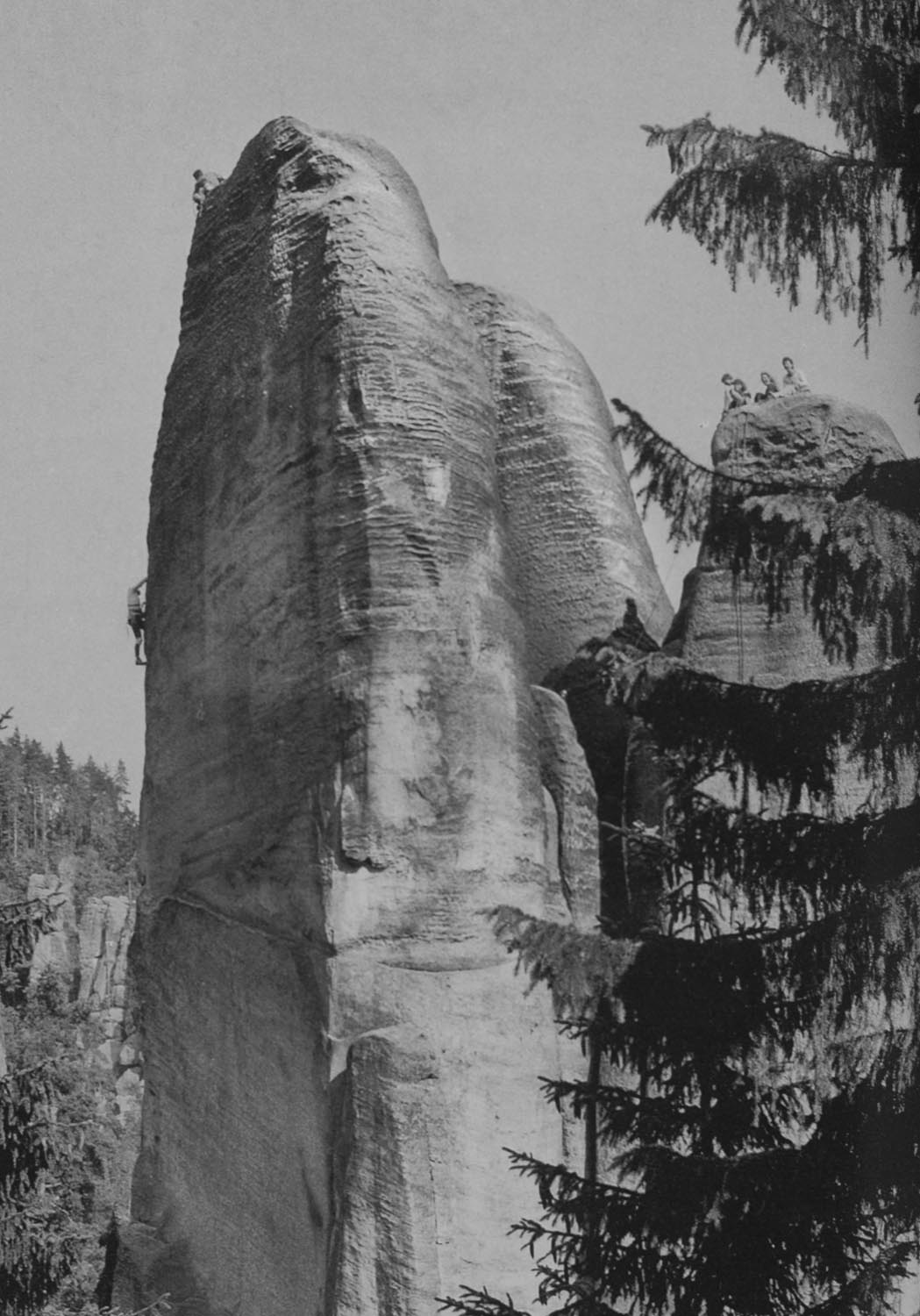

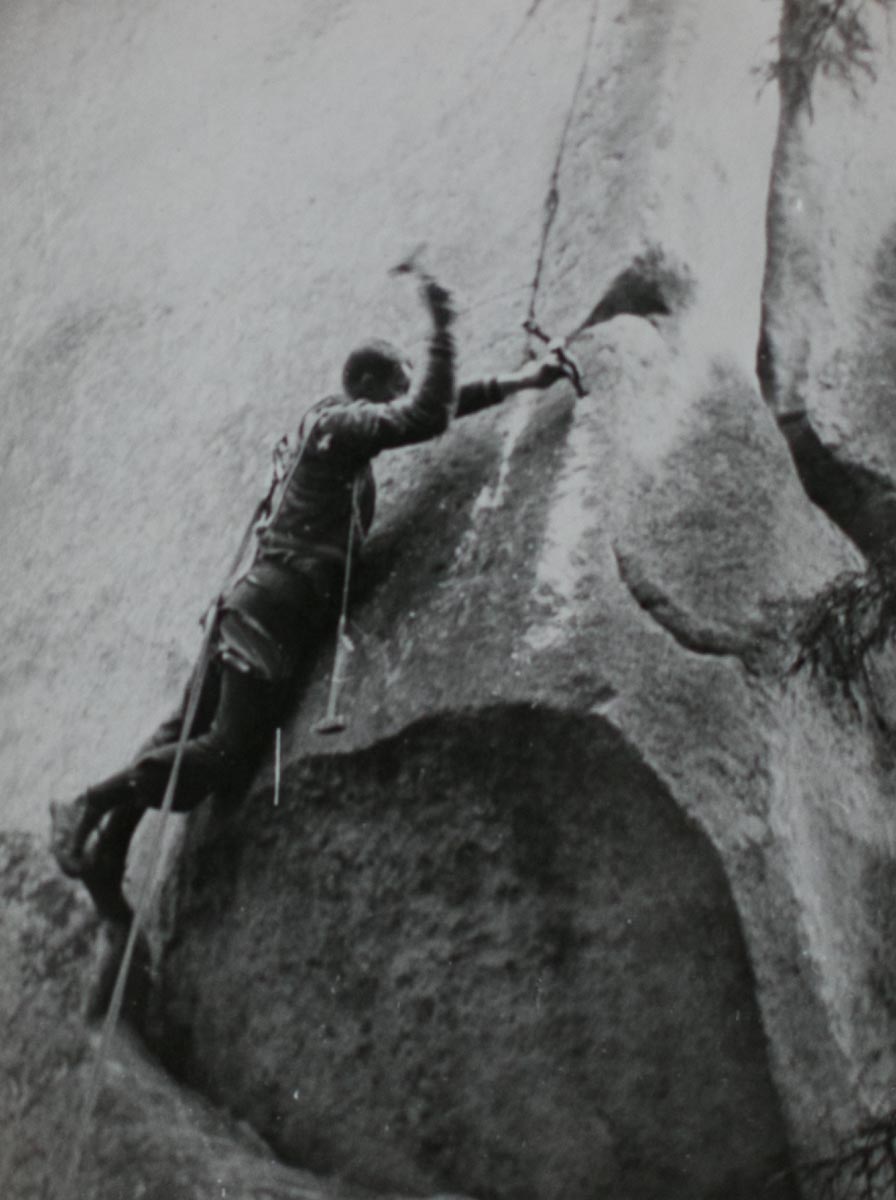

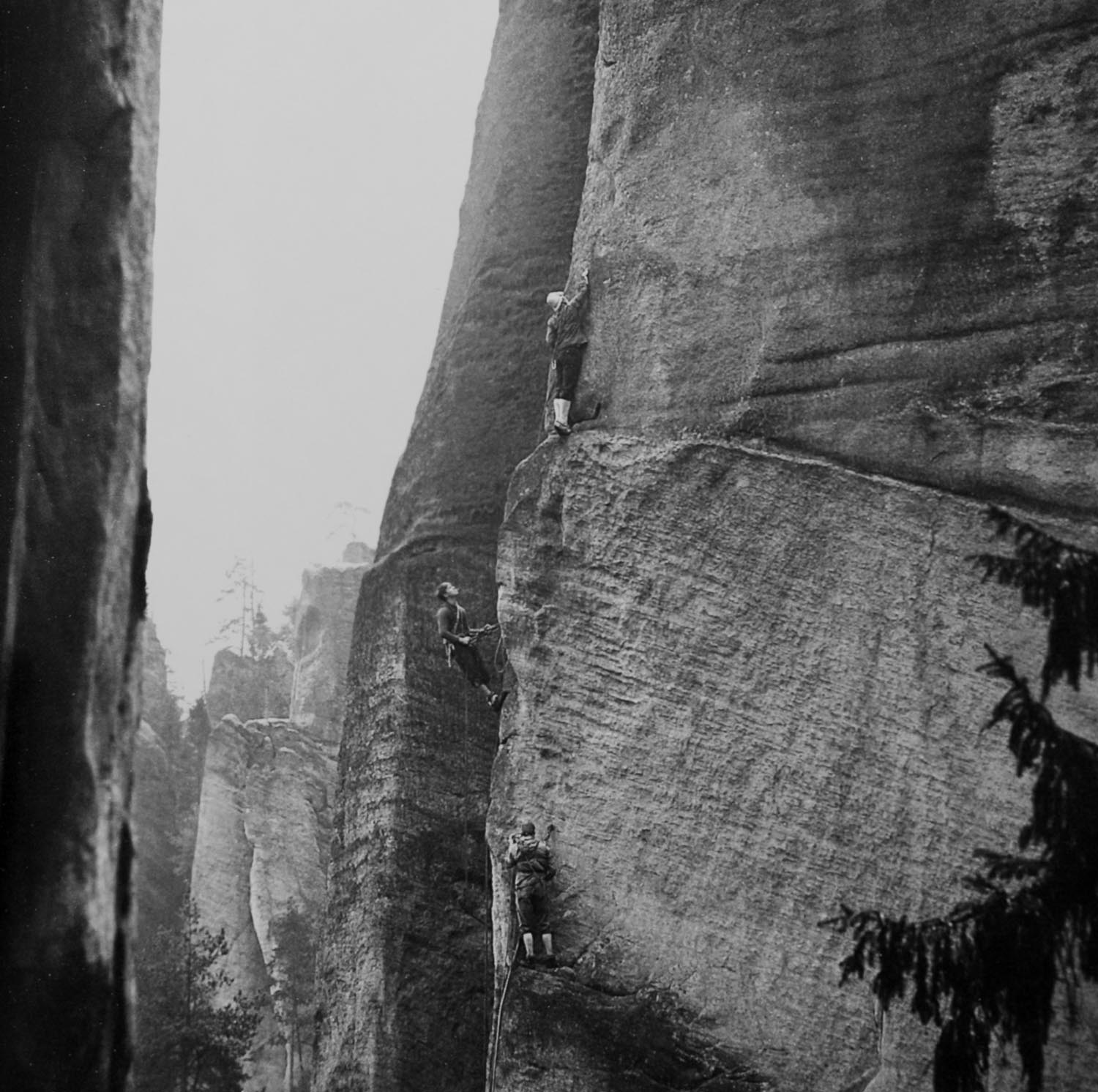

Sensation shakes with the whole Adršpach! Herbert Richter from GDR just finished a first ascent of “Severovýchodní stěna” (VIIIa, cca 6c fr.) at Jitřenka tower. “Richter is well ahead of his time! In the next 15 years, nobody would climb it,” swears Karel Šmíd, who made the first guidebook for climbing in the wider Adršpach area.

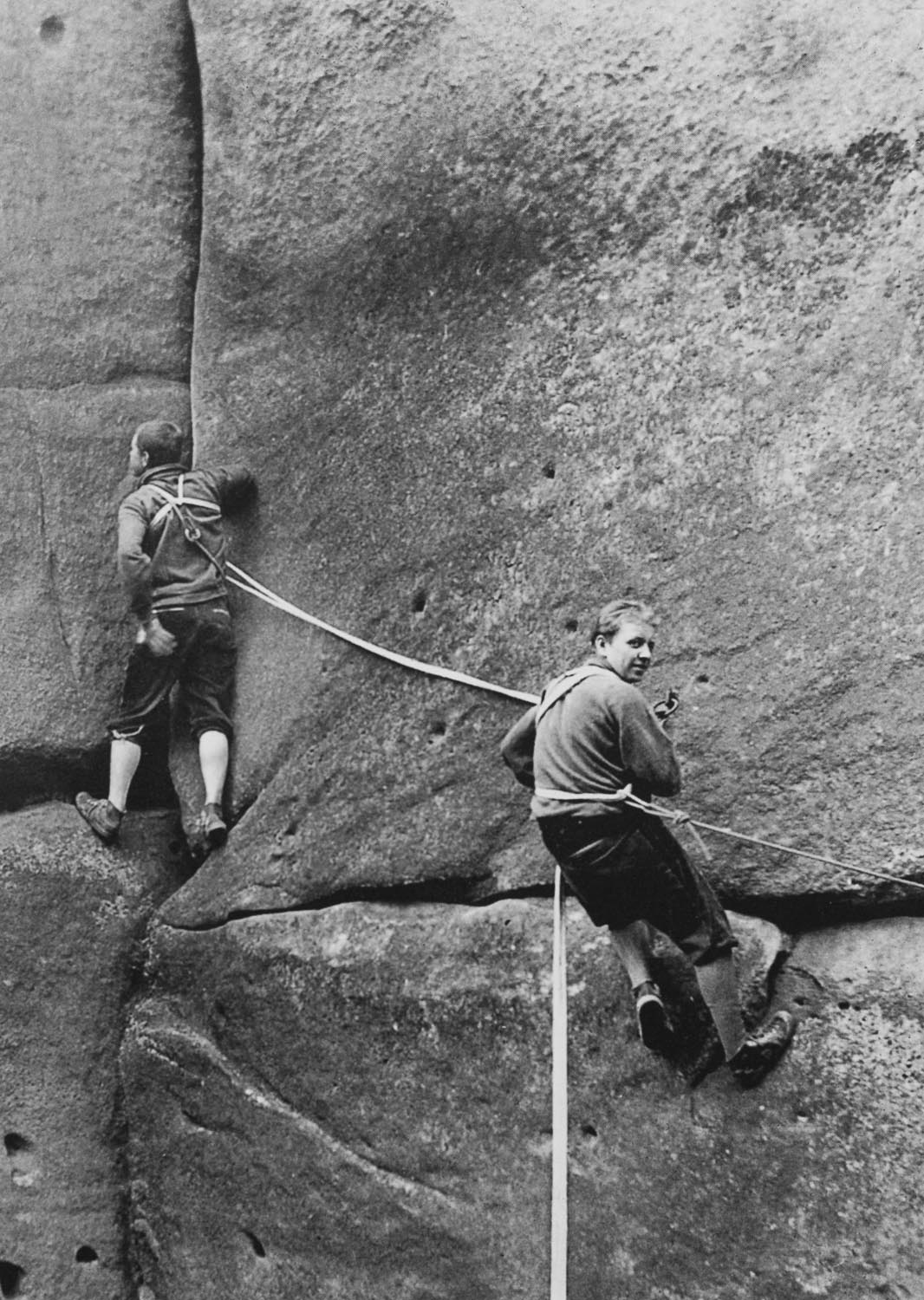

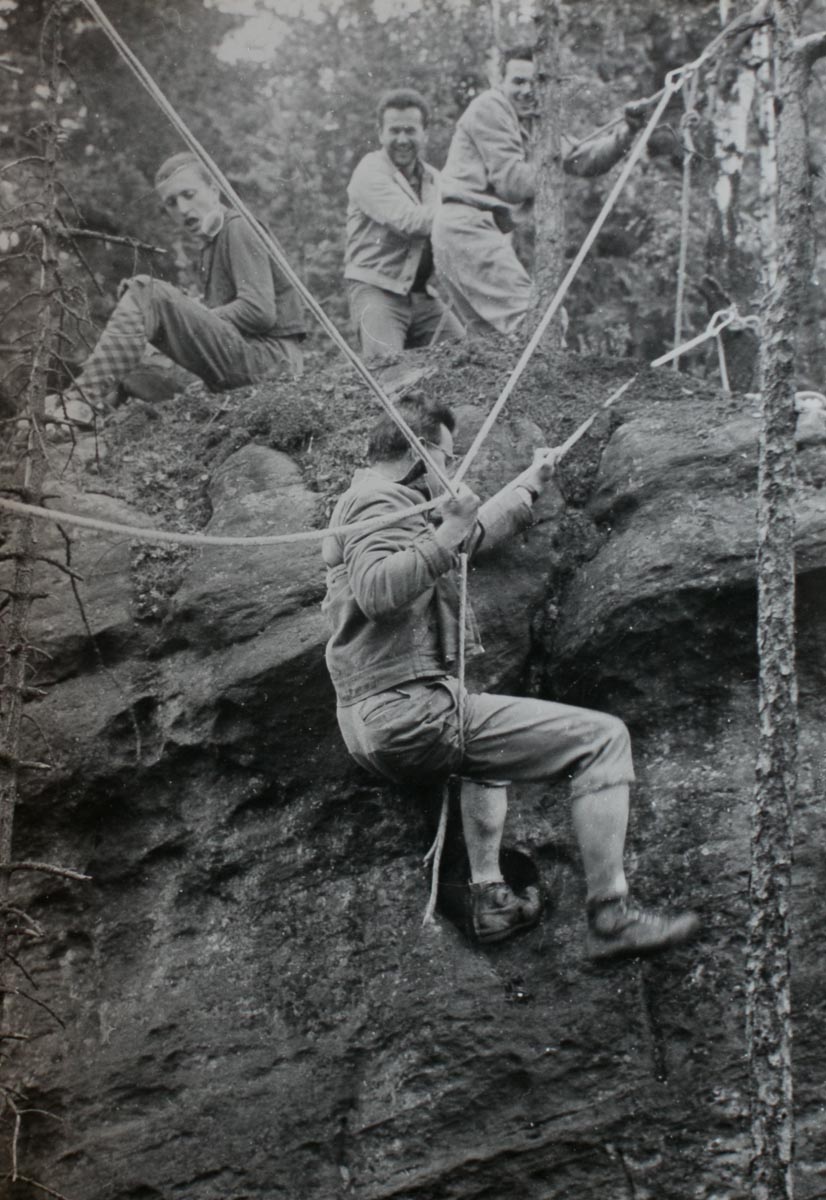

“A few days later, I was strolling through the rocks, and there was Kokša (read as it was written “Koksha”, ed. notice.) hanging at the first ringbolt – all alone. He shouts at me: ‘Come and join me! Nobody wants to climb it.’ There was a loose end of the rope hanging to the ground so I couldn’t resist the temptation and tied in. After all, we managed to climb the wall of Jitřenka,” recalls one of his climbing partners, Jenny Farkaš from Náchod.

“Well, Kokša did it – he led the way and got me to the top. His climbing skills were far superior than those of the rest of us. Most of his friends could only belay him on his projects,” says Jenny. After Kokša fell in love with climbing, he barely left the rocks. He took climbing as seriously as he had judo before. It is said that he was even buying his fellow tinsmiths bottles of rum to take shifts instead of him so that he could devote as much time as possible to climbing the virgin walls and cracks of Adršpach.

Those who know Kokša just from the guidebook entries could be surprised that he managed to do all those legendary ascents in the course of mere six years. His climbing career was short, albeit unforgettable. “Two hobos who do only seven grades,” was what others called the duo of Kokša and Jarda Krecbach. They got famous for the hardest lines including the bold and difficult “Houbařská Stezka” (VIIIb, cca 7b fr in real.). You can find this route at one of the majestic towers along the main tourist trail. Seldom somebody manages to open the logbook on its summit.

SIX YEARS, SIX LIVES

Kokša, however, was longing for other adventures as well… And thus, in 1965, he bid farewell to his friends at the former Náchodská hut and delved into a wholly different world.

First, he managed to climb one of the hardest lines in the mountains and then, as he says, he “lost it to the sea”. He built a 15-meter sailboat – “the snail shell”, in which he circumnavigated the globe several times. After some years, he became a ship architect and a captain with 40 years spent on deck. In French Guiana, he helped with the building of a launching pad for a space shuttle; in Polynesia, he helped his friend with the woodwork on a house with a bamboo roof; he discovered his talent for painting; learned four languages; could freedive into the depth of 30 meters and fish for his family…

Despite all his skills, he held trad climbers and old sailors in high esteem. He led a humble path toward the same level of mastery.

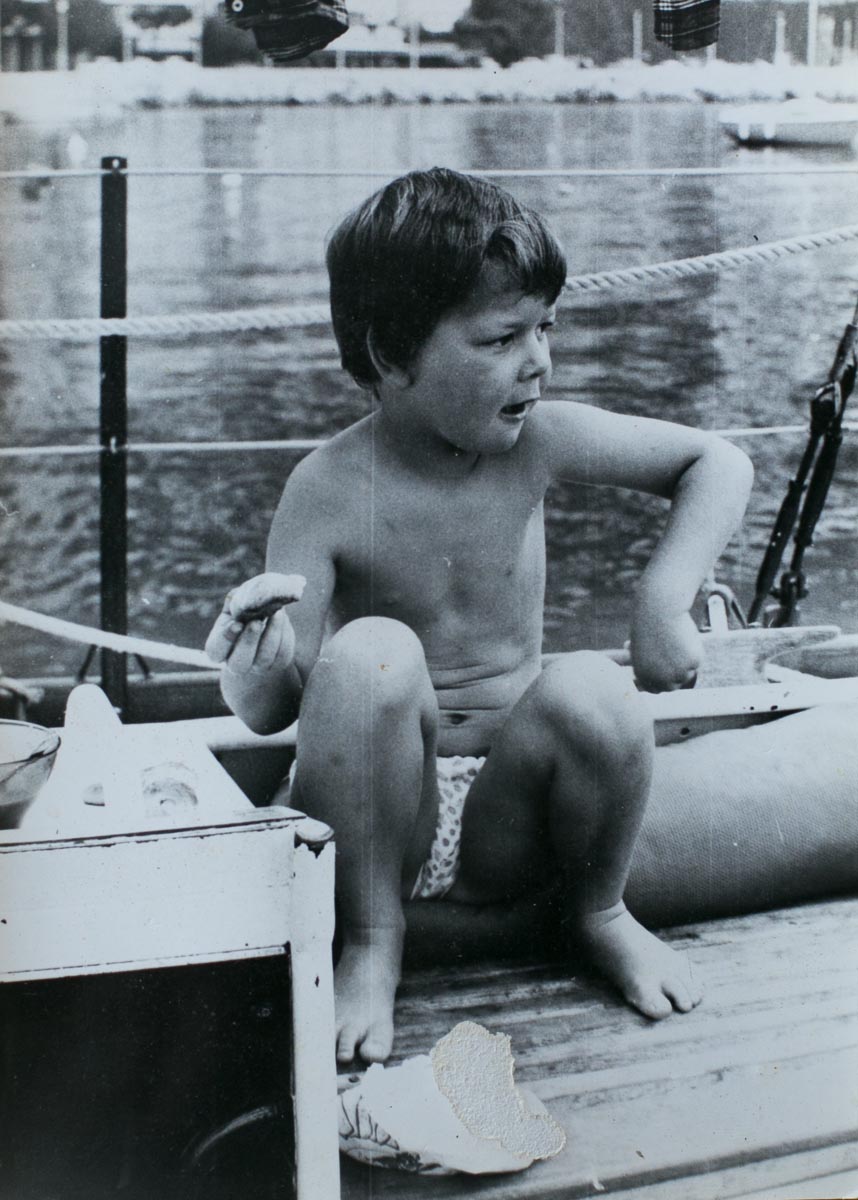

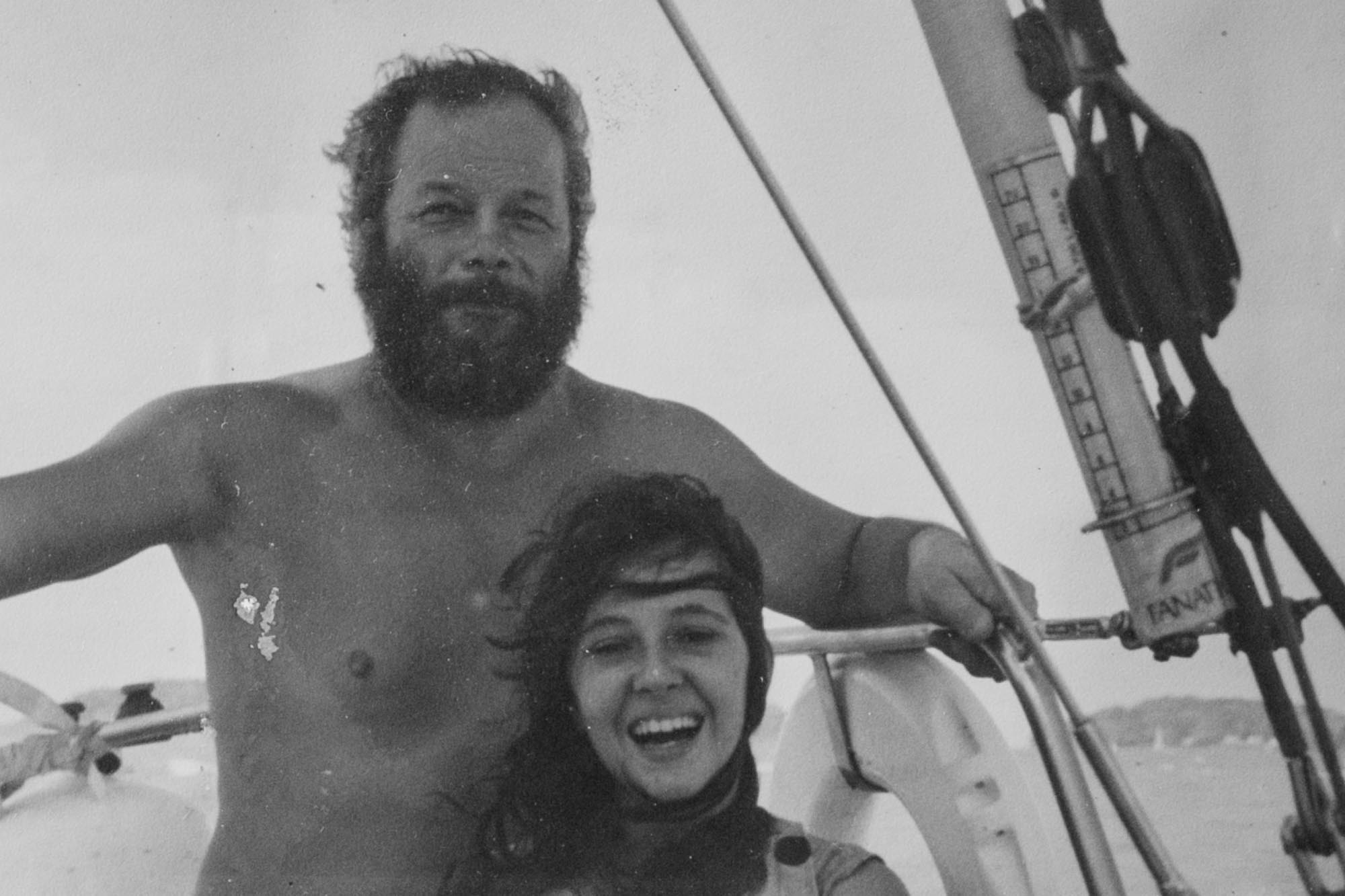

Not only adventure but also love weaves inextricably through his life. “He married Libuna – the best girl from our whole climbing pack. She was always cheerful and friendly… and we even envied him for that,” recalls Václav Hornych in his book Pískaři. Kokša and Libuna stayed close to each other whenever it was possible. They even raised their children sailing the seas.

After more than 50 years of traveling the world, they returned to enjoy their retirement in Czechia. Kokša, however, could not get easily classified within our system: “I’ve got a German passport, French health insurance and permanent residence in Martinique,” he told me at his new address, close to the town of Náchod. His “citizenship” should be changed to: “EARTHLING”.

SECRET ROUTES

When did you tie into the rope for the first time?

Well, it all started with some soloing through the chimneys. Sometimes, I couldn’t believe where I ended up… And then, Venca Hornych goaded me into my first real route: “So you want to start climbing? Show your skills, then.” They tied me in and sent me right into the crack on Skalní koruna tower. And I made it up to the second ring! (It was in 1959, “Stará Cesta” route VIIc/5c+ fr.) I had never used rings before so I had no clue what to do with them. (he laughs) “So guys, who’s gonna climb up here so that we could continue?” I shouted. But everybody was scared of the route and so I stayed alone up there. Imagine – you’re sitting at the ring and you never abseiled before. You have to get out from the sling, wrap the rope around yourself and sit into it. Hohoho!

What about your first “proper” tower?

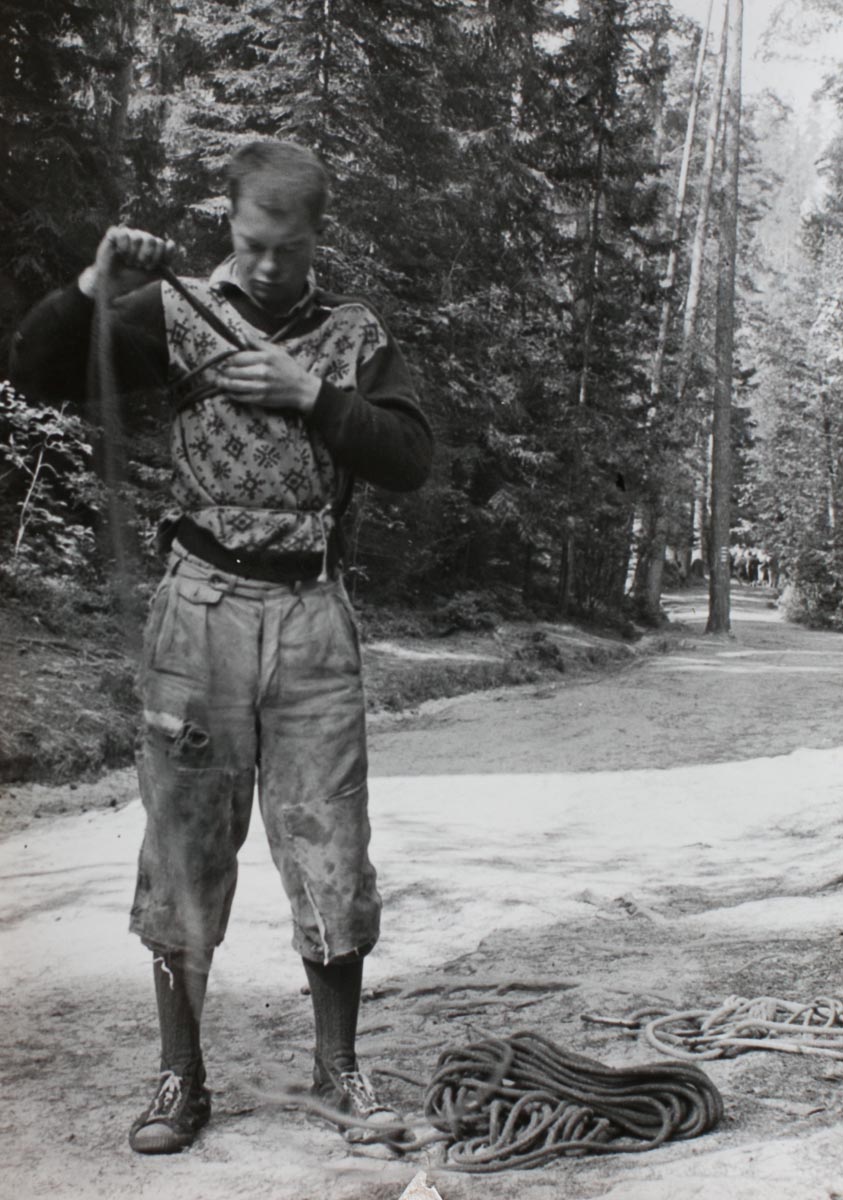

A week later, we went to Adršpach and climbed Starostová. That’s when I finally fell in love with climbing. Then my friend, Jirka Nejezchleba, came with great news: “I’ve got a rope!” It was some sort of a cord used for tethering goats. We used firefighter’s carabiners… In Adršpach, there was a shop where they sold plaited goatskins, which we used for slings. Nejezchleba was 13 years old and we managed to abseil on that sort of material from various towers in Adršpach. It was so feeble that if you pulled on it, it would surely snap.

The very first first ascent?

One of the first ones I recall was on the tower Kat. I never thought it to be a significant route but recently, I have realized that it’s quite a difficult route. (“Krvavá” VIIc/cca 6b+ fr., done in 1960 with Vašek Bruckner.) Then I started climbing with the Bohadlo brothers. We did some hidden and quite mossy first ascents together. We respected the older, local climbers a lot and even avoided them because we thought that it was actually prohibited to climb like that! We always sneaked into the rocks secretly.

Did the guys from Saxony already climb in Adršpach by then?

They arrived a bit later. I remember Herbert Richter – we were almost colleagues. Whenever I made some first ascent that included building human towers, he immediately went there to try if it was possible to freeclimb it. And I climbed his routes as well. I think that I was the first one who repeated his line on the Jitřenka tower. But then I came to know that he hammered a piton during the first ascent which he removed later. And he did the same on Papoušek tower. I climbed it without any pitons, though. The “Parrot crack” was considered to be a real hard and bold line back then. Our friends were sitting all around watching our attempt… The guys from GDR made a route here but the Adršpach climbers managed to send it as well.

So did you see the climbers from Saxony as friends or rivals?

Definitely friends. For instance, I met a guy named Güntner. I knew that there was a possible new line at Křížový Vrch, “Krajková” (VIIIa/6a+ fr.). We started the route together and I let him finish it so that it would technically become his route.

“We thought that it was actually prohibited to climb like that!”

BRUSHWOOD UNDER THE ROUTE

Have you got any favorite routes?

Gilotina tower, “Letecká” … I also remember “Čarovná Stěna” (VIIIa/6a+ fr.). It’s almost impossible for me to forget the moment when you climb out of the chimney with hands on one wall and feet on the other… You can still down climb at that point but once you grab that sidecrack, there’s no way back! Imagine climbing up the sidecrack only to find out that it suddenly ends and turns into a blank wall. Nothing to hold on. Not even a place for a piton… Placing the ringbolt there was really scary. I abseiled from the ring and we finished the route later. When I finally climbed the whole line, I thought: “Who would even climb that? People will get smashed here!” Therefore, Láďa Meier and I added one more ring into the final wall to protect the exposed traverse.

I also remember one more solid route right next to Koberce tower. When I was climbing the final slab, I though: “Nobody is going to repeat this one. They will think that we cheated.” Nowadays, everybody can climb it – the modern climbing shoes just stick… (He probably meant “Mindrák” VIIIa/6a+ at Harfa tower. Kokša usually climbed barefoot or just in ankle-protectors.)

What about the famed “Decháč” VIIIb/6b fr. at Král tower?

We did that one with Jarda Krecbach in an absolutely clean style – what a wonderful route.

“Hrana pádů” VIIIb/6b fr. at Gilotina?

There’s plenty of rings in that one, right? I did that line together with Karel Phillip. The upper wall was quite hard. It took us years to finish this one. It involved two “buildings” – in the second one, you got the leading climber into a position when he still had to one inevitable, hard move. And Karel was quite an elf, so I had to stand on the poor guy’s head (he laughs). (“You weren’t so big as you are today as well,” intervenes Kokša’s wife Libuna jokingly.) I’ve heard that today, people freeclimb it.

Any other memorable lines?

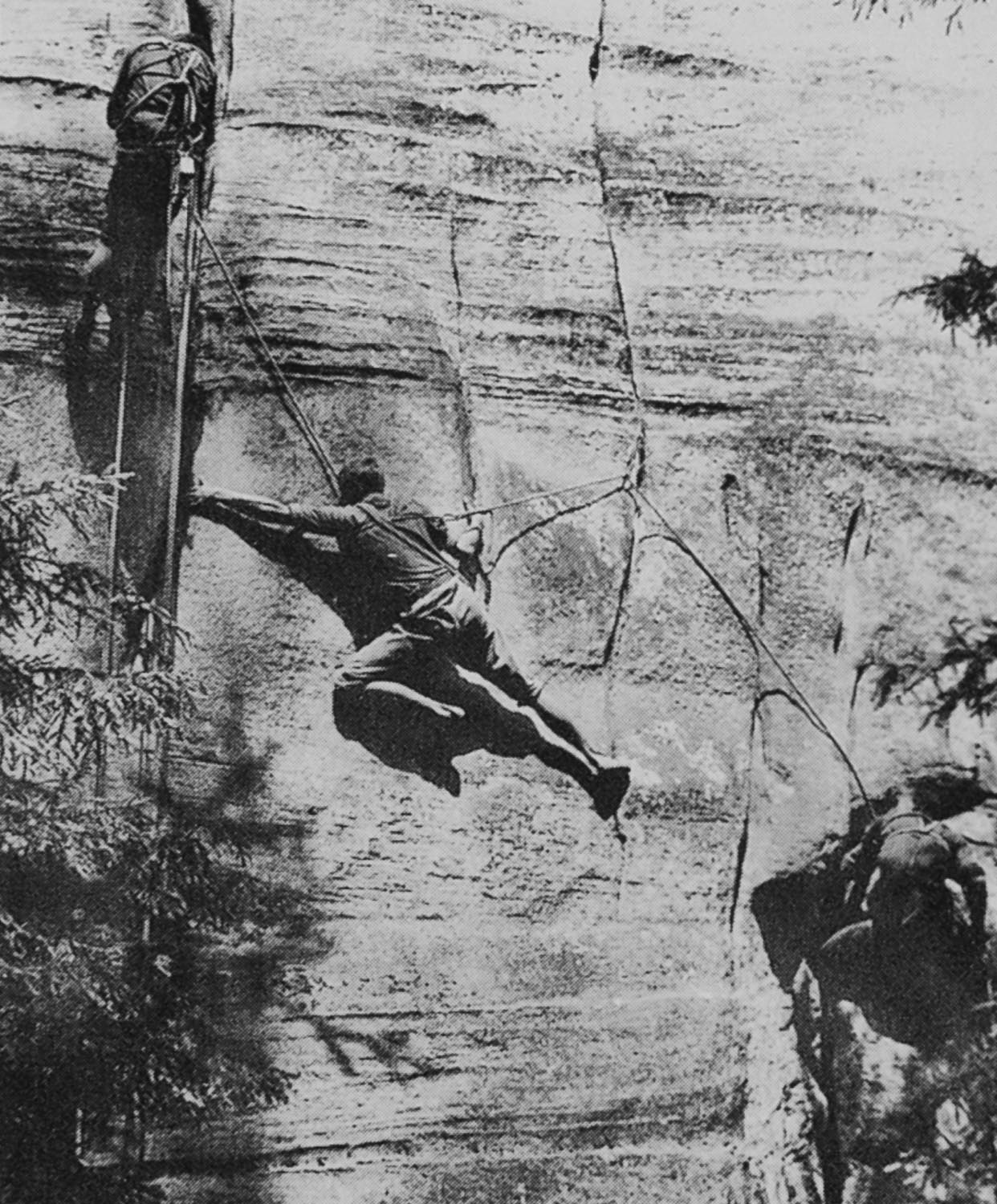

There is a long crack under Milenci tower called “Padák” (VIIc/5c+ fr.). The ring at the end of the crack first seemed quite useless to me… Anyway, I took a whipper on it and flew for about 20 meters. Fortunately, we already had that springy rope from GDR – it was more like a bungee. You fell and it launched you straight back up. When I took that massive whipper, there was a cook from the hotel watching. He literally shat himself when he saw me flying through the branches of the tree. So, there was I, hanging. I realized that I was alive and angrily climbed straight back up there. After all, I decided to place a ring! I remember that on the top of that tower, we found some sculpted emblem – probably done by some German climbers from Dresden.

I also recall the route “Dlouhý Kout” (VIIc/5c+ fr.) at Milenci tower and one more line on Vévoda. The latter one is not hard but long and quite exposed (“Údolní Cesta” VIIb/5c fr.)

The very last route I made was “Cesta Mořských Vlků” (VIIb/5c fr.) – by that time, I already fell in love with the sea, was reading Jack London, dreaming about south seas and imagining Tahitian girls dancing…

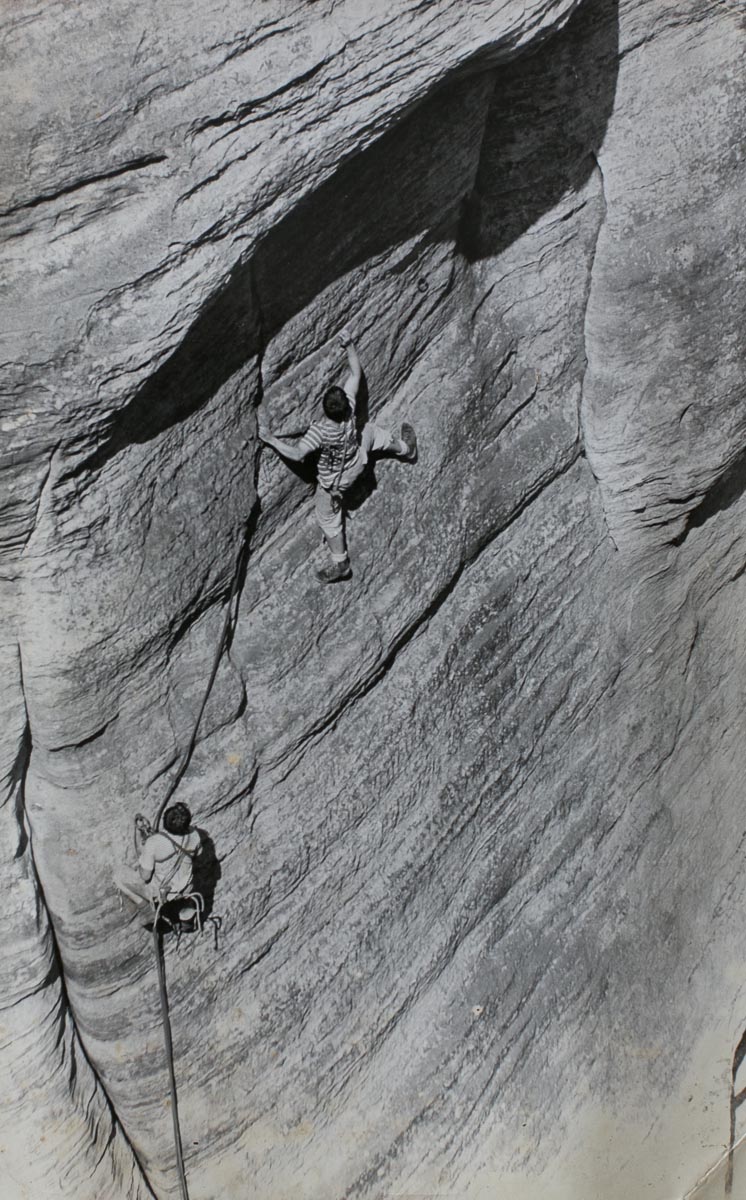

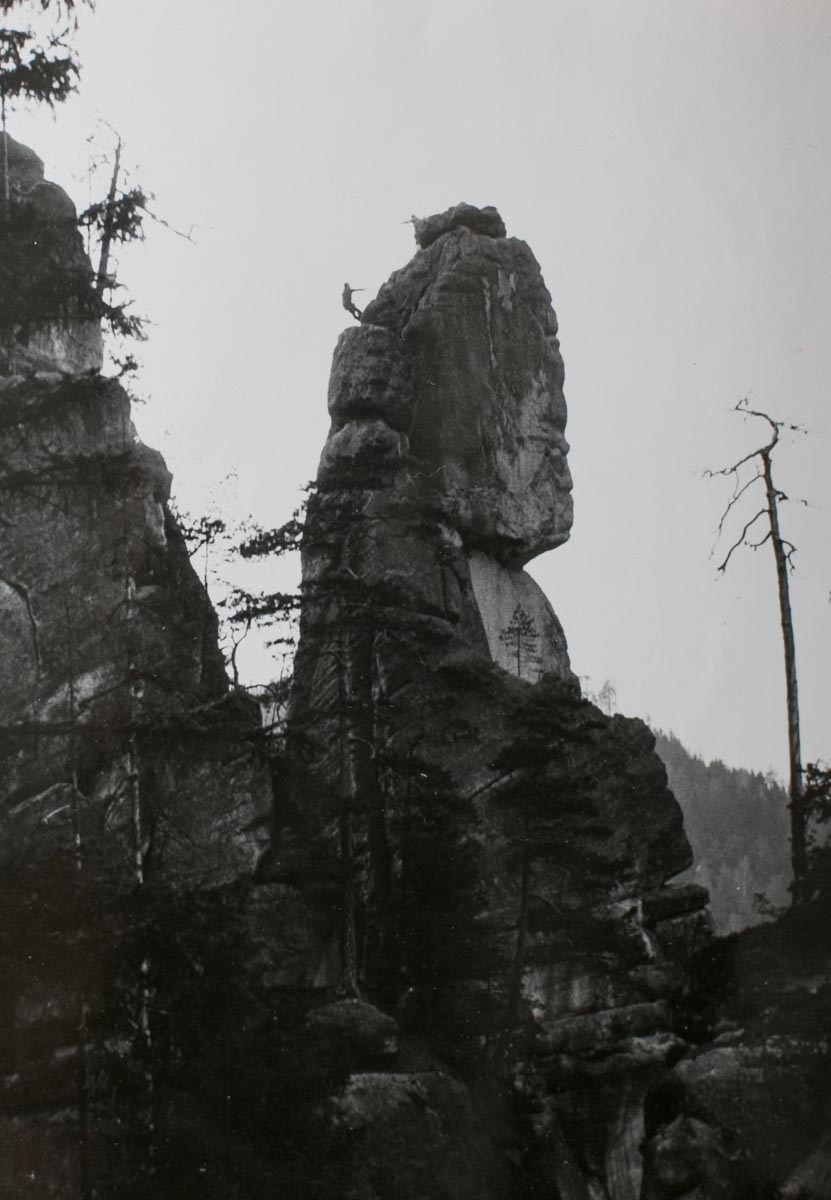

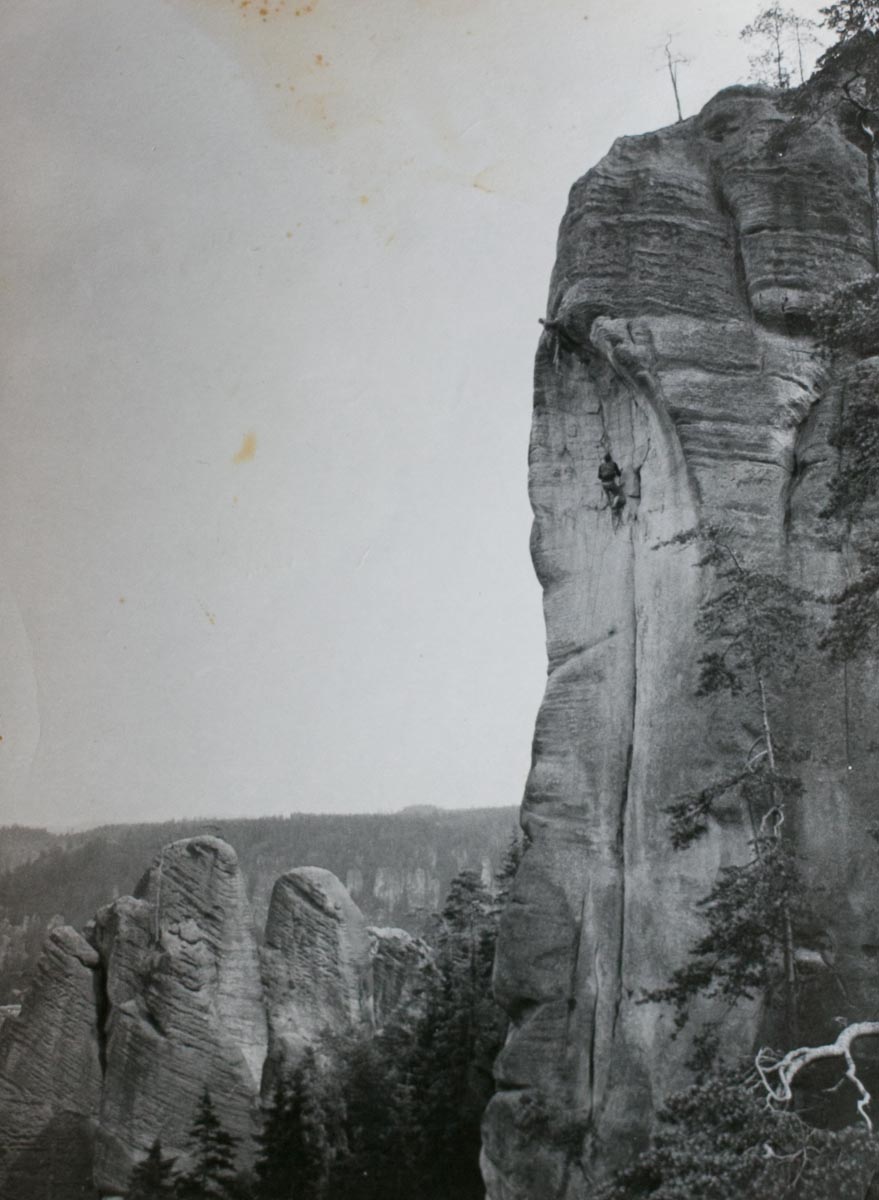

Would you say that your hardest route is “Houbařská Stezka” VIIIb/6b fr. at Zub? (picture below)

I don’t know. That tower impressed me, though. The start of the route is quite hard but I managed to place a bomber fixed sling there. We piled brushwood underneath it up to my chest height to make the landing soft. Nowadays, they use those special pads instead. I don’t even remember how many falls I took before I got past that overhang. The sling always caught me. Later, when I came back with Jára Krecbach, I found out that the sling was missing. Some youngsters from Adršpach wanted to take it, so they chiseled it out with a hammer. Unfortunately, the chipped rock could not hold any sling anymore. Then we placed a ring, from which you traverse all the way to the opening of a long crack. There was a pine and a big chunk of moss at the end of it. How did I get around that? I jammed a block of wood inside a crack and cleaned the crack. But according to the rules for making first ascents on sandstone, you have to place a ring whenever you use the block. Otherwise, I would leave the crack unprotected. I’ve heard that someone fell from the upper part of that crack, though, so I’m glad that the ring saved a life. Then I took a fall close to the top, in the second crack. I placed there a ring and finally finished the route. (he laughs)

Are there any memories from your Adršpach period that you hold dearest?

I guess that would be Libuna here. (he laughs) We even made some first ascent together. We named one of our routes close to Hrad tower “Dagovy Uši” (Dag’s Ears) after our dog. We made it quite casually while picking blueberries. (In the guide, this route is named “Dagova” VI/4c fr. at Velkopoříčská tower.)

Did Libu have to climb with you or did she actually want to?

She was a climber even before we met. She weighed around 40 kg. If she had tried to catch me falling, I would surely drag her through the first ring. I was carrying her all the time so they called me a “cow”.

What about your fellow climbers?

It was a small community. Everybody knew each other. We held the elderly classic climbers in high esteem. (“Well you didn’t like accommodating to others’ plans so you never had a single climbing partner,” comments Libu.) That’s the same with the housework – If I followed your plans, the wood still wouldn’t be chopped. (he laughs)

Was there any first ascent in Adršpach that you planned to do but didn’t manage?

I had had some lines in my mind before I left for Germany. I think that one of them is called “Skalní Modlitba” (“You mean ‘Klenba’ at Zámek tower?” asks Libu.) Yeah, I recommended that line to the boys and Jarda Krecbach with the Meier brothers did it later. Another route that occupied my mind was a long valley wall at Eliška. (Probably “Líbánky” IXa/6c+ done by L. Beneš and F. Čepelka in 1982.) That’s a remarkable wall. A truly modern piece of climbing. Back then, nobody thought that walls like that can be climbed. Or the line on Želva as well – I managed to place one ring into the crack but I didn’t manage to get any further. Somebody finished it later.

Have you ever returned back to Adršpach?

A few times. For instance, soon after I had decided to leave, just after we got married with Libu. Straight from the wedding, we went to climb “Cesta Mořských Vlků” just because it was a great piece of climbing.

CHAMBERMAID IN THE HIGH TATRAS

You did many routes in the Tatras as well.How was that period of your life?

It was quite simple – you came, saw a promising wall and just climbed it. I never registered those routes as well – that was not the point. The only exception was climbing with Zdeněk Studnička, he was a part of the national team back then and had to show them the results. I did not have to justify to anybody. I just climbed what I liked. Some of those routes were hard as well, but my goal wasn’t to get those routes into a guidebook.

Did you go to the Tatras on weekends?

Once, I stayed there for a long time as a chambermaid at Štrbské Pleso. (he laughs) I was changing the sheets and worked as a general servant. In exchange for that, we could live in the nice and warm attic – trust me, that was way better than any bivouac. In the morning, we just grabbed some food at the breakfast buffet and went climbing.

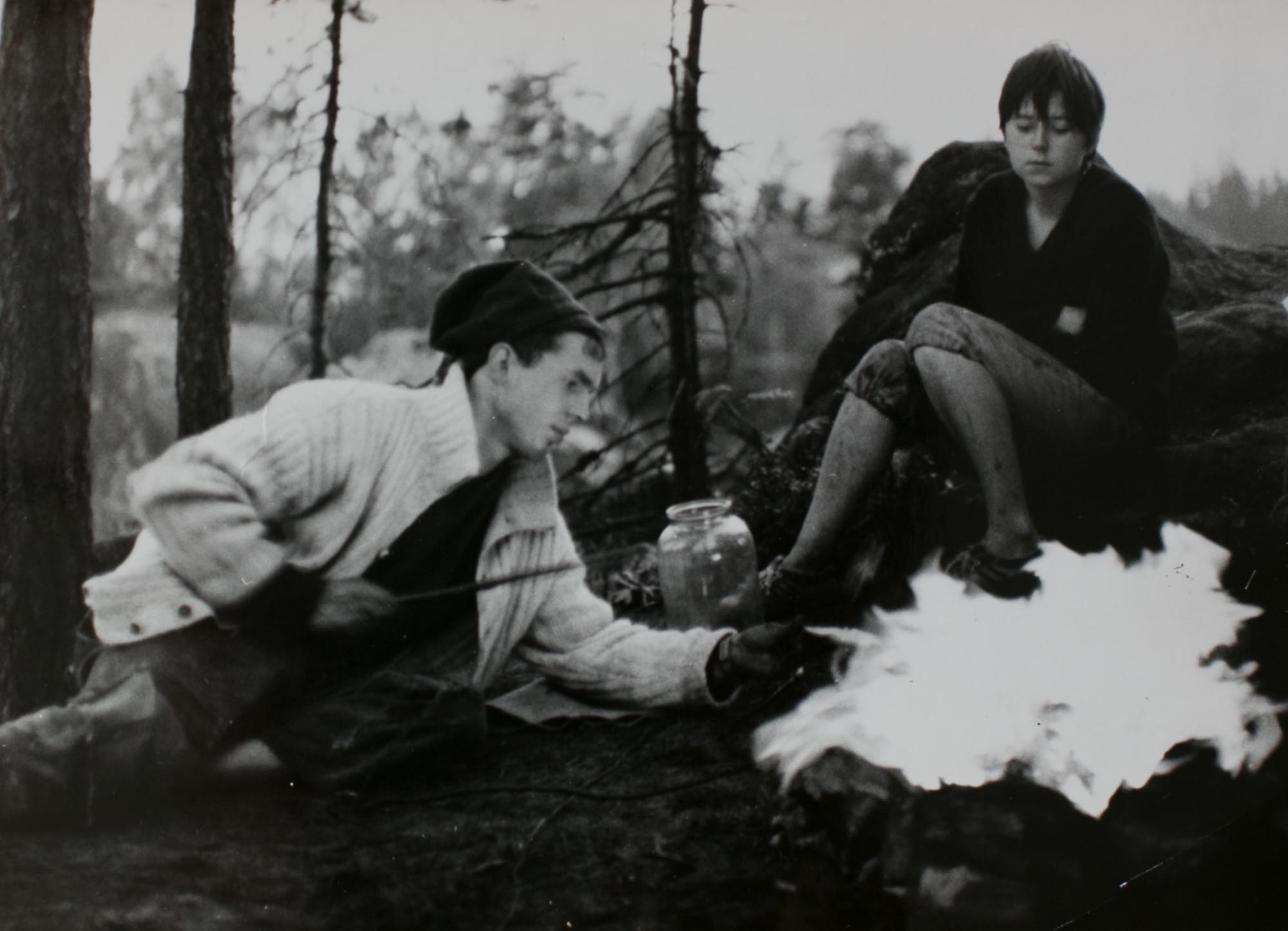

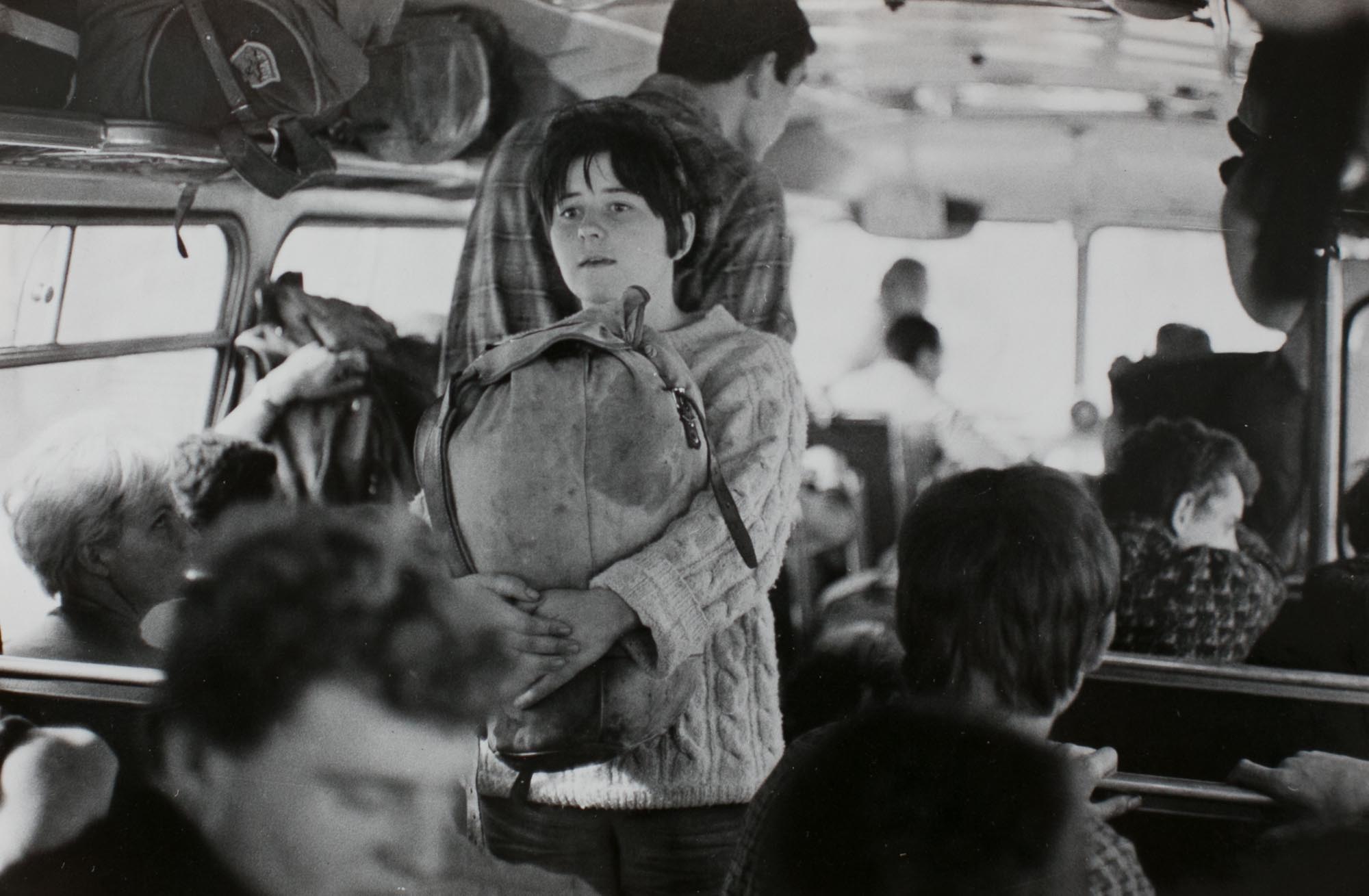

May 1965, as Honza “Jenny” Farkaš remembers it.

That was quite a party. Loads of booze and singing all night. Imagine, Kokša almost shot his wife-to-be Libuna. After WWII, you could find a gun in almost every other attic in Adršpach. Today, it’s long gone, so we can talk about it. We used to drink quite a lot but Kokša, fortunately, not so much. It was already late and suddenly two guys arrived at the party. One of them was quite drunk, had a loaded gun and started shooting just for the fun of it.

Bang! One window. Bang! Another. Kokša got angry and disarmed him. He went behind the hut and wanted to empty the barrel into a wooden wall. Fortunately, he first shouted: “Is there anyone inside?” “Yeah, that’s me,” answered Libu from inside the outhouse. He waited until she left. Shot the gun empty and returned it. That was quite close. The following day, the old classics including Láďa Škroupků came: “What happened? How come the windows are shot out?” “Sorry guys, we accidentally shot them with a bow,” we kept denying. Somehow, we convinced them, otherwise, the police would have to investigate it. I was never into guns – knives and sabers were my thing. (photo: former Náchodská hut)

DANCE IN THE VALAIS

Why did you decide to leave your home in the ’60s?

Climbing brought me to the west. The Alps and so on… We did some nice walls together with Peter Haag, for example the north face of Matterhorn. With this climb, we celebrated 100th anniversary of the first ascent of the Matterhorn, so that was quite splendid. There were two Japanese guys stuck in the wall as well and we managed to get them out. Otherwise, they would have been stuck there. Back then, there were no phones – you just went for it and had to rely on yourself.

How did you meet Peter?

Well, when I emigrated, I arrived in Germany in the city of Reutlingen, where my aunt lived… There was a limestone climbing area Schwäbische Alb nearby. I was surprised by how nice routes were there. Back then, you could not easily find all the info on the internet. Officially, I was an immigrant, and this is exactly how I felt.

Did you start climbing in the mountains later?

Exactly. I met Peter, and we went to Munich to buy all the climbing equipment – ice axes, crampons… And then we hitchhiked to Switzerland where we climbed several walls including Lenzpitze (4 294 m. a. s. l.). It took me ages to get acclimatized to the high altitude.

From Saas Fee, we went to Zermatt to climb the famed Matterhorn. “If we must go there, we should at least do a new route,” I was trying to convince Peter. But the weather was lousy and we had to wait for quite long and then we managed to climb only the classic. I tell you, that’s one crappy route. It’s falling apart! You don’t even have to belay – there is nowhere you could build an anchor. And it’s hard as well.

When we came down to Zermatt, a carriage picked us up and brought us to the Zermatt Hof Hotel (Kokša does a farting sound with his lips.) I even got to dance with the young countess of Wallis. (he laughs) Then we went to Chamonix and climbed the north face of Aiguilles du Midi (3 842 m a. s. l.) together with another climber. We were ascending through a couloir that resembled a shooting range – there were stones swooshing all around us. The guy who joined us got hit by one of those stones right into a knee. That was no joke. We had to abseil and drag him to the bivouac to the other friends. Most people would just turn around but Peter and I were quite crazy – on the following day, we went for it again and managed to climb it in an amazing time, around 11 hours. (Probably “Frendo Spur” route, 1200 m, III, usually climbed in 1–2 days.)

Anyway, that shooting range left quite an impression… I told myself: “Shit, you just stand there waiting for one of those stones to hit you.” That experience made me change my approach to climbing in the mountains. It just planted a seed of doubt…

Our next plan was to do “Direttissima” on Eiger. Soon, there was plenty of others who wanted to join us. There were even some rival groups. Some guys started in the winter and got stuck in the wall for three weeks. I was exchanging letters with Libu who was still in Czechoslovakia by then: “Should I go there, or should I stay?” I was hesitating. Anyway, I never liked huge groups of people and that was exactly how these expeditions looked like back then. Hauling tons of material up and down, chiseling bivouacs into ice, building ropeways… It was not an easy decision but finally, I decided to scratch it.

How did that expedition turn out?

One of my friends got out with serious frostbites – they had to cut his fingers off… And that American, John Harlin, fell to death (1966). How did it happen? There were stones falling down and one cut the rope on which he was jumaring. So, this is how I ended my climbing career – I didn’t even go to see the Eiger – I just phoned my friends from home.

You never climbed since then?

Never. You cannot do two things at once – by that time, I was already interested in ships and sailing. Maybe I went climbing on some local crags a few times but I couldn’t do any dynamic moves anymore. “Help me a bit,” I shouted to the belayer in the moves that were automatic before. As I said, I already fell in love with the sea and water.

TO GET LOST IN THE SEA

Libu says that you had been one of the best freedivers. How long could you stay under the surface and hold your breath?

Not too long lately. I never timed my records but sometimes, I was quite surprised with how I forgot that one needs to breathe from time to time… We used to eat only what we could find in the sea. There’s plenty of things but you need to know the species – after 40 years on the sea, you become a sort of biologist. Diving has always been my passion. I loved it already when I lived here in Czechoslovakia. We used to dive at a local pond.

How does fishing while freediving looks like?

When you’re fishing in the Caribbean, there is a plateau around each of the islands around 25 meters under the surface. You swim to the bottom and find a rock to hold on to… Of course, you need to bring a weight to keep you down there – I needed 11 kilos to get to the depth of around 30 meters. And you wait… The fish is curious and it slowly approaches to inspect you. It never goes too close, though, it’s clever. Then you slowly follow it, silently, like a predator. You track her on and on and you say to yourself: “Damn it, I need to go up sometime soon.” (he laughs)

How do you kill it?

With a harpoon. You need to have a good harpoon, though, no garbage. I had a good job in Martinique so I kept eyeing a nice harpoon in a local store… One day, I finally bought it – it cost me 500 euros. But after all, I just hung it on a wall in the cabin and never used it. Just admired it. Then I gave it to my son.

What’s your favorite food?

I really like cabbage. I also loved Polynesian cuisine – they use coconut milk a lot. I brought the fish, and Libu grated the coconut in the same way we grated potatoes back home. Then you wrap that in a cloth and squeeze coconut cream out of it… It’s a real treat. But I should not eat too much of it. This is how they ate in the old times. Recently, the locals started eating like Europeans and got really fat because of that.

„The fish is curious and it slowly approaches to inspect you. It never goes too close, though, it’s clever.“

Did you start sailing right away with Libu or did she join you later?

It was a bit complicated. We got married in Czechoslovakia so that Libu could follow me to Germany. But the communists wouldn’t allow her to leave the country sooner than a year after the wedding. Libuna’s mother got angry, even wrote a letter to the president himself and threatened the communists so much that they eventually allowed Libuna to leave a bit earlier.

What was your first ship?

I think I bought it in 1966. It was a small ship, about 7 meters long. It was enough to show us the whole world of sailing, though. One day, a captain from a large and amazing ship asked us: “Would you like to join our crew?” They needed sailors, so we joined them. That was in Cannes, at the marina Port Pierre Canto.

How long did you stay in France?

About two seasons. Then we met a guy who offered us a skipper position (independent captain for hire) on his 20-meter ship. He wanted to send the boat to Dakar to hunt for shark’s fins. He even offered us more money than we could get working as artisans in Germany. Later, we met two German brothers who managed to build a ship on their own. “If they can do it, we can,” I thought to myself. So I started drawing plans for my new ship – I had a whole wall full of plans and drawings. Then, when we got out of water for some time, I started building it in our garden. We named it Rosinante after the horse of Don Quixote (he fought against windmills as well).

HOBOS

Did you already know that you were about to leave the dry land and your home for quite some time?

There was not much that drew me back home anymore.

How did you communicate with the rest of your family in the Czech Republic?

The world was different back then – nowadays, the young generation can hardly imagine it. When you wanted to phone somebody, you needed to go to the post office and all the calls were monitored and “censored”.

First, we had a permanent residence in Germany but then we deregistered and technically became missing. We turned to hobos. Our last passports were from Trinidad. After Germany united, we wanted to get our passports in Panama but the officers from the embassy told us: “You cannot have a permanent residence on a ship.” They just wrote: “Ohne festen Wohnsitz.” (without a permanent residence) We lived like that for about 10 years. Nobody reads it anyway. Later, in Guyana, where we spent three years, the officers wanted us to get some permanent address so that we could get paid for work.

Can you tell us how did the ship navigation work back then?

Navigation was an issue. You had to use a sextant and compass. There was nothing like phones and GPS. Navigation skills were held in high esteem. You had to spend some time learning them. The position of the Sun was the most important factor back then.

How did you get to your first sailing across the Atlantic Ocean?

Once, we went with the kids and Libu to Barcelona where I met a guy who had an amazing old ship. Then some Frenchmen arrived on a nearly-wrecked ship: “We’re on our way to the Caribbean,” they said and I couldn’t believe them. “If they can go with such a wreck to the Caribbean, we can do it as well!” But the question was if we should go with the old ship of the friend or with our Rosinante. Then the guy says: “Look, this ship is such an old-timer that it deserves the journey.” So, we did not hesitate for a single moment and joined him.

„If they can go with such a wreck to the Caribbean, we can do it as well!“

SAILING THE OCEAN WITH THE KIDS

What happened next?

We took all our 800 German Marks, some cans, and off we went. We started with the Canary Islands and then went straight for the west. It’s not so much of a big deal – by then, my navigation skills with sextant got probably a bit better. You have to own a precise chronometer. If you miss the exact time by just a single second, you’ll end up 60 miles from your destination. In the ’70s, you could get your hands on the first electronic clocks/tempomats and those were already quite precise. The technology made navigation much easier.

Later Libu and I got into the business of bringing ships to Europe for people who were too scared of that trip. Anybody with a piece of wood can get to the Caribbean – it’s a piece of cake. But to get back is much more difficult. “Can you get our ship to Mallorca?” Asked less experienced shipowners. And this is how Libu became an admiral and I a captain.

Did you bring your children on these voyages?

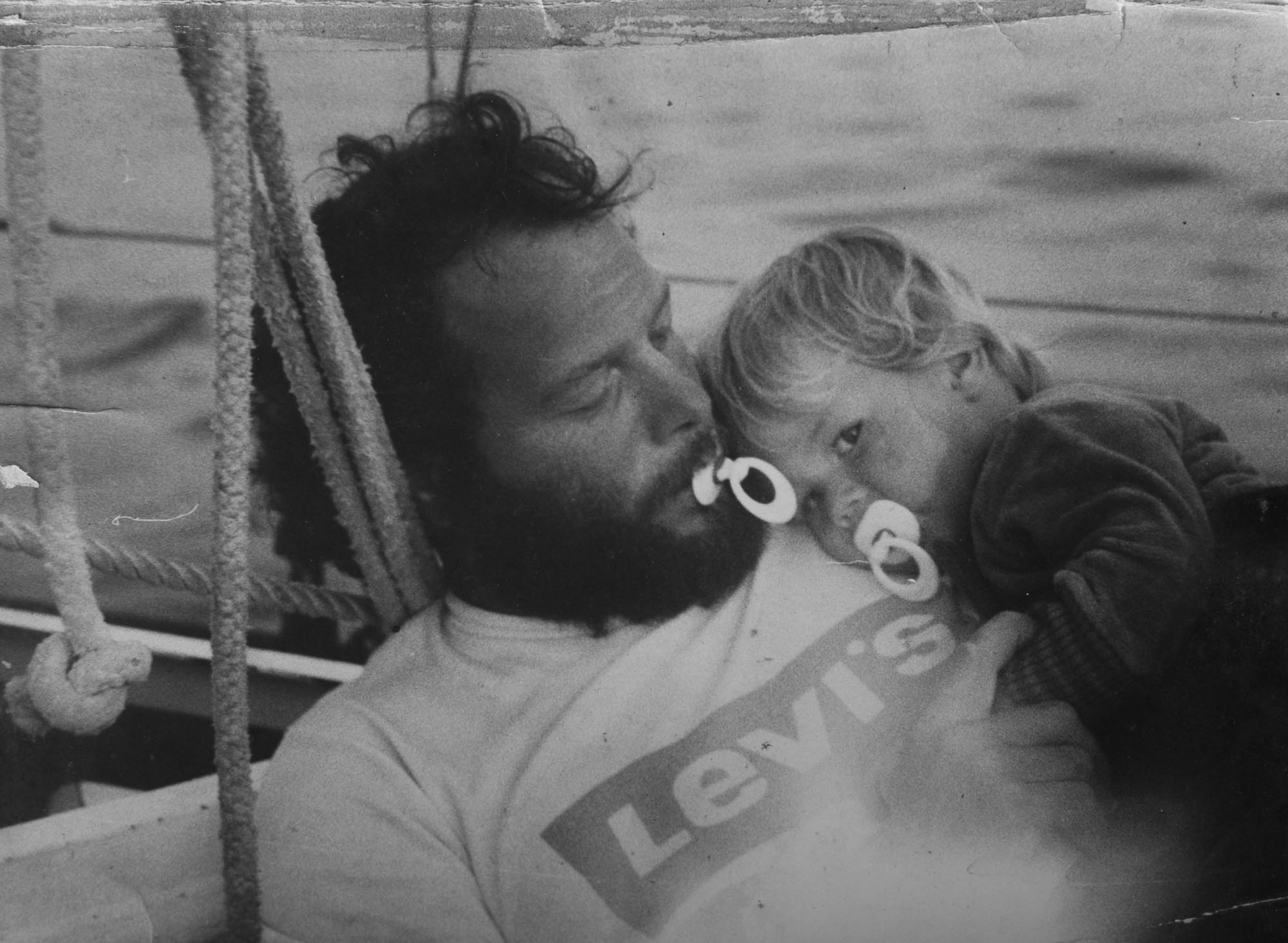

Yes. Together, we sailed across the Atlantic several times. Karin was born in 1970 and Kája a few years later.

How did your children manage to study while sailing?

They did well. We taught them different subjects, helped them with essays, but we never overdid it. As we arrived in Brazil, Karin turned 18 and wanted to get back to school – so we bought her a flight ticket and off she went. Kája always did distance learning and he did very well. When he was 18, he sailed across the Atlantic, alone. Both of them have learned to speak French and Spanish very well.

KOKŠA’S COMEBACK TO ADRŠPACH

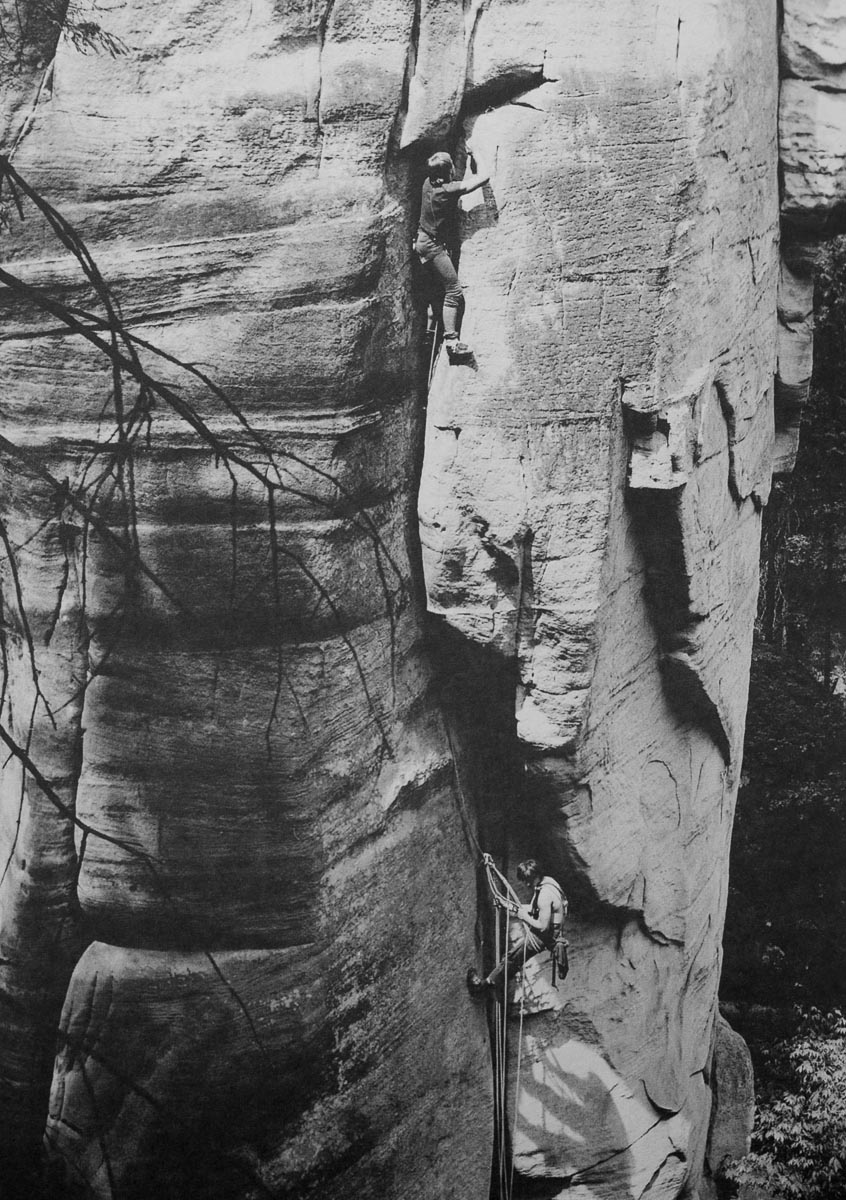

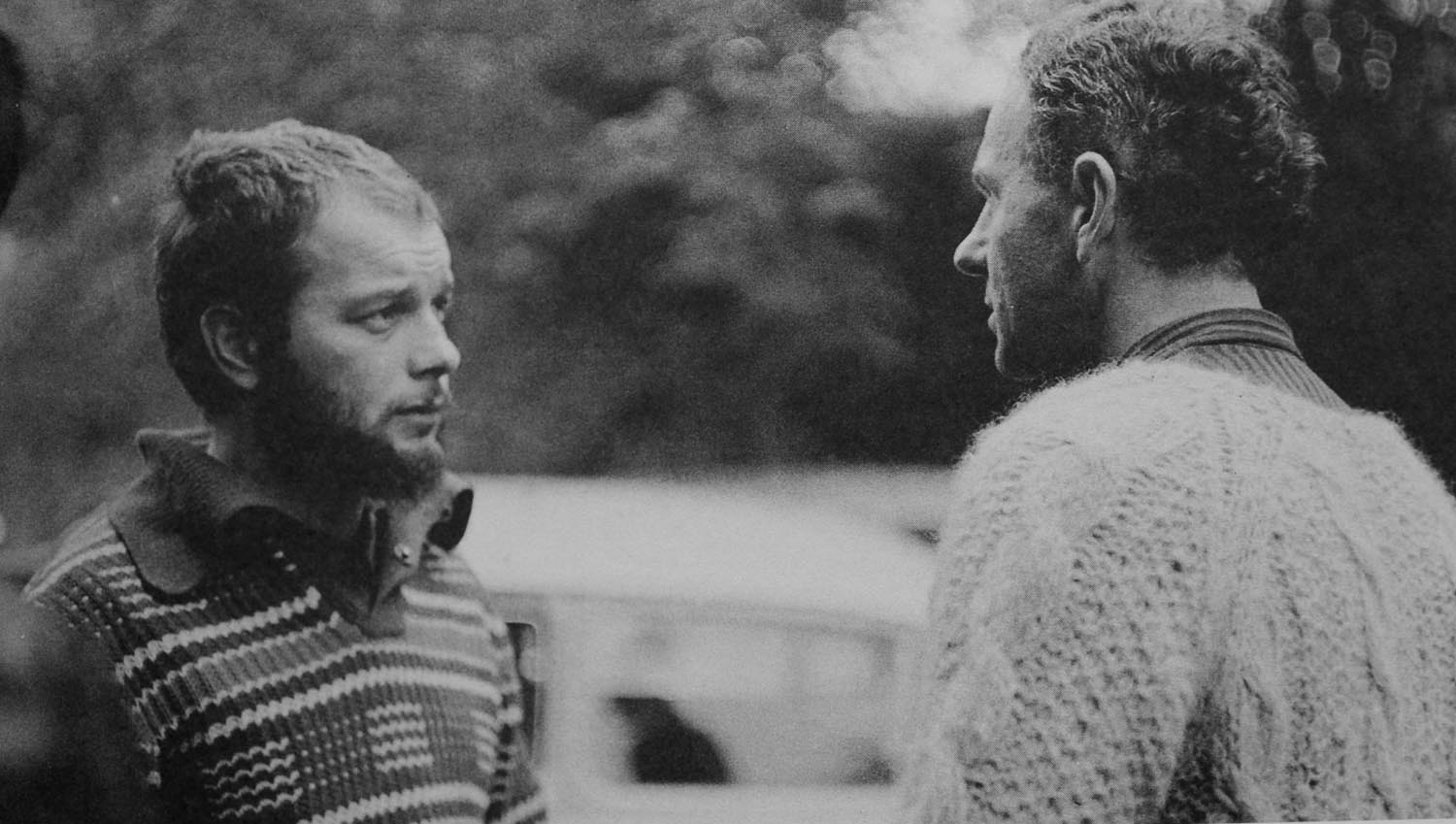

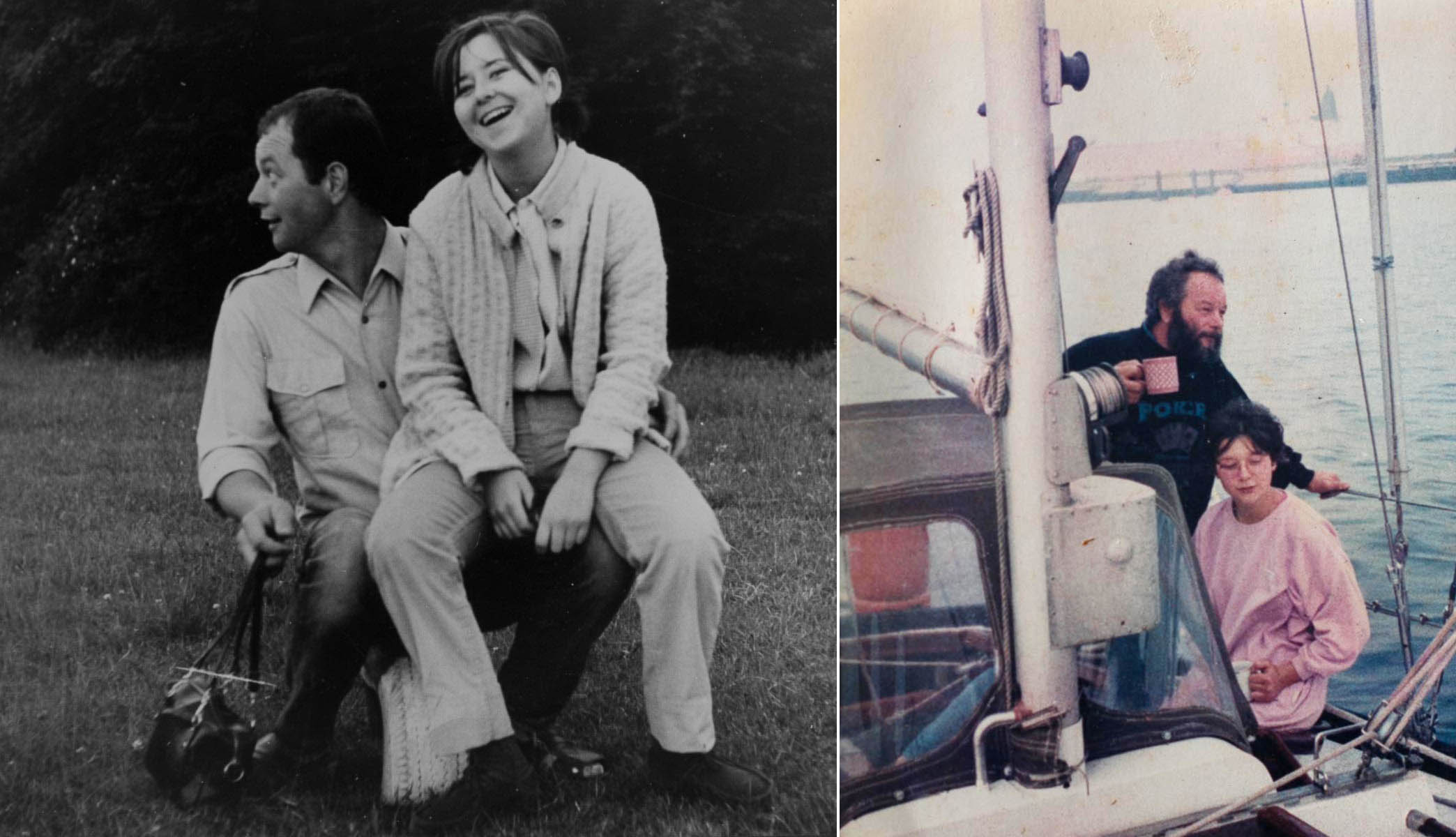

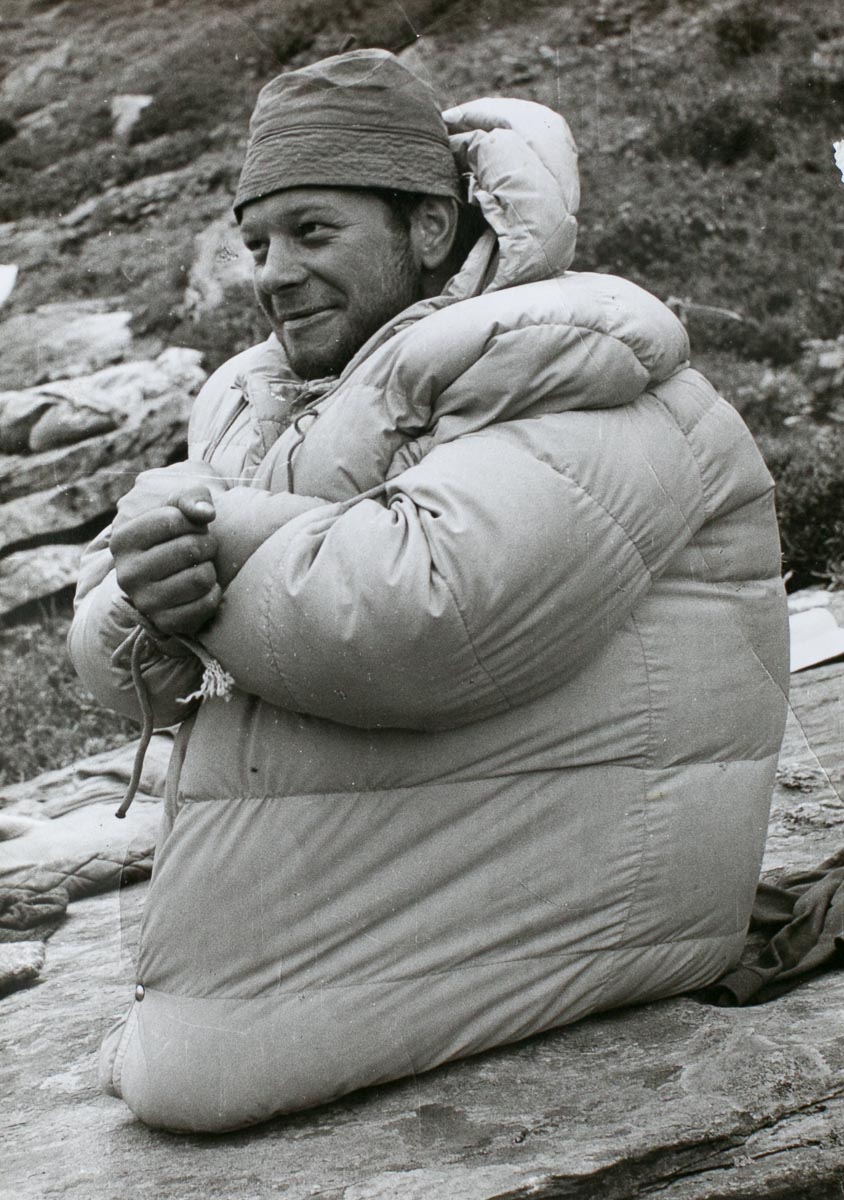

Pavel Lisák recalls the winter of 1981 (in the picture)

It was 1981 and Tomáš Čada and I went for a walk into the rocks. Then we found ourselves at the Starozámecký Vrch hill where we met two people. A man with a woman. “Hi,” we greeted them and admired the landscape. “Are you guys climbers?” asked the man. “Yeah, we are,” we answered. “And how do you like climbing in the Himalayas area?” And we said: “We sure like that one!” And the guy says: “Well, I discovered it.” And then we wondered – Tomáš was around 18 and I was 19. Who on earth could that be? After a while, it dawned on us: “Kokša!” We took him to the Tošovák climber’s pub where he met his old friends.

It was actually his first visit to Adršpach since he left for Germany. Nobody knew anything about him and we could not recognize him by his looks. He was an important figure even for us who had never seen him before. And he still is. We were so grateful to meet him!

TWO WEEKS IN A SHELL

When sailing, did you ever feel like during that first ascent, when you knew that there was no way back?That you were no longer in control?

I think that you’re safer on the ship than on a rock. It’s a sort of a snail’s shell. When the weather’s too bad, you cannot do anything outside anyway. The wind’s just too strong – you cannot fight it. When a hurricane hits you, you can only drop all of your sails, tie the helm and crawl into your shell to wait until it ends. You have to think in advance and act before it comes. And the ship it’s such a fantastic thing – it can make it through it. When the wind is persistent, it’s just constantly tilted at 45 degrees. All the time. You need to tie all the things inside the ship… We made it through five solid hurricanes.

Were you afraid at any time?

Sure – in the Indian ocean. We departed from Cocos Keeling island already in bad weather conditions and we wanted to continue to Chagos which is further west. On the radio, however, we heard that the weather there is just awful. “Let’s turn it around,” we decided and changed our course for Mauricius where our friends were sailing as well. But strong winds and huge waves caught us on our way. It lasted for around two weeks, we could use only the tiniest sails and could not get out of the cabin. After the weather got a bit better, we finally got out on the deck. We sat and chatted, and suddenly: Booom! We could see a huge fin, and there was a large pool of blood on the stern. A whale hit us from below and probably got injured by the keel. But then we checked it and it wasn’t damaged at all. Strange.

What was the bigger adventure – building Rosinante or steering it?

I was always surprised by how capable that ship was. It’s a big difference if you build a regatta (race ship) or a ship to live in. We call those modern ships “yoghurt tubs”. You hit the slightest shoal and it cracks. Or you hit a stone with your keel, it snaps, and you sink. When we crashed into the whale, that was quite a hit. A modern ship would probably sink, but ours made it… And when I say that we build it with our own hands, I mean every single piece of it. We even sewed our own sails.

Are there any climbing skills you have used during sailing?

Well, you work with ropes all the time. Knowing how to build scaffolding can be useful as well. I can still do it – come check (he laughs and shows me his terrace that he’s just repairing.)

In French Guiana, you worked with astronauts – what exactly did you do there?

A technician. Various tubing and industrial installation. I helped them to build a launching pad (for the European Space Agency). That why we got stuck there for so long. If we stayed and retired in Guiana, it would be much easier than here in the Czech Republic.

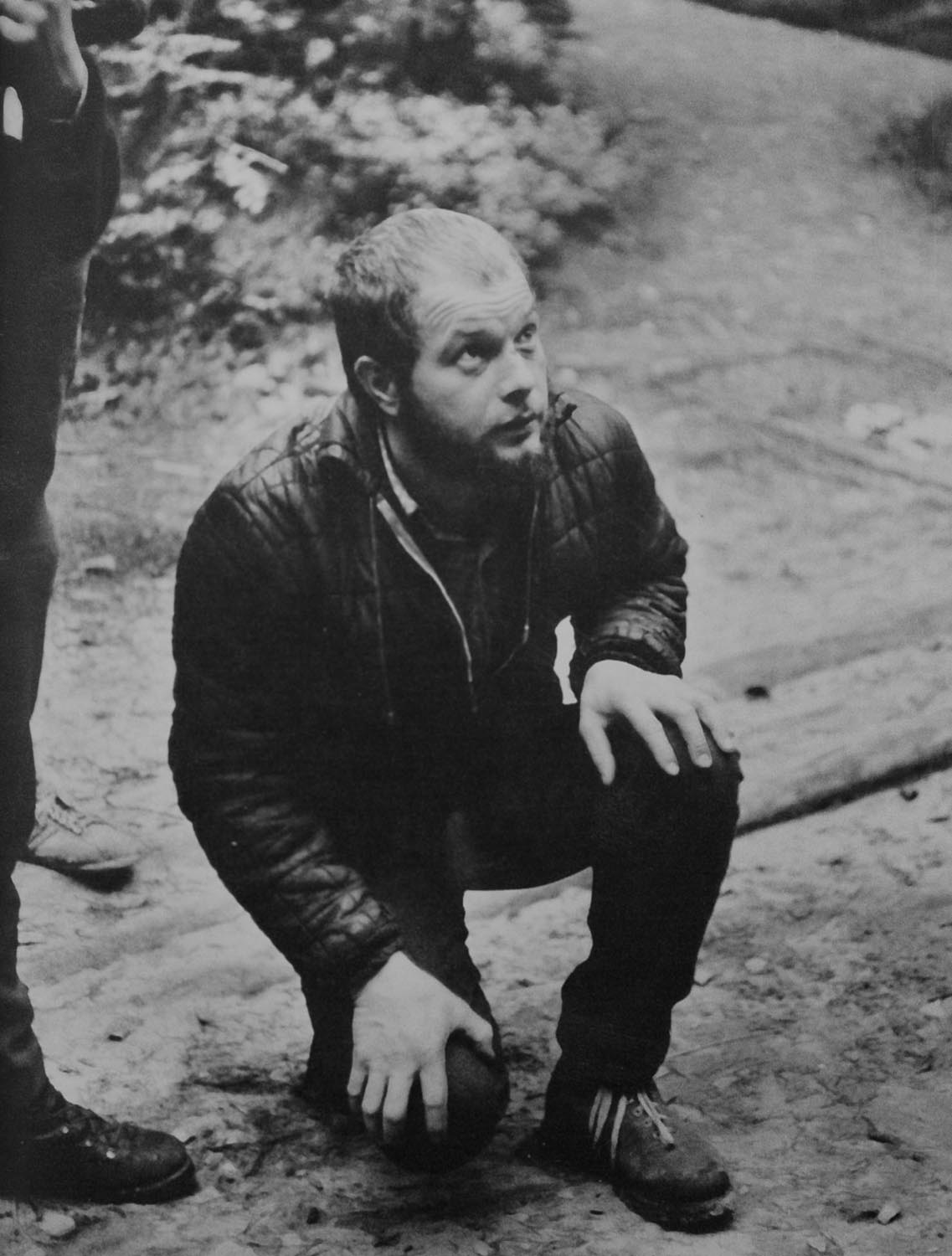

October 2017 as Pavel Roubal (in the picture) remembers it

I just arrived at Martinique after a solo race across the Atlantic. Some guy came and started speaking Czech: “Hi! You’re Czech as well? Come and join us for a lunch.” So he picked me up and we went to his ship. Then I realized it was Kokša who had lived this life together with his wife for quite some time!

It was quite absurd – I just finished the race of my life and was still partly hallucinating. But meeting Kokša was a wholly different level. I still had soaked, salty hands… And there is Kokša, showing his old climbing guidebook with hand-drawn lines talking about the rings he placed, slings he torn, and how to climb those routes… When he started talking about climbing in Ádr, my hands started sweating on top of that all…

I had never met him before – for me, he had been this fabled figure from the guidebooks. I remember that there was a list of routes in Adršpach that you cannot miss – half of them was done by Kokša. All the sailors that lived in the same bay as Kokša used small motorboats to get from their ships to the mainland. Not Kokša, though – he was angry with all the noise so he built a small sailboat. Once you see him, you realize that he’s just different.

BACK HOME

Is the sea changing lately?

The whole yachting business changed. It’s the same as with climbing. More and more ships and companies that rent them. Sailing culture was entirely different in the ’70s. First and foremost – the life under the surface disappeared – it used to be a paradise… and now? You find just a few pieces of plastic lying down there. Most of the sailors used to get around by ships – today, they fly all the way to the harbour and rent the boat with a captain. You met different kinds of people there – adventurers. Whenever you anchored a boat, you went out to greet your neighbours. Sailing used to be a social thing. Today, people just use those boats as their private camping places. They’re not sailors, but whatever happens, they can call help via iridium (a satellite telephone).

How much did Czech Republic/Europe change in all those years?

It definitely changed for the better. (“You should ask me, Kokša doesn’t go anywhere,” says Libu.) You can buy whatever you want anytime you want it. Or when you need a bag of cement, you just drive down the city and simply get it in no time. Well, when I’m talking about it – come and see the pile of wood that the friends from Adršpach helped me to chop…

What was it that lured you back to the Czech Republic?

Well, we’re not the youngest anymore and we’ve always planned to “return home when the right time comes.” Maybe we just went a bit sooner than we should.

He was born in 1940 near Náchod in Kladsko (That area was part of Germany back then, today it’s Polish.)

He was trained to be a tinsmith and roofer.

His first ascents that he made during his six-years-long climbing career are part of Adršpach’s top routes. (“Letecká” at Milenci, “Houbařská” at Zub, “Hrana Pádů” at Gilotina…)

He married Libuna in 1966 and has two children with her – Kája is currently sailing the seas nearby the Cayman Islands and Karin lives in Germany.

He built his own sailboat Rosinante, with which he sailed oceans for about 50 years.

He says that next year, he plans to dive into beekeeping.

.

__________